Speaking Your Truth Through Slam Poetry: A Unit Overview

“We’re doing poetry? I haaaaaaate poetry! It’s SO boring, Mr. Anderson!”

One of the easiest ways to make a room full of middle schoolers groan is to say the word “poetry.” I don’t blame them. The thought of analyzing the theme of “Hope is the Thing with Feathers” or any of the other nature themed poems that regularly pop up on standardized tests makes my eyes slide back inside my head.

A few years ago I began teaching a unit on slam poetry. Students responded immediately to slam poetry’s relevance, topics, and overall style. Slam poetry feels vibrant and current. And thanks to the internet, teachers now have access to cutting edge slam poetry written by people that look and sound like their adolescent students. I’ve taught this unit three years in a row, and it never fails to produce some of my students’ strongest writing of the year.

What follows is my basic blueprint for my annual slam poetry unit. This unit combines “just right” mentor texts with rock solid instructional activities. Because it requires students to be vulnerable, I typically save the unit for the back half of the school year. That way I’ve had time to build and sustain a sense of classroom community with students. Without vulnerability, slam poetry is nothing.

Unit Title: Speaking Your Truth through Slam Poetry

Time Length: Five weeks of 42 minute class periods

Final Product: Students will write, revise, and submit an original slam poem. While students do not have to present, they are encouraged.

Standards: These are from Virginia. I’m sure most states/Common Core have something similar.

- describe the impact of word choice, imagery, and literary devices on different poems (7.5d)

- analyze the themes of various poems (7.5a)

- write, revise, and edit original poetry that that incorporates word choice, imagery, and literary devices (7.7d, g, j)

Mentor Texts: Ten years of teaching English Language Arts has taught me that providing students with engaging, developmentally appropriate, and culturally responsive mentor texts from the “real world” is the most essential component of a successful unit. To that end, I’ve collected every slam poem I’ve ever used into a mentor text packet for you to make a copy of. Every poem in this mentor text packet has a corresponding YouTube video of the poet delivering (or ‘slamming’) their poem.

Content Warning: If you plan on using these poems, make sure you read through them first. For some of the poems I give a content warning and provide students with a chance to sneak out first. The poems here deal with topics such as: anxiety, depression, grief, ADHD, race, gender, substance abuse, technology, and religion.

Basic Instructional Sequence: The basic instructional sequence for this unit is adapted from the mentor text model described by Katie Wood Ray in Study Driven. Students begin by “immersing” themselves in slam poems. They listen, discuss, read, and write. The next step asks students to “write under the influence” of the mentor texts. Finally, students use specific texts and techniques to revise and deliver their poems.

Immersion Phase: Expose to students to the mentor texts. Get them reading, writing, and talking about them.

- Introduce the genre with a high interest slam poem (You can never go wrong with Touchscreen). Help students identify the difference between first and second draft reading. The former helps students access the content (the WHAT of the poem) while the latter gives students a way to analyze the craft moves made by the poet (the HOW of the poem).

- Introduce one poem a day to students. Watch them multiple times. Read them multiple times. Give students room to respond to the poems in a way that suits them. This is where I introduce “punctuation annotations.” Students read through the poems and mark up the lines with hearts, exclamation marks, question marks, etc. What surprises them? What lines can they identify with? Etc.

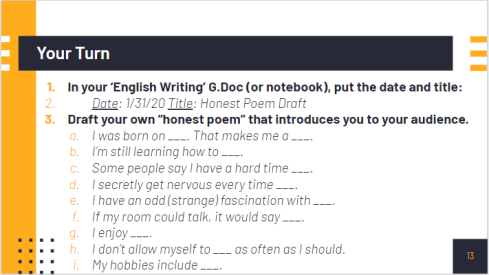

- Then, have students use the basic framework of the day’s poem to generate their own version. The goal here is to give students their own bank of writing to draw from when it comes time to commit to a draft. I always give students two options. They can just “go for it” and write something with the mentor poem on top of their brain. Or they can use a “poem frame,” a more sophisticated fill-in-the-blanks. This requires the teacher to use a poem with an easily identifiable and copyable format. Below is one of the slides I used from the excellent Honest Poem by Rudy Francisco. The bullet points on the slide come from lines in the poem that I adapted.

- Students end this phase filling out a simple “What is slam poetry?” handout. It has four basic questions about what slam poetry is, how it’s different from more traditional forms of poetry, and what they can write about for their own poems. Students have immersed themselves in slam poetry for about a week at this point, so there isn’t much scaffolding or direct instruction that happens here.

Writing under the influence: Students use the mentor texts as guides to help them write their own poems.

- The goal of this short phase is for students to complete their “down draft.” To just get something “down” on the paper. We’ll fix it “up” in the next phase.

- Students are encouraged to “talk back” to any ideas or stereotypes others might have about them. I typically introduce this idea by asking students to tell me what they assume about teachers. That we have no lives. That we live at school. That we hate kids. You can spend as much/little time with this as you want.

- Students can use any of their poem quick writes from the previous classes.

- Students can practice “lifting a line,” a simple technique where students pick a favorite line from a poem and use that to either begin or end their own original poem.

- I try to help them focus on quantity instead of quality at this stage. I shout “JUST WRITE!” a lot during this time.

Using Mentor Texts to Revise and Polish: This is where the real work comes in! Now that most students have a workable draft, it’s time to begin the labor intensive process of revision.

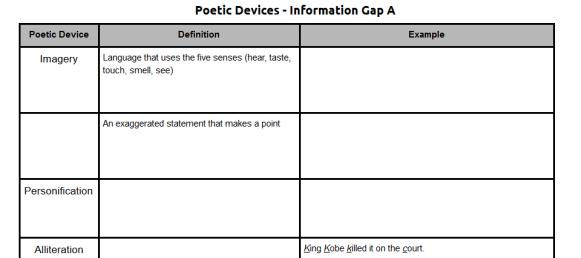

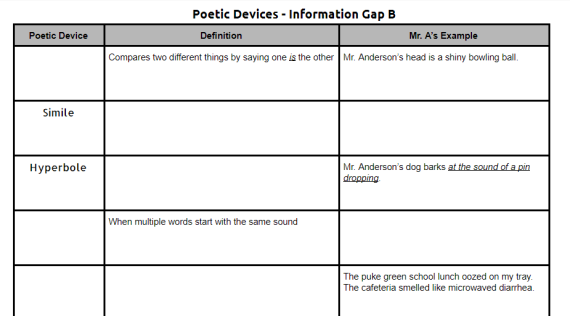

- To make sure we’re all on the same page with language, we begin this step by tabling our drafts and diving into language with an “information gap” activity. Students partner up, sit back to back, and try to fill in the blank spaces on their handouts. While each student has the same information on their sheets, the blank spaces are different. Since they can’t look at each other’s sheets, they have to do a lot of talking and thinking to complete their sheet. The student’s partner would have the B sheet, the mirror opposite of A. The order is different. That way students can’t just go “what’s the 2nd box on the first line.” Here are a few lines from the two different sheets so you can better visualize what I’m talking about.

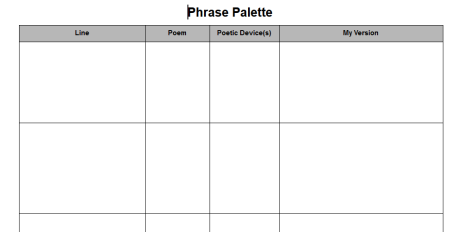

- Now that students have a resource they can turn to for figurative language, it’s time to dive into the language of the poems. I ask students to complete a “phrase palette,” a simple organizer where students copy down lines they love from our mentor texts, figure out what (if any) figurative language is going on in the line, and then try to copy it for their own slam poem. This is always harder than I think it will be, so plan accordingly. Here’s what it looks like blank.

- Once this is done, students fix up their drafts by revising their language. They use the information gap and phrase palette to help them. This is also when I do most of my individual conferring.

- The final step in this phase involves adding some killer rhymes to our poems. We begin by checking out/annotating/choral reading the best rhymes in the mentor texts we’ve been using. I do a short mini-lesson on inner and outer rhymes. I show them rhymezone.com. And then I give the class the first line of a poem about going to school. I tell them to write the next three lines of the poem, paying special attention to adding inner and outer rhymes. The key here is using a first line that has a lot of simple words to it. For instance, students had a lot of fun coming up with rhymes based on this first line: “I woke up, put some clothes on, and walked out the door.”

Presentation: Practice, practice, practice!

- To get ready, students read to the wall (your ears and eyes catch mistakes your brain misses), read to each other, record and listen to themselves reading, etc.

- I don’t do a lot of peer feedback because it’s an incredibly challenging skill that requires months and months of intentional practice. In my experience, students usually just pick at surface errors in each other’s writing. Afterall, this is what their teachers usually do to their work. The problem is that this doesn’t improve writing at all. It just makes folks not want to share.

- On the final day, I’ll throw anything and everything at kids to get them to present. Candy, extra points, names on the wall, whatever. We clap, hoot, holler, and snap every time we hear a great line.

Phew! That’s it. Like I said earlier, this unit produces amazing writing from my students. Many of them reference it as their favorite unit during the end of quarter/year reflections.

I put together a sparse Google folder with all of the handouts I referenced above. Feel free to take, copy, modify, whatever!

One comment