Category: Non-Fiction

A Million Different Directions

One by one, tiny pixelated faces began populating the grid on my monitor.

“HEY! LET’S SEE WHO’S HERE! WOWOW! I MISS Y’ALL SO MUCH!” I shove my face towards the camera, checking out my pores and zooming in on my flared nostrils for comic relief. A few students giggle, but most of them seem pretty nervous. Maybe I’m just projecting my own anxiety on them. Probably a combination of both.

For the next thirty minutes we engage in our first ever virtual check-in. The kids who try to dominate class discussion try to dominate the virtual space as well, gabbing effortlessly about the latest news they’ve heard. Some of the less extroverted kids appear only as half moons at the bottom of their video window, the top of their heads stuck like hesitant suns unsure whether or not to rise in the morning. Dogs and babies make appearances. Every now and then a parent walks in and waves. There’s no agenda or clear instructional purpose.

I held this virtual check-in because some parents and kids asked me to. And because I know other teachers are doing it. I know other teachers are doing it because social media is awash in stories, slices of life, and think pieces about the intersections of the Coronavirus and public education.

“HERO TEACHER READS STORIES OUT LOUD TO STUDENTS EVERY NIGHT”

“TEN WAYS TO USE ZOOM TO TAKE YOUR VIRTUAL TEACHING TO THE NEXT LEVEL”

“TEN WAYS USING ZOOM VIOLATES YOUR STUDENTS’ PRIVACY”

Some posts make me roll my eyes, and others make me jealous inspire me to do things like hold the virtual check-in described above. Then there are the posts that hollow me out. The statistics about the percentages of children who rely on school lunch for food. About inequity in instructional practices. About the connections between quarantines and domestic abuse.

I know I’m not alone in my panic. Every morning my inbox is full with frantic questions from students and their families. When will you begin virtual teaching? Can you be virtual during the same hours as the school day? When will you be sending out a detailed list of instructional activities and due dates? Why aren’t you grading anything? Why are you grading anything? How can I make sure my child is ready for 8th grade/high school/college/life?

I have no idea; I’ve never been here before. None of us have. I don’t fault any families for trying to do what they think is best for their child. In the face of so many needs, I just don’t know what to do.

There is a paralyzing amount of information to take in, much less sift through critically and responsibly. What is my charge? How can I best help students right now? And what if what’s best for students isn’t necessarily what’s best for me and my family?

My family, like many, has been fractured by this. My wife must remain tethered to her work computer because her company expects their employees to be online at all times. (So much so that they actually track when someone is online and when they’re not. This is apparently somewhat common among white collar jobs. As a teacher, this combination of surveillance and technocratic accountability gives me the heebie jeebies.)

This means I’m entertaining my 21 month old daughter. The notion that I could hold some sort of virtual class, concoct meaningful lessons that are developmentally appropriate and accomplishable without teacher intervention during this time is ridiculous. Toddlers are anti-routine. The Coronavirus is anti-routine.

I’m incredibly fortunate to have my mom and her partner close by. They have generously agreed to watch Joelle for a few hours during the day. During those precious hours I rush through my daily teacher upkeep (so many emails!), complete my chores, maybe try to fit in some exercise, and do whatever other random things pop up. My ADHD adds another layer of chaos to the situation. I depend on those hours to maintain some sort of status quo.

Right now, my status quo is NOT healthy. It is heavy. It is tempered by the fact that my students and I are all stuck at home. It is bloodshot from the trauma. The statistics. The daily news of a world on fire. Elected officials bartering human life for stock profits. Communities reeling from waves of loss. Everyone being pulled in a million different directions at once.

Against and within this backdrop I wrack my brain for some direction that feels ethical, moral, and just. Right now it’s the best I can do to think small. Reduce the size of my world to something manageable. I can be gentle with myself as I steal away from the country’s obsessions with standards, scores, and scales. Hold myself and those I love close, pick a direction, and move. One foot in front of the other.

Photo by Evan Dennis on Unsplash

What Am I Doing? Coronavirus and the Teaching Unknown

We are in a global pandemic and everything has changed. Cortisol has flood my synapses. My neck, shoulders, and back feel like they’ve been fused together in a painful patchwork of rigor mortis. Some of this anxiety isn’t new; I’m always on edge. It’s in my guts.

That’s one of the many things I love about teaching. It harnesses and channels my anxiety. It shapes my nervous energy into a recognizable form that I’m intimately familiar with. It powers my lesson planning, classroom management, and entire teacher persona. It pushes me past the torpor that begins setting in anytime I’m directionless.

I’ve had a lot of time to feel directionless this week. The traditional boundaries that I’ve hewn to over the last decade have dissolved. My anxiety has nowhere to go. And in the closed network that is my neurological system, anxiety has to go SOMEWHERE. Otherwise it’s just a corrosive lake eating away at my insides.

Like many others, I hate being trapped in the gray, in those indeterminate spaces where options and vectors spin out. This is why I get extra antsy on snow days. As soon as it starts snowing, I become consumed with figuring out whether or not I’ll have to go into work the next day. It’s not the job that I hate (I LOVE TEACHING!), it’s the unknowing. Snow day anxiety is nothing compared to this.

Because I know what to do with a snow day. I play with my daughter. Watch movies. Bounce around the house stuffing my face with the heavenly cookies my wife bakes whenever inclimate weather strikes.

But this isn’t a snow day. It’s an unprecedented global pandemic that has upended the social and professional fabric of my life and the lives of my students.

Last Friday we were instructed to pack up our stuff and not come back until the middle of April. Four weeks. The guidelines for teachers in my district are anemic at best. We can post work, but it has to be review. Nothing new. And nothing can be graded. That’s it. These guidelines make sense, and I take no umbrage with them. I mean, what else am I supposed to be doing?

Well, based on the posts clogging my various teacher social media feeds, I should be downloading Zoom, holding video conferences with students, designing passion projects, etc. These things all sound great, but I’m not trained to do any of them. Distance learning is a legitimate subcategory of pedagogy with its own thought leaders, philosophical debates, and learning curve.

You don’t just start “doing” distance learning the same way you don’t just start teaching. Any teaching is serious, and anything serious requires intentional study and practice.

I’ve dipped my toes in and put some stuff online for my students. They have an online Coronavirus Notebook to help them keep track of their experiences throughout this historical moment. I give them daily focus questions and prompts. Insert a video time capsule where you record yourself talking about everything you’re eating, drinking, watching, feeling, and doing. Use a Creative Commons website to find an image that symbolizes your week and write about it. Etc.

So is this all I’m supposed to be doing for the next three weeks? Let’s say that it is. That plugs up one stream of anxiety while opening up another. What am I supposed to do when I get back from these four weeks? Should it be new? Should it pick up where we left off with some minor modifications? What role should the Coronavirus play? How does my moral and professional duty as a teacher intersect with an unprecedented public health crisis?

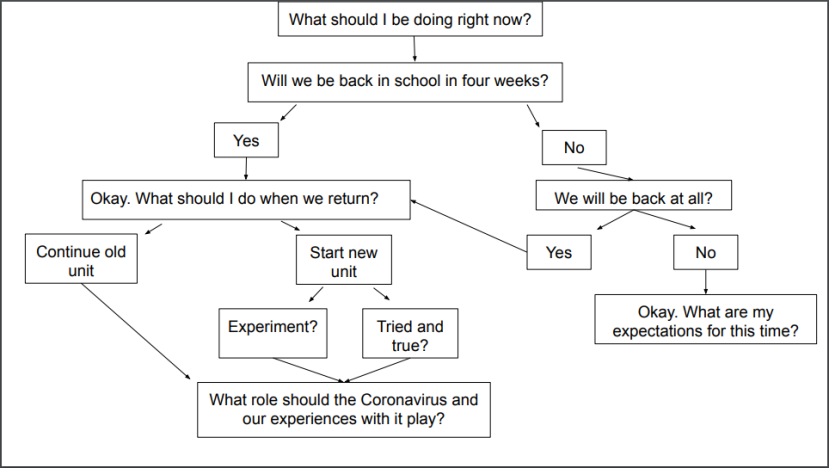

I created a flowchart to capture the manic sequence that’s hamster-wheeling in my brain. Here it is.

It’s an endless loop. A recursive cycle that folds into itself the the more I try to pin it down. The second I stumble upon a fruitful avenue (maybe I could do a unit on X!), my anxiety barges in like a toddler, picking everything up and depositing it somewhere else. While screaming.

I can’t really think of a conclusion for this post, just like I can’t come to a conclusion about what’s going to happen in the coming days and weeks. The key for me is to avoid the analysis/paralysis that often results from trying to think about too many things from too many angles at once. So I’m going to stand up right now and make a sandwich.

Four Weeks

NO SCHOOL FOR A MONTH! NO SCHOOL FOR A MONTH! NO SCHOOL FOR A MONTH! MR. ANDERSON, WHAT’S WRONG?

The muscles holding my face together must have gone slack as my brain chomped its way through a variety of unprecedented scenarios. I swiped down on my phone for what must have been the five hundredth time that day to verify that this was indeed happening.

It was.

The energy inside the school had congealed this week, and now it was heading towards the surface like a fresh zit on one of my student’s foreheads. By Friday morning, the day of the announcement, we were frothing at the mouth for some sort of information. In the absence of official channels, everyone became an insider. Group chats lit up as teachers speculated about what would happen next. Kids swore up and down that their mom worked with someone who got their hair done at the same salon as the superintendent. Everything began with some form of “You didn’t hear it from me” or “It’s not official yet, but…” In truth, no one knew anything.

My first two periods that morning were easy. No one knew anything, so students were content (enough) to do their independent reading for our new unit. By the time lunch hit the day was beginning to feel almost normal. The weekend was unfolding before me like it always did, with its combination of chores, family time, and enjoyable but stressful lesson planning.

Five minutes before lunch ended the news landed. It was official: four weeks “off.” Now, students aren’t supposed to have their phones on them during the day, but they all do. I knew that if I had just gotten the Tweet, so had everyone else. Before my mind could begin processing what was about to happen, kids started pouring into the room.

I commanded them to sit down and start reading, but my heart wasn’t in it and they knew it. Some humored me and opened up their books. Some even started reading. I went back and forth about what to do. Part of me wanted to enforce the day’s silent reading lesson plan. But another part of me wanted to be realistic. If I was a 7th grader in this exact situation, what would I want? What would I need? Getting middle schoolers to sit still is a challenge in the best of times. What about during a global pandemic, facing an unprecedented school shutdown?

I made up my mind: we were going outside. I didn’t have a plan. I didn’t have any games or sports equipment. We didn’t even have a field for them to run around in, just a long stretch of manilla concrete dotted with uncomfortable benches at puzzlingly random intervals. But it didn’t matter. The kids needed to move and I needed to be still. What the hell had just happened?

I leaned against some metal fencing and squinted through the early spring sun. Groups of boys raced up and down the concrete, hooting and hollering about who was the fastest. Squads of girls gathered around cell phones, recording TikTok videos of themselves dancing and lip synching. It was surreal.

After touching base with the handful of kids who were hanging out by themselves, I let my thoughts spin. The instructional sequence I had spent the last two weeks drafting, iterating, and refining was now moot. The seating charts and group activities and anchor charts I had dutifully created were now useless. I wasn’t upset, just lost.

At 2:24 students raced out of the building and into the waiting mouths of school busses. Some students hung around after the final bell, their eyes communicating what their mouths wouldn’t: was everything going to be okay? What was about to happen? I offered what reassurances I could and packed up my own things. I floated out of the building. Nothing felt real. Students, cars, trees, everything around me looked two dimensional. I felt untethered.

The following days didn’t do much to ease my confusion. Every thumb swipe of my phone seems to yield new developments. New vectors for what the next month might possibly bring. For now, I’m clinging onto those four weeks. 28 days. 28 stepping stones guiding me through this miasma of unknowing. In time, the students and I will return to the classroom. We will again be sheltered by the predictable rhythms of assignments and lunch periods and hallway transitions. Until then, I float.

There’s an Octopus Living Inside of Me

“Who is there? What does it feel like?” my therapist whispered.

I placed my hands over my sternum and breathed deeply. I tried to aim my breathe at the exact spot my hands were covering. I couldn’t quite decide what it felt like. Opening a massive, ancient tome that’s been collecting dust for hundreds of years? Using the jaws of life to pry open a particularly nasty car wreck? And then it came to me: an octopus.

An octopus was living inside my chest. More specifically, it had nestled itself into the space between my breast bone and skin. The octopus had spread its tentacles through muscle, bone, and sinew. It reached into every inch of my body. It’s worth noting that despite the picture at the top of this post, my octopus has a much more cartoonish design to it.

The image made perfect sense. The feelings of panic and tightness I frequently experience could be the result of the octopus flexing and pulling at my nerves and muscles. The waves of shame that regularly wash over my face and torso could be the result of the octopus squirting its ink into me. The octopus immediately joined The Critic, The Monster, The Gatekeeper, and the rest of the parts I had previously identified during my time using the Internal Family Systems method.

Internal family systems 101: Internal Family Systems is a therapeutic model that treats the patient’s inner world as a family gathering. The wounded and painful parts of our psyche are given names and identities. They all hang out together. These parts are in varying levels of conflict with the Self, our essence and core. Suffering happens when we “blend” with our parts and they take over, causing us to forget who we are. Healing occurs when the patient is able to heal the wounded parts and restore a sense of balance to the internal system. This happens by visualizing the parts, establishing relationships with them, and conversing with them. There’s lots of visualization, self-reflection, and breathing. IFS is obviously way more detailed and complex than this, but hopefully you get the gist.

A brief example from my own practice. Like many people, I have a rapacious inner monologue. I have personified it as The Critic, a figure who hangs out in my psyche and points out everything I’m doing wrong and what I should have done instead. Sometimes the inner critic is helpful, but mostly he’s a pain in the ass. Some of the work I’ve done in therapy has been to recognize when The Critic is talking in order to establish a boundary and help him understand that everything is okay; I got this.

Normally I’ve been able to interface with all of my parts. I talk to them and they talk back. Something was different about the octopus, however. It felt almost alien. Not only did it refuse to talk, it refused to wake up. In my visualizations, the octopus was in a deep sleep. Nothing I did could garner a reaction from it. So my therapist told me to keep breathing into the space and telling it that I was there with it.

For the remainder of the week that’s what I did. I imagined tickling the underside of the octopus with my breath. I visualized putting pressure on its tendrils by filling my lungs with air. But no matter what I did, the octopus remained silent and inert. And then something happened. I was sitting for my nightly meditation when I noticed an absence where the octopus normally sat. I breathed and breathed, using the air filling my lungs as a searchlight to scan the depths. But nothing was there. Then, a new feeling began to emerge like a submarine rising to the surface after years of dormancy.

It felt like what I imagined being stabbed with a knife might feel like. A sharp, one inch incision appeared right above my heart. It burned and smoldered. I pulled in The Analyzer, the part of me that loves to think things through from multiple perspectives, and tried to figure out what was going on. It dawned on me that I’d experienced this scenario before in video games. In some games, the player has to do a certain amount of damage to a boss before the weak spot appears. Shoot the armor off and you get access to the heart, for instance.

Is that what was happening? Was the octopus guarding a deep emotional wound? Was the octopus protecting me from the wound or the other way around?

The wound disappeared after a few minutes, and I haven’t been able to find it since. Not only that, but the octopus seems to have faded a little. Maybe my breathing was a threat and it sunk deeper into my tissue to hide. I literally have no idea. Hopefully it will reveal itself again. Until then, I’ll keep doing what I’ve been doing. Hold the space. Breathe into the space. Hold. Exhale. Repeat.

—————————-

Photo by Isabel Galvez on Unsplash

The Emergence of Race and Capitalism in Colonial Virginia

American capitalism requires American racism. We can trace this country’s race-based oppression to the political economy of the colonial era. More specifically, to colonial Virginia. By the end of the 1600s, the colonial elite in Virginia had united an unruly society by instituting a racial hierarchy. The combination of private property and anti-Blackness they created became the standard for many of the colonies.

The 1622 Massacre and the Invocation of Crisis

The Virginia Company quickly realized that the best way to accumulate wealth was to rely on tobacco. The new crop was lucrative, but it was also labor-intensive and expensive to harvest. In addition to the expensive cost of labor, the Company flooded the market with tobacco. The resulting overproduction lowered profits. In order to make more money, something had to change.

An opportunity to do just this came in March of 1622 when indigenous tribes from the Powhatan Confederacy decided to launch a combined counter-attack against the ever encroaching settlers. They killed colonists, burned corn crops, and raided settlements. Over ⅓ of the colony died the day of the attack.

The Virginia Company elite used the attack and resulting devastation to clamp down on the colonists. They barred anyone from growing corn or hunting, claiming that these activities left the colonists open to attack. They ordered survivors to abandon their plots of land and relocate to a central position. Living in a centralized location would help guarantee security, they said. The Colony Council then decided that in order to grow corn you had to first have a corn-trading license. They distributed these licenses to themselves and no one else. As a result of the 1622 massacre, a group of twelve Company men were able to seize land, consolidate power, and control the flow of food.

The value of corn skyrocketed due to scarcity. And the only way to buy it was to trade tobacco. Unfortunately the price of tobacco had fallen due to overproduction. Since the value of tobacco went down, the majority of tenants (and the planters they were working for) struggled to make enough to survive.

Colonial Labor and the Transition to Chattel-Bond Servitude

Tobacco was labor-intensive and expensive to grow. In order to remain profitable, the planter elite needed to increase their margins. Since the market had been flooded with tobacco, the only way to increase profits was to decrease costs. The traditional bond laborer needed to be more cost effective.

For the majority of the 1600s, the VA colony’s workforce was made up of primarily English workers. They were referred to as bond laborers because they signed contract agreements with the Virginia Company and its stockholders before they boarded ships to the colony. The typical bond laborer expected to work as a “tenant-at-half.” This meant they agreed to work for a Company planter on Company land for half of the profits. The Company was responsible for supplying bond laborers with clothing, food, shelter, and a plot of land upon work completion (typically 4-7 years).

To reduce labor costs, the VA elite decided to change the established English conditions of bond contracts. After the change, tenants arriving at the colony often found themselves assigned to private planters on private land. Furthermore, workers were now expected to pay for their own food, shelter, and clothing. Since the price of tobacco was so low, tenants were barely able to make enough money to survive.

Rebellion and Social Control

The situation was dire. Food was scarce. Land was privatized. A steady stream of European laborers fed the environment of discontent. No longer could laborers expect to hold public office or find workable and ownable land for themselves. Members of the colony’s workforce began expressing their anger in a variety of ways. Some ran away to indigenous tribes. Others linked up with African slaves and burned tobacco crops to protest over-production.

The various rebellions culminated in Bacon’s Rebellion in 1676. Freemen, slaves, and bond laborers banded together to resist. The plantocracy was terrified. The threat of a united labor force pushing back against the plantation system was immediate. They needed to divide the laborers. They did this by creating a system that allowed one group (poor Europeans) to control the other (African slaves). But in order to make this a viable solution, the planters needed access to cheap labor. They needed someone for this new class of landless Europeans to manage.

In the 1680s, the English gained access to a steady supply of African slave labor by way of a treaty with the Dutch. The unfettered access to African labor was counterbalanced by a marked decrease in the availability of European labor. King Charles II made it harder for the Virginia Company to recruit poor European workers. Colonies in the Carolinas and Pennsylvania opened up, creating a place for poor Europeans to move to. The price of tobacco began to rise, improving the lives of planters and their mostly European tenants.

Prior to the early 1680s, most African slaves came to the Virginia Colony by way of Barbados. African slaves who labored in Barbados were often able to learn some English. This wasn’t an option for the new slaves abducted directly from the African coast. They struggled to acclimate and learn English. They were unable to communicate, plan, and find common cause with poor Europeans workers, leaving the new slaves alienated and alone.

In addition to these larger changes, a newly constituted Virginia Assembly instituted a series of legislative moves to place Africans in a state of permanent chattel servitude. Normally, under English common law, the status of a child drew from the status of the father. The Assembly flipped it so that a child’s status was now linked to the mother. This allowed European planters to increase their supply of hereditary chattel labor by raping their female slaves. Additionally, new antimiscegenation laws meant any European woman who married someone of African descent became property of her husband’s owner.

A Community of Privilege

The Virginia and Maryland colonial assemblies used the law to create a community of privilege bound up in skin color and status. Non-Europeans were unable to vote, own property, testify against Europeans in court, and buy/own anything resembling a weapon. On the other side, European slaves were given “freedom dues,” corn, weapons, and other living essentials. Poor whites were often placed in positions of authority over African slaves. This is because the community of privilege is contrapuntal in nature. Every European privilege is built upon the denial of freedom to Africans.

Those in power needed to create a new class that was so attractive that poor Europeans would see themselves as similar to the English elite. This is the origin of the white race, a legal category that begins showing up in official documents around the 1670s and 80s. The lack of historical precedent over a distinctly white race and the visibly distinct difference in pigment made whiteness a perfect way to maintain social control.

This is the origin of anti-Blackness, capitalism, and white privilege in the U.S.

Works consulted for this post:

Birth of a White Nation by Jacqueline Battalora

The Invention of the White Race v.1 and 2 by Theodore Allen

Settlers by J. Sakai

A Changing Labor Force and Race Relations in Virginia 1660-1710 by T. H. Breen

Colonists in Bondage, White Servitude and Convict Labor in America 1607-1776 by Abbot Emerson Smith

Image credit:

“The Plantation” by

Licensed under CC0 1.0

A Contained Existence: Ritual, Routine, and My Life on the Grid

I experience life through a series of shifting grids. Everything about the way I process information suggests right angles, coordinate planes, and compartments. Anytime I meet someone new, I assault them with a barrage of out of context and somewhat inappropriate questions: What music do you listen to? How was your childhood? What’s your relationship with your family? What were you like in high school? What are your favorite shows? My brain yearns to place everything and everyone into various interconnected frameworks. Everyone’s answers also act as a mirror, allowing me to engage in continuous rounds of self-assessment to make sure I stay within one standard deviation of what I consider to be normal.

The tendency to fix everything to a grid permeates every aspect of my life. When I was little kid, I told my mom how I enjoyed tracking syllables with my left hand. I would take sentences and count them off into alternating groups of 3, 4, and 5. The goal was to make the final syllable of every sentence end on a particular finger.

Heavy metal, my favorite genre of music, fits seamlessly into the grid. Every band taking up residence in my brain combines jackhammer force with the precision of quartz chronological movement. “Still Echoes” from Virginia metal band Lamb of God is a perfect example. Listening to the drums, guitars, and vocal patterns feels like spiraling out from the center of Fibonacci’s golden ratio pattern.

For this reason, my jogging playlist always contains a single song on repeat. No surprises and no shuffling. Just the same two minute chunk looped. It takes a certain kind of song to stand up to this obsessive level of routine. The song has to be relentless and consistent in beats per minute. Although I try to mix it up every few months, I keep coming back to the staples: Slayer, At the Gates, Lamb of God, In Flames, and Darkest Hour. The one exception here is Usher whose banger Scream enjoyed a couple summers of looping.

I’ve been listening to the first two minutes of Darkest Hour’s The Sadist Nation during every run for the last five years. It never gets old or loses its edge. Every listen is a fresh marching order, a call for muscle and sinew to propel the body forward. 1’s and 0’s, on’s and off’s, starts and finishes. I can’t stand jazz for this reason. The organic ebb and flow of improvisation, the rhythm changes, the fluidity of it all claws at my need for repetition and symmetry and containment.

Schools are perfect for me. In most schools, everything that happens slots nicely into a grid. Bell schedules, assignment schedules, curricular planning, everything is rationalized and consistent. I love it. Every school day is a perfect assemblage of self-contained rituals. I can tackle anything as long as it’s fixed to some sort of repetitive grid.

Ritual and repetition help me manage my ADHD. They place boundaries around everything. During summer and winter break, I keep to the same schedule. Wake up around 5 and play video games until 9. Then, work on writing until around 11 when I do some form of exercise. My afternoon is lunch, nap, reading, then YouTube until my wife gets home. Every day. Without such a setup I drown.

I’ve always been an all or nothing person. I recently had my wisdom teeth removed, an experience that left me swollen on the couch for days. I didn’t brush my teeth. I collapsed on the bed every night in the clothes I had been wearing all day. My diet consisted of slurping down ice cream, apple sauce, and ex lax whenever I felt like it. After a week of being off the grid, I was able to begin inserting modules of routine back into my schedule. Mercifully, my life is once again fully contained within blocks of reading, writing, exercise, and socially acceptable hygiene practices.

My contained existence brings me joy because it allows me to meet life on my terms. Within constraint lies my personal freedom.

The Teacher I Want to Be: A Slice of Life

I sometimes imagine that teaching is sort of like playing in a local band. You’re the opening act for some larger performance. As the opener, not everyone is going to like you. Most of the audience didn’t come to see you, and they simply have to tolerate you. They bought a ticket to the show, they’re with their friends, and they’re excited for the headliner, so they stick around. But there are always a few diehard fans who are ecstatic to hear you play. They know the words to every song. They come early and stay late. When everyone else is on their cell phones, the diehard fans are pumping their fists and sharing that moment with you.

I use this analogy not as a way to compare teachers to rock stars (shudder), but as a way to think about the unique connections that can form between teachers and students. What starts out as a fandom built on the superficial aspects of performance (I love his energy! or He’s awkward like me!) can, over time, develop into a meaningful relationship. This is more the exception than the rule.

The analogy speaks to my belief that students will connect with certain teachers for specific and often idiosyncratic reasons. Some teachers might collect more fans than others, but even the quirkiest among us can make a difference in another human being’s life.

Over time, relationships between teachers and students can grow beyond the hierarchical structures common (and somewhat necessary) to schooling. If a student I taught last year stops by after school to talk, I’m able to engage with them holistically. We can interact with each other outside the realm of immediate academic transactions. Discussions of academic progress can still play a role; they just don’t have to be the focus.

Last week I received a Facebook message from a former student asking if he could come visit me at school. Since his high school classes don’t start until later in the morning, I told him to stop by around at the start of my first planning period. The two of us had kept in sporadic contact ever since we first hit it off four years ago when he was a student in one of my 7th grade English classes.

As he left my room and I scurried off to my meeting, I was struck by how joyous it felt to see him and talk to him about his life. To watch a life grow and stretch and push outwards. He is finding his groove, and I am so proud of him.

Although this might reflect poorly on my character, I’ve always looked forward to the possibility of former students reaching out and reconnecting with me. I guess it’s a reminder of what I love about teaching: growth, relationships, knowledge, the dialectical possibilities of minds interacting with one another.

The rest of the day was a fairly typical middle school day. I left the building exhausted, overloaded with work, and saturated with the tiny victories and big defeats that sometimes seem to characterizes my life as a teacher.

After the school day ended, I found myself in a situation inverse to the one described in the beginning of this post. Now, as I’ve written about before, I enjoy emailing people whom I admire. I’ve been lucky, fortunate, and privileged that some of my correspondences have blossomed into mentorships, leadership opportunities, and professional growth.

I’m currently co-writing a piece with Julie Gorlewski, one of my academic idols. We had a productive Google Hangout session yesterday, speaking through video chat about teaching, the state of public education, and our article. Julie is in every way my superior. She has published widely, taught in a variety of settings, and knows infinitely more about education than I probably ever will. But she treats me as an equal. I left our 75-minute conversation feeling valued as a thinker, learner, writer, and person. She took my ideas seriously and validated how I perceive the world. This, to me, is some of the raw power of education. It reminded me of who I want to be as an educator. Of how I want to interact with everyone I come into contact with.

As I reflected on the day, I was struck by the richness of education. By its ability to forge powerful relationships through generations and influence the outcomes of multiple lives. Most of all I felt an almost cosmic connection to those around me. In my former student and my new co-author, I felt my place as an educator and a human being.

Using “This I Believe” Podcasts to Elevate Student Voice – NVWP Summer ISI – Day 13

Welcome to the Northern Virginia Writing Project’s 2016 Invitational Summer Institute! I’ll be blogging the demonstration lessons and the various activities occurring during our four-week duration. Find out more about the NVWP and the National Writing Project.

We kick off our final week of Summer Institute with Joanne Mann. She’s going to present to us on using “This I Believe” podcasts to elevate student voice. Can’t wait!

Joanne begins her demonstration by having us arrange ourselves along a value line as she reads us a series of affective statements such as “Violence is sometimes necessary,” “Everyone is basically good,” and “All students should be required to speak English.”

Quickwrite: Which one made you think the most? Did others’ positions influence where you stood?

“Love lasts forever” probably resonated with me the most. To begin with, I don’t believe in soul mates. For me love is something that’s built up over time through the accumulation of shared experiences and the continued rejection of outside threats. I also try to think about my family and spouse dying a few times a week. I started doing this after reading about it on a mindfulness website. As a way to remind myself of life’s impermanence and to truly live in the single moment. In one sense, love lasts forever because it, and the memory of it, can remain in someone’s mind. Time’s up!

Here are the objectives for today’s lesson:

We’re doing this for a few reasons. It helps students develop technology skills. It helps them to reflect on their voice and to understand that their voices matter.

We listen to a podcast on Muhammad Ali from Muhammad Ali. This is the first draft reading; we sit and take it in. After this Joanne passes out the transcript of the podcast. Ali discusses his confidence growing up and how Parkinson’s Disease has affected him. The story culminates in Ali holding the Olympic Torch at the 1996 summer games. As he felt his trembles take over he heard a thunderous ruckus storming down from the stadium. Terrific story.

Next we do our second draft reading, annotating the transcript as we listen again. We share out. I discuss how Ali’s story seems quintessentially American. The idea that will and determination can triumph over everything. Others mention that Ali must have experienced failure and disappointment, but he chooses to focus on the triumphant aspects.

Then we create categories to make observations on about the text and fill them in on the following sheet. She runs is through two examples first (the guided release model) before having us work with our partner:

We come up with categories like theme, details, and structure/organization. After sharing out Joanne has us turn out attention towards another podcast. We have a few to choose from. I choose “A Grown-Up Barbie” from Jane Hamill (all of these come from the This I Believe book). I read it and analyze it for structure, theme, and details. I also jot down anything I notice about the piece. Joanne’s methodology here fits in with the type of model-based analysis currently popular among secondary English teachers.

Now that we’ve listened to a podcast, read two transcripts, and discussed both it’s time for us to create one ourselves.

So, what do we believe? Why do we believe it? What happened to us that created that belief? How has it been reinforced? She passes out a planner (I love planners, btw! I know they’re frowned upon in some circles – and I get it – but my attention deficient brain finds them extremely useful in organizing my thinking). Here’s what I come up with.

After completing the planner we spend time crafting our own brief “This I Believe” essay. The ultimate goal is to then record them using free software (such as the Voice Memos app which comes installed on every iPhone). Let’s give it a shot!

“Honey. This is ridiculous,” my wife said, frowning down at my desk with her hands on her hips. I had to agree with her. My massive white desk, once cramped with books and papers, was now completely obscured by composition text books, histories of education, and expensive books on pedagogy.”

Crud! Out of time!

Joanne ends our lesson by playing a couple examples from her students. Outstanding!

Writing Extraordinary Profiles of Ordinary People – NVWP Summer ISI – Day 1

Welcome to the Northern Virginia Writing Project’s 2016 Invitational Summer Institute! I’ll be blogging the demonstration lessons and the various activities occurring during our four-week duration. Find out more about the NVWP and the National Writing Project.

A different person is the ethnographer for each day. This person is responsible for chronicling the day’s events in any format they choose. As a three-year veteran of the Writing Project, I’m tasked as the ethnographer. Mine is as follows:

Day 1 Ethnography: Summer is Here

Our Fearless Leader (referred to from this point forward as O.F.L.) lets me take the lead for the first ISI ethnography. I know from previous experiences that the first ethnography tends to set the stage for the ethnographies to follow. It typically takes a solid week for most of us to feel comfortable enough to create an ethnography in our own vision. This, of course, makes perfect sense. Purposefully ambiguous expectations, institutional pressures to conform, and the hegemony of the model text make mimicry an understandable solution.

So I’m going to make this inaugural ethnography somewhat short and to the point. I encourage you all to write the ethnography however you want. Personally I’m not really pushing myself. First-person non-fiction narration is where I feel most comfortable.

I survey the room. The future teacher consultants seem split 50/50 on the use of digital vs. analog writing implements. The presence of so many pens might also have something to do with the first day’s spotty Wi-Fi. Michelle, a notebook fiend, might also be unwittingly inspiring some of us to ditch the district-provided laptop in favor of colorful pens.

We’re sitting and writing. This is an abridged version of our morning pages routine, a daily chunk of time devoted to nothing but sitting and writing. I wonder what everyone is writing. I would imagine equal parts diary/journal stream of consciousness narration, checklists and schedules, and clandestine email checking. I notice that many of us are also scribbling away on sticky notes for the ice breaker. OFL’s equally fearless daughter created a neat ice-breaker activity, so many of us are penning our six word memoirs, pet peeves, sin foods, and etc. to place on large pieces of chart paper.

You can already draw a few conclusions about everyone’s personality based on how they chose to complete the sticky note icebreaker. Some place their sticky notes in nice and neat Jeffersonian grids while others prefer a scattershot approach. Some use drawings while others create elaborate mini-essays.

Jokes are made. Mostly of the semi-corny variety best suited for first encounters. I do my usual routine of saying non-sequiturs and mumbling sarcastic comments under my breath. The atmosphere seems pretty typical for this type of function. Light jitters. Appropriately subdued and managed levels of libidinal energy. But like the first day of school, everyone is definitely on their best behavior. I’m looking forward to learning more about everyone’s personality in the upcoming weeks. Ron makes some jokes that exhibit a decent sense of humor possibly sympatico to mine. He also drew a neat looking cartoon spider for his ice breaker.

Lauren Jensen comes in around 9:40. A Writing Project alum/mainstay, Lauren will be running us through the first demo lesson of the Institute. She gets us writing with a question about teaching non-fiction writing. There’s nothing I can say about her that hasn’t already been said by way more accomplished people. She’s hyper-literate, driven, organized, and frighteningly knowledgeable. Lauren comes prepared with a vast array of instructional materials for us. Her lesson is an enjoyable combination of air-tight sequencing with off-the-cuff moments of improvisational commentary. I’m not going to type out much more about it, but if you’re interested I recommend checking out my blog. The time is now a little past noon, and we’re starting to get peckish.

We eat lunch. Nothing too noteworthy to say about it.

Michelle Hasseltine begins our first afternoon session by preaching on the power of social media. I cannot cosign enough. Tweet at authors. Connect with teachers. Engage in conversations. Almost everything good that’s happened to me professionally has come in some way from my interactions with others on social media. Michelle is a force of nature. Great teachers have presence, the seemingly preternatural ability to attract attention in a room. Michelle has this in spades. All eyes are glued to her as she walks us through the blogging process for the Summer Institute. She makes a passionate appeal for everyone in the room to wiggle at least a big toe toe in the waters of social media.

Next O.F.L. provides us with a guided tour through the syllabus with special emphasis on the summative portfolio. Everyone will be writing blog posts, completing statements of inquiry, writing various reflections, and etc. We’ll be in writing groups, reading canonical texts, and more.

That’s it. No linguistic or textual pyrotechnics, no formal experimentation, just a straight-forward, chronological narration of the first day. You heard Lauren Jensen tell the room that the Writing Project was the most powerful professional development experience of her life. I’ve heard the same sentiment echoed by nearly everyone who has experienced the ISI. Personal growth often occurs in fits and starts. It’s my hope that what happens during the next four weeks will reverberate through you for years to come.

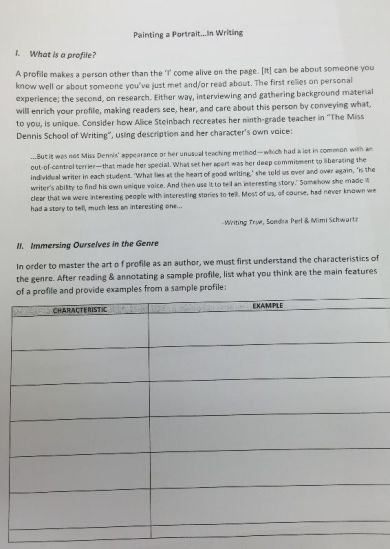

After morning pages Lauren Jensen comes in around 9:40. A Writing Project alum/mainstay, Lauren will be running us through the first demo lesson of the institute. This 3-week lesson cycle involves using profiles in the writing classroom (She gave a version of this during last year’s ISI, as well). She gets us writing with a question about teaching non-fiction writing. Lauren begins by asking us to write down our initial response to the question: What do you think of teaching non-fiction writing to your students? My answers will always be in red.

I love it! Non-fiction writing is perhaps my favorite topic/genre to teach. I’m immensely interested in personal stories, self-expression, and any kind of writing that draws its main inspiration from the stuff of lived experience. Similar statements could be made about all writing, for sure. But personal essay writing is just so wonderful to read, write, and teach.

When it comes to more traditional school-based non-fiction writing like research papers, I’m neither excited nor underwhelmed. I haven’t done a lot of research writing in the past simply because I haven’t spent a lot of time looking into how to do it well. I’ll probably look to remedy this omission in the upcoming school year. I’ve read a few nice essays examining the benefits/pitfalls of classroom research writing and I feel more comfortable wading into those waters.

We share our answers out. Some of us approach non-fiction writing with trepidation while others say they enjoy the structures of fact-based compositions. It’s clear that teachers and students alike hold strong opinions about this. The beginning of successfully teaching non-fiction is unpacking what we mean by the genre. She takes us through quotes from past students who all speak to the point that teachers have pretty much ruined non-fiction for most kids. They find it boring, pointless, and requiring way more editing and revision than it’s worth.

She next points out the disconnect between what many of us have our students read (literature) with what we then ask them to write (5 paragraph essays). So she wants to introduce more “real world” writing, composition that’s rooted in authentic audience, genre, and process. That’s where non-fiction profiles come into play.

She begins by tying her portfolio unit into whatever her students are studying at the time. Portfolios are malleable. They can fit into most units because interesting people come from all walks of life and are found in most texts. Portfolios are also found in a wide array of periodicals such as Rolling Stone, In Style, and the New Yorker. As a result, this unit, although quite complex in nature, allows for differentiation, incorporates pop culture, and pushes students into some pretty complex levels of thought.

She introduces us to the genre with a spirited reading of Susan Orlean’s Show Dog. It’s awesome. We then discuss what we noticed about the genre. It’s creative, it uses facts, it’s funny, there’s an element of narrative, it’s non-fiction, it requires research, etc. It’s a wonderful blend of methods and styles. Above all else there’s a sense of intimacy. Intimacy between both the author and subject and the author and reader. Here’s her process.

Writing a Profile: The Process

1. Profile genre study: What do you notice? Immerse yourself in the genre. Read a lot of them. Talk about them, etc. This is a basic component to most inquiry models.

2. Find interview subject and write a letter of invitation: family, friends, family friends, friends of family. They have to learn how to go out into the community and ask people. Plenty of opportunities here to make bridges with the community.

3. Write contextualization essay: 3-4 paragraphs. Requires each student to do some research and acquire important background knowledge about the interviewee and their topic.

4. Practice with recording equipment: pretty self-explanatory. Never assume that students are familiar with technology. Always teach.

5. Conduct mock interviews / craft interview questions: Practice interviewing people who give 1-2 word answers. Go through a few common archetypes. Problem solve in the moment and try to foresee problems.

6. Transcribe interview and select quality quotes: they transcribe the best part(s). It shouldn’t go beyond two pages.

7. Craft lessons: (based on student work and student requests, like how to select quality quotes) This is a great way to help students practice skills within the context of their draft

8. Draft and revise:

9. Write thank you notes to interviewees: actual notes on actual stationary – the thank you note is a valuable genre!

10. Compile portfolio and class publication / public reading with distinguished guests

You see how the process is multi-layered. It leans on the community. It builds and values empathy. It requires research, reading, and writing. We partner up and go through a genre study using some mentor texts Lauren provides us. The portfolios lend themselves to skillful inferences on the part of the reader. They’re rich in description (about the subject, the setting, the events, etc). Parenthetical asides. These portfolios are masterclasses in studying tone, mood, and writer’s voice. How to select important information from a sea of writing. They’re a great way to start talking about writer’s craft.

The last step of the process is to write out our questions and then interview each other. At the ISI we introduce each other using the information gained from these portfolios. Like a drop of soap in greasy water we immediately scatter to the corners of the floor to find some peace and quiet in order to interview each other. After that we spend the final pre-lunch minutes debriefing about the lesson cycle. While having someone as powerful and polished as Lauren present first can increase the intimidation among participants, kicking off the Summer Institute with such an effective demonstration lesson sets the tone for the rest of our time together.

A few of us share out what we’ve written on our profiles before the ink is even dry. A few of us sandbag our reading with “This isn’t that good…,” a common mea-culpa among growing writers. A few of us who have done this before know how to handle it; we shout out “shut up and read the crap!” We’ll no doubt repeat this mantra multiple times throughout the Summer Institute. By the final week anyone silly enough to begin with such a self-deprecating aside will find themselves on the receiving end of a rowdy vocal chorus. Shut up and read the crap.

Student Made Standards Based Rubrics – NVWP Summer Institute – Day 12 pt. 1

Now we have Nick Maneno. He’s one of the many rockstars of the Writing Project. He is a model for pretty much all of us. He apparently begins most of his emails with, “hmmm..” I think I’m going to start doing that.

Student Made Standards Based Rubrics: An Inquiry Approach to using a Mentor Text to identify standards, develop a Rubric, craft and score a poem.

What a title!

Nick begins by talking about how he isn’t really that into rubrics. But he works in a school system that uses Standards-Based Grading (want to learn more about it? Look up Rick Wormeli. He’s sort of like the guru). Nick says he likes neither rubrics nor standards, but he has to make it work. So this demo lesson is an attempt to make all of this work. Please note that this demo lesson write-up will be devoid of any authorial commentary by yours truly.

Quickwrite1: List some things you do for fun and recreation.

-reading/writing

-video games

-YouTube

-pretend to exercise

-eat

Now, pick one thing from the list and keep it in your head while reading the following poem. (An intention for reading)

Then he tells us to read it again, only this time looking for literary elements and text features. What standards do we see being used here? We discuss movement, font size changes, capitalization, onomatopoeia, author’s purpose, exaggerated spellings, non-standard use of line breaks and white space, (link here to Katie’s presentation), alliteration, strong verbs/word choice (link here to Janique’s lesson), a title (link here to Michele’s lesson), parallelism with the ‘ing’ forms, we gerunds.

We get ourselves together in groups of three. Three is the perfect number, he says. You get a diversity of opinions while still allowing a space for everyone to give their opinion. We add polysemous words, some repetition, the form paralleling the content of the poem, and more. (Nick says here that collaborating and turning and talking with partners is the most important part of his classroom. Nick gives a plug for “Teaching with Your Mouth Shut [which I’ve never heard of! Amazon, here we come]). I’ve already learned so much from just this conversation.

So we’re all noticing here. Nick shows us what his fifth graders noticed:

Nick is going to have us write our own poem using the Kwame Alexander as a mentor text.

The first step is to compose a rubric for the poem we’re about to write, using the Virginia writing standards of ‘Composition,’ ‘Expression,’ and ‘Mechanics.’ I don’t get very far. We work on our rubric individually, then we go back to our group of three and try to put it together. Nick tells us that he doesn’t really care that much about the rubric. The important part, he says, is the dialogue parsing out what it is that makes a poem successful or not. Nick ties this into the Inquiry model. Immerse students in the genre, and then have them create a rubric for what they’re about to create. Here’s the rubric Nick’s class came up with.

I am again, for the enteenth time this summer institute, reminded of Katie Wood Ray and “writing under the influence.”

Nick wants us to now write a poem emulating Kwame Alexander’s poetic form following the class’ rubric. I’ve written mine about one of my hobbies: watching Northern Lion’s YouTube Let’s Play videos after work. I do this religiously every day. I’ve been watching his videos for months, and by now I feel like part of the family. Interesting connections here with online communities, video games as an industry, YouTube as a public sphere, etc. Here’s my draft!

Now he has us ask ourselves the following questions: What did I learn by doing the rubric? Did it help me learn? To be honest, our group was more interested in gabbing about our poems than we were discussing the rubric portion. Nick then shows us a powerful slide reflecting what his students thought about the rubric process.

Next up is Essaying. Nick sets us up with a T-Chart. He calls this the Chronologic method, which I love. Chronologic writing comes from Paul Heilker. Left side is “What I think the poem is about” and the right side is “Why I think Like I do.” He then reads us a poem line by line. After each line he stops reading and we keep a running log of what we think it’s about and why I think the way I do.

The evidence falls into five categories: logic, life experiences, intuition, emotion, and text evidence. These are the five paradigms of essay writing, he says. This type of line-by-line analysis is an excellent way to promote the essay as a tool for understanding. Nick is interested in reclaiming the essay for ‘writing to learn’ instead of ‘a record of learning.’ He mentions that the French verb ‘es say’ is ‘to try.’ So he encourages us to use tentative language (instead of the authoritarian language often taught alongside the essay). Coming to understanding through stages of measured analysis and thought. After each stage the class discusses our various interpretations and reasonings. We’re encouraged to ponder each new perspective, adding it to our own if we want. The essay becomes the combination of the Chronologic thinking. Claim and evidence moving forward towards a new point of understanding.