Category: Genre

When Teaching Narrative, Go Realistic Instead of Personal

Personal narratives are a staple of the secondary English curriculum. I love writing about myself, so why shouldn’t my students? Typically I would push the kids to mine their past for meaningful moments. Students understood this to mean write about something painful. I even had the audacity to get upset anytime students pushed back. This is what writing’s about! I would thunder. It’s not really, though. Or at least it doesn’t have to be. It certainly shouldn’t be for every student.

This year I switched from personal to realistic narratives. I decided it was inappropriate to continue to enact a pedagogy of disclosure. Pedagogies of disclosure require students to relive potentially traumatic experiences AND hold them up for critical feedback from teacher and peer. I had to take a step back, remind myself that I’m an English teacher, and that stories are about windows and mirrors. Vehicles through which we find out we’re not alone and that our lives carry significance.

Realistic narratives can do all that. We brainstormed various protagonists, motivations, obstacles, and settings. We used stage directions and acted out dialogue. There was feedback, revision, and editing. All the typical personal narrative skills without any of the icky required disclosure stuff.

My favorite part was tinkering with made-up details that served the piece without setting off the reader’s BS alarm. I told students that realistic narratives allowed writers to shape their past into whatever they wanted. There was capital T Truth (your airtight memory), little t truth (a detail that might not have been exactly right but served the same purpose), and fabrication.

This genre-bending challenged most of my students, and understandably so. Molding raw experience and trenchant observation into purposeful prose takes decades to master.

As always, I wrote alongside them. I chose one of my few middle school memories: an 8th grade party. I delighted in asking them to guess which parts of my narrative were fictional. I included my realistic narrative below. It’s pretty melodramatic, and it’s obviously the work of an amateur. I wasn’t even able to “finish” it. But that’s part of the challenge (and elation) of writing alongside your students. It knocks you off of your pedestal and humbles you before the power of the word, the story, and the audience.

I can’t wait to try this again next year, this time with an emphasis on fabricating and borrowing details. The unit was a success and students reported a high level of enjoyment. Next time you reach for your memoir or personal narrative lessons, consider shifting towards realistic.

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

Title: Only in Dreams

Colorful holiday lights hung from the ceiling, casting a warm glow over the room. Red, pink, green, and blue reflected off of our faces as my friends and I alternated between talking in groups, chugging soda, and chomping on chips and pizza. We were all in Cheryl’s basement. She lived in a giant house in the country club hills neighborhood of Arlington. Her parents popped downstairs every 30 minutes or so to check in on us and make sure everything was going well.

I had been dying to ask Alicia to dance the entire night. It was the party for our 8th grade graduation, and this would be my last chance. She stood across the room disappearing in and out of a group of her closest friends. Alicia was about my height. She had an athletic frame from years of playing travel soccer. She was everything I was not. Sarcastic, quick witted, responsible, and decisive. Her ability to talk trash was legendary. No one dared to try and roast her. I would catch flashes of her dirty blonde hair as she laughed and danced with her friends.

It was one of those moments when you’re trying not to stare at someone, but that somehow makes you stare at them even more. And everytime our eyes locked, my palms itched and my scalp tingled and my heart threatened to jump out of my throat. Every time I tried to approach her, something would happen. A rock song would come on and my buddy Jeff would tackle me. Or two kids would start roasting each other and everyone would crowd around them to watch.

Time was running out. The party ended at 9, and it was already 8:35. Cheryl’s mom had come downstairs and recruited people to move to start picking up. At 8:40 the main basement lights came back on, killing the vibe. I didn’t know what to do.

Peter: (Moping on the floor, sounding rejected) It’s almost over and I still haven’t asked her to dance!

Jeff: (Punching Peter on the shoulder. Speaking with confidence) Just get up and do it. She’s right over there. Come on, man!

Peter: (Stuttering his words) It’s not that easy for me. Girls love you. I’m, well, me.

Jeff: (laughing) Yea. Not gonna lie; that’s true.

Peter: (whispering quickly) Dude she’s coming over!

Jeff: Go on, get up! (Trying to push Peter up)

Alicia: (Walks over confidently. Sticks out her hand) Okay. Come on.

Peter: (face flushing, looking at Jeff who suddenly jumps up and leaves to get some soda) Wait, what? I mean… what?

Alicia: (Sighing) Don’t you want to dance? (Looking over at her friends) Everyone told me you did.

Peter: (Looks over at Jeff by the drink table)

Jeff: (Nods enthusiastically)

Peter: (Nervously) Okay (takes her hand)

I looked back at Jeff as she dragged me into the middle of the room with surprising force. The opening bass riff from Weezer’s “Only In Dreams” started to ooze out of the speakers.

I didn’t know exactly what to do, and neither did she. She rested her hands on my shoulders and the two of us started to rock awkwardly back and forth. My palms heated up like I was holding onto an exploding star. Strawberry perfume floated up as I felt her place her cheek on my shoulder. Jeff snuck around behind her and started making faces to try and get me to laugh. It worked. Alicia whipped her head up and stared at me. “Jeff’s doing something dumb, isn’t he?” She said.

“Yup!” I replied.

“You guys are idiots,” she smiled. “So where are you going to high school?”

“Yorktown,” I said. “Aren’t you going to some private school in Georgetown, or something?” I knew exactly where she was going, but this would keep her talking.

“Yea. Sidwell Friends. I’m actually pretty excited. They have an awesome girls soccer team.”

“Thanks for asking me to dance,” I whispered.

She tucked a strand of her behind her ear and smiled. “I’m glad we got to do this,” she said.

For the next two and a half minutes, the only thing that mattered was the two of us swaying gently in time to the music. She kept her head on my shoulder and I kept myself from stepping on her toes.

Before the song could end, Cheryl’s mom hollered down into basement that my mom was there to pick me up. I said goodbye to Alicia, Jeff, and my other friends before bolting up the stairs. On Monday at school, Alicia and I said “hi” a few times, but that was it. It was almost like the dance had never happened. A few days later we went our separate ways to different high schools. We ran in different crowds and I never saw or heard about her again.

Harnessing the Power of Purpose and Audience: Authentic Writing in the Classroom – NVWP Summer ISI – Day 14

Welcome to the Northern Virginia Writing Project’s 2016 Invitational Summer Institute! I’ll be blogging the demonstration lessons and the various activities occurring during our four-week duration. Find out more about the NVWP and the National Writing Project.

Our final day of presentations begins with Sara Watkins talking to us about how she uses authentic writing in her high school classroom.

Quickwrite: Think about a writing assignment you’ve given that your students enjoyed. Describe the lesson: what was it? What was its purpose? Who was the audience for the students?

Towards the end of the year I ran the students through a Flash Fiction mini-unit. We read examples, took them apart to see what made them tick, and tried to figure out what the genre was all about. Students then created their own examples of Flash Fiction. I had them concentrate on conflict types, economy of language, and otherwise following the genre rules we discussed. I wanted the students to gain practice with honing in on various conflict types, working through plot elements, and figuring out how to say a lot with a few amount of words. The audience, unfortunately, was just the class. By the end of the year students knew that pretty much anything they wrote would be put up on the walls to be read and discussed with classmates.

BTW, authentic writing is pretty much any genre of writing that is “found in the real world” and written for an audience outside of the school. Authentic writing creates links to the community. Writing for an authentic audience helps children believe in the power of their own voice and their own story. Here are some examples of genres of writing used by non-teachers:

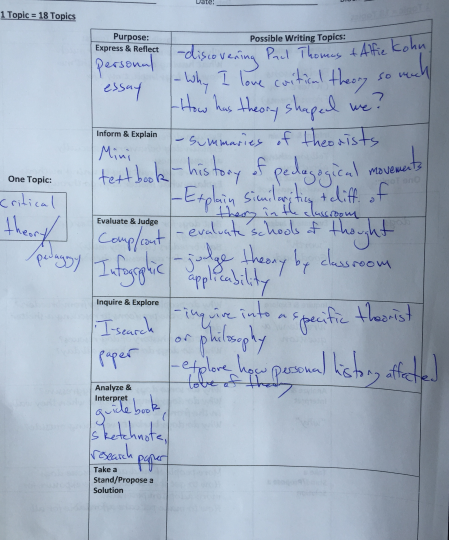

Sara passes out a Kelly Gallagher sheet on approaching one topic in 18 different ways. The left hand column represents six prominent purposes available for a topic. The right hand column offers some guidance on how to get started with each purpose.

Sara shows us a model of her own writing. She splits her favorite topic (dogs!) into the six purposes. Each purpose contains at least three topics about dogs. Yet another successful example of the basic guided release model (teacher walks the class through an already completed/in process example to show basically show students what to do. Then students are encouraged to do their own). Now it’s our turn to do the same! Here’s my example. I didn’t finish it in time. Sorry about the poor lighting.

We share out. It’s amazing what a wealth of information can come from just a single topic! Even if some of my/out ideas don’t fit squarely into each category, that doesn’t matter. What matters is generating tons of student-centered ideas from a single student-centered topic. The classroom is crackling with ideas and laughter.

I can’t wait to use this in my class this year. She ends up with a list of resources.

Multigenre Presentations and Metacognitive Thinking – NVWP Summer ISI – Day 5

Welcome to the Northern Virginia Writing Project’s 2016 Invitational Summer Institute! I’ll be blogging the demonstration lessons and the various activities occurring during our four-week duration. Find out more about the NVWP and the National Writing Project.

M&Ms: Multigenre Presentations and Metacognitive Thinking

Kyle’s presentation deals with multigenre writing. For anyone unfamiliar with multigenre writing, the following infographics should help. Multigenre writing is exactly what it sounds like: a piece or collection of pieces drawing from the characteristics and styles of more than one genre. Tom Romano is the name most associated with multigenre writing.

Kyle’s presentation begins with disengagement. He noticed that many of his students wrote stagnant, repetitive, and formulaic compositions. So he began allowing students to create really any sort of object in response to their reading. While students appeared engaged (who wouldn’t be when your teacher lets you bake a cake for an assignment?), Kyle realized the students weren’t pushing and stretching themselves in terms of writing. Kyle offers the following reasons to explain why he chose multigenre writing as a classroom problem to explore:

Quickwrite Prompt: What is genre? What is style?

Genre is a socially agreed upon set of stylistic conventions unique to a particular type of text. Style. Hmm. This one is tougher. Style is the result of the various techniques consistently employed by an author. Syntax, mood, tone, point of view, etc.

We share out. A partner says genre is the ‘what’ and style is the ‘how.’ I like this. Someone else says style is the manifestation of voice. Content and style have a symbiotic relationship informing each other. Kyle says that when we talk about multigenre we have a tendency to get hung up on just the genre component. We’re also talking about differences in style and form as well as genre.

Quickwrite: Write as many genres of writing as you know in 45 seconds!

Historical fiction – sci fi – romance – young adult – fan fiction – bio/autobio – fantasy – folktales – personal narrative – essay – nonfiction – poetry – epistolary – tweets / blogs – profiles – academic writing – graphic novels – drama – songs – dystopian – (I added these last few after listening to my awesome partners)

We list like a billion of them. I bolded the ones I like to write in the most. It’s not necessarily that I like these genres more, actually; it’s that these are the genres I’m most comfortable writing in. I think I need to stretch myself more. Someone else says that the genres they enjoy reading the most are the ones they don’t want to write. I can identify with that statement. I LOVE reading fiction but I never write it.

We must write everything we ask our students to write, by the way. This is an important component not only of the Writing Project but also one of the few things that could probably be considered ‘best practices.‘ Helping students write free verse poetry without having struggled through writing it myself isn’t effective.

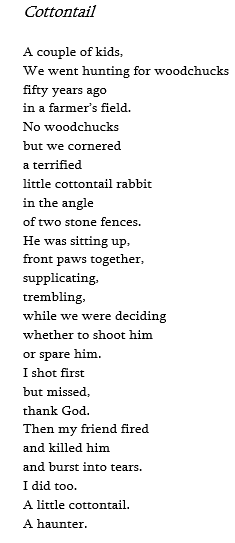

Next we read and annotate Cottontail by George Bogin:

We all annotated for different things: figurative language, transition words, participials, beginnings and endings of lines, polysemy, etc. Next Kyle asks us to showcase one of the author’s move by writing about it in a different genre. Like writing an op-ed about the state of gun control. Let’s give this a shot.

Want Ad:

Wanted: Vocabulary averse author looking for parts of speech to help spruce up a poem. Please respond ASAP as situation is extremely dire.

Response: Dear Sir, I write to you in response to your want ad. After pontificating upon your desire I sat down to pen this response, shaking as I am from the potential responsibility involved in writing this missive. I’m frequently called upon to decorate, traipsing through text, illuminating meanings, improving diction.

I tried to highlight the author’s use of participials in this want ad. Others wrote op-eds about childhood trauma and etc. This is a difficult assignment, but it’s a good type of difficulty. Heads are steaming and teeth are gnashing in the best way.

The final part of Kyle’s lesson involves us writing a multigenre response to Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been by Joyce Carol Oates. Choose a thesis or literary theory with which to explore the text. Then using that as a lens, create five different works (genre and/or style) to analyze the text. This task requires manipulating and applying several knowledge bases.

OK. Maybe I can view this story through the lens of process pedagogy. Let’s see if I can reduce this story to a series of stages involving the continuous refinement and growing of an idea through the iterative and recursive process of writing. I’ll also switch the perspective to focus on Friend instead of Connie (BTW the following won’t make sense unless you’ve read the short story. Which you should because it’s amazing and super creepy). This lens could work because Friend has to revise his approach a number of times in response to his audience (Connie). He’s making rhetorical moves to achieve his purpose.

–Prewriting: Friend sees Connie at the movie theater. The idea is born.

–Drafting: Friend visits Connie at her home and asks her to come with him.

–Revising: Sensing Connie’s reticence, Friend revises his approach to include implications of violence against Connie’s family.

–Editing: Watching Connie start to ‘break,’ Friend edits, polishes, and refines his revised approach of violence by widening the scope to include violence against not only Connie’s family but her house and her own life.

–Publishing: Friend’s rhetorical moves are successful and Connie comes out to meet him.Although Friend hasn’t necessarily ‘grown‘ his idea,

Whew! That was tough to do in only a short amount of time. Multigenre thinking is powerful stuff, because it forces the brain to break down something, understand the way parts contribute to a whole, and then apply that understanding to a new object, an object with its own rules and contexts. There’s a lot of opportunity to get something wrong in this process, but that’s a good thing. Teachers must develop a more nuanced understanding of error as concomitant to growth. Time for a break!

Know Your Theory! – Process Composition Pedagogy Edition

This series of blog posts will provide an overview of the composition field’s relevant pedagogies. These posts will draw mainly upon A Guide to Composition Pedagogies by Gary Tate et. al. The book is divided into chapters based on the different pedagogies. The breakdown for each post will be around 1/2 summary and 1/2 my own reflections, analysis, anecdotes, and commentary. Although I’m writing these posts to help myself process through and reflect upon the field of composition, it’s my hope that any teacher of writing can find something of interest. Part 1 addresses collaborative writing pedagogy, part 2 explores critical pedagogy in the writing classroom, part 3 describes expressivist composition theory, part 4 examines feminist composition pedagogy, part 5 concerns genre composition pedagogy, and part 6 looks at literature composition pedagogy.

Process Composition Pedagogy

I write in a scattershot format. I start out by writing out key concepts and interesting phrases on a blank document. Then I flesh out each concept, move things around, and try to let a structure reveal itself. My goal is to expand each concept and idea until it organically dovetails with what comes before and after. This requires a lot of hemming and hawing, indecision, and general consternation. At the bottom of each document I keep a “Misc. Ideas” section where I dump seemingly random thoughts. By the end my hope is that each paragraph and section successfully bleeds into the next, creating a narrative thread that ferries the reader along from point to point. I didn’t realize this until someone asked me to describe my personal writing process. With that in mind, this final post in the Know Your Theory! series describes process pedagogy. How do writers write?

I could reduce every composition theory explored in this series to a value statement. For example feminist composition pedagogy uses writing to address and achieve social justice in the classroom. Genre pedagogues bring attention to the different ways genre shapes our perception of and interaction with various forms of literacy. Each links writing with a goal larger than the writing itself. This is not the case with process pedagogy. Process pedagogy uses knowledge about how students write in order to improve student writing; writing is both the subject and the object. The idea behind process pedagogy is simple to understand: focusing on how we write improves what we write. The simplicity of the idea belies the semi-radical nature of process pedagogy. In order to understand that we need a glimpse of what was happening on the composition scene before the process movement kicked off.

The Spectre of Traditionalism

As an inner categorizer, my natural inclination is to reduce everything to discrete units so I can slot them into the appropriate categories. I also have a penchant for periodization. Many of my frustrations about trying to understand the composition field stem from my (and the field in general’s) inability to offer up a formalized chronology of major events. Even if I could cobble together some sort of linear history, the sequential logic of A -> B -> C ignores the complex vertical negotiations between institutions and teachers that bubbles and froths below any orderly history.

Ever since its beginnings at a Dartmouth College Seminar in 1966, process pedagogy has loomed large over the field of composition. It offered an appealing challenge to current-traditionalism, the dominant paradigm of composition instruction at the time. In order to understand the widespread appeal of process pedagogy, it’s first necessary to explore the methods of current-traditional instruction. My writing about current-traditionalism is in the present tense because it still lives on in many classrooms across the country. I say this not to disparage teachers but to point out that what we do in our classrooms often borrows from different bodies of theory at different times. Restricting yourself to a single theory is myopic and limits your ability to reach a diverse population of learners.

Current-traditionalism (CT), called so because it brings traditional beliefs into current classrooms, is defined as “formulaic notions of arrangements; an inflated concern with usage and style…no discussion of drafting, and a focus on grammatical and mechanical correctness.” Students in a CT classroom can expect to practice writing in the dominant modes of expository, descriptive, narrative, and argumentative. In terms of assessment and end goals, CT measures student writing against well-established pieces of professional writing. Compared to professional and published writing, student compositions naturally come up short. Since CT views writing as the combination of parts (thesis statement, topic sentences, concluding sentences) and axiomatic rules (avoid sentence fragments, watch out for comma splices, don’t split infinitives), creating a polished piece of writing means attending to the mechanics and usage of established grammar and genre.

A CT approach views writing as an assemblage of knowable parts. Take the paragraph, for instance. Current-traditionalism borrows its definition of the form and function of a paragraph from Alexander Bain’s seminar paragraph definition of 1866. Don’t be fooled by the archaic date and unfamiliar name; Bain’s definition of the perfect paragraph continues to hold sway. The picture below is a page from one of the many writing textbooks in my school’s English rooms (Write Source: A Guide for Writing, Thinking, and Learning).

Paragraphs should be written as mini composition in which every sentence must fall under dominion of the powerful and guiding introductory topic sentence. I mention the paragraph for two reasons: to highlight the ways current-traditionalism lives on in English classrooms and to provide a minor peak into the world of English textbooks (For a fascinating look into the ways textbooks have influenced English check out Textbooks and the Evolution of a Discipline by Robert J. Connors).

Much like every other composition pedagogy I’ve covered throughout this series of posts, current-traditional pedagogy is no one thing. It’s marked by the struggle “between stasis and change” that characterizes all pedagogy. Mentioning CT’s status as a pedagogy-in-flux is important because it’s often viewed as a calcified set of beliefs and practices which no longer serve any instructional value. It’s also worth noting that teachers who employ pieces of current-traditional pedagogy are certainly not “bad” teachers. The more I learn about composition studies, the easier it is to understand why many K-12 English Language Arts teachers implement a variety of writing strategies, some in contradiction with each other.

From Product to Process

The above image (from A Guide to Composition Pedagogies by Gary Tate et. al.) sums up the changes between current-traditionalism and process composition. The ideological assumptions behind the process approach “represented an important shift in priorities, attitudes, and the use of class time.” Process pedagogy places a focus on the process of writing, on the various methods and strategies real writers employ to create a piece of writing. We’ve already discussed a few reasons why this change was so monumental.

Early process approach split the writing process into three main components. Donald Murray’s landmark essay Teach Writing as a Process, Not Product suggested the tripartite structure of prewriting, drafting, and revising that continues to hold sway today. While certainly not new (classical rhetoric’s five-part canon includes invention and arrangement), spending instructional time on prewriting and content generation before drafting was an important break from tradition.

The rise of process pedagogy paralleled newfound interest in the composing process of the student writer. Educators like Janet Emig, (The Composing Processes of Twelfth Graders), Nancy Sommers (Revision Strategies of Student Writers and Experienced Adult Writers), and Muriel Harris (Composing Behaviors of One- and Multi-Draft Writers) produced groundbreaking scholarship investigating the ins and outs of the composition process. How do students approach a new piece of writing? How do they move between writing process stages? How do the moves made by students and expert writers compare? Thanks to these and other efforts, we know that good writing requires copious amounts of revision, and that beginning writers spend the least amount of time on revising and editing. Process scholars have also helped illuminate the complex situational variables that inform how a student approaches a piece of writing. Location, purpose, audience, genre, and mindset are just a few of the factors that affect student writing. The fact that these ideas may seem obvious to us now is a testament to the near hegemonic influence of the process pedagogy movement.

Criticism and Push-Back

As with all schools of theory, early incarnations of process pedagogy were refined and rebalanced by academics and practitioner-scholars. Many of us might remember (or use) some form of a process wheel in our classes. We now know that there is no one process. Expecting students to move from prewrite to publish in a linear fashion misses much of the point of process pedagogy. For this reason later theorists stressed the recursive nature of writing.

Composition’s social turn, a move in the late 1980s/early 1990s to reorient the field to include issues of culture, ideology, and sociality, reminded compositionists that when it comes to writing, culture matters. Any effective English teacher must account for cultural differences in how children, families, and schools when planning for student writing. In Other People’s Children, Lisa Delpit offers a scathing critique of progressive teachers who engage children in peer critique and brainstorming while ignoring direct skills. Her book is a poignant reminder of the importance of a balanced approach to literacy.

Chances are if you teach English you’re familiar with some process pedagogy. Major education publishing houses like Heinemann produce scads of professional materials devoted to helping children flesh out ideas, revise drafts, and edit for standard grammar and punctuation. That’s why I’ve left the actual classroom component of this post until the end. I wanted to contrast process pedagogy with current-traditionalism because I think there’s incredible value in understanding where we come from.

This is my final post in the Know Your Theory! blog series, and I hope you’ve enjoyed reading them.

Additional Resources Consulted:

Current-Traditional Rhetoric: Thirty Years of Writing with a Purpose by Robert J. Connors

Process Pedagogy by Lad Tobin

Coherence in Paragraph-Level Structures by Marc Pressley

Know Your Theory! – Literature and Composition Pedagogy Edition

This series of blog posts will provide an overview of the composition field’s relevant pedagogies. These posts will draw mainly upon A Guide to Composition Pedagogies by Gary Tate et. al. The book is divided into chapters based on the different pedagogies. The breakdown for each post will be around 1/2 summary and 1/2 my own reflections, analysis, anecdotes, and commentary. Although I’m writing these posts to help myself process through and reflect upon the field of composition, it’s my hope that any teacher of writing can find something of interest. Part 1 addresses collaborative writing pedagogy, part 2 explores critical pedagogy in the writing classroom, part 3 describes expressivist composition theory, part 4 examines feminist composition pedagogy, and part 5 concerns genre composition pedagogy.

Literature and Composition Pedagogy

Last year a colleague of mine asked me to define the purpose of English. What is the essence of the discipline? What is its content? I fumbled for an answer. On a basic level students in my class read and write. They analyze texts, investigate language, and use literacy to interrogate themselves and their world. Yet other disciplines could claim the same basic objectives. In social studies, for instance, students use similar techniques to explore history and understand the push and pull of civilizations. So what makes English unique?

Anytime I tell someone what I do for a living, they invariably ask me about the books we’re reading. What novels do I ask children to read these days? I tell them that my classes don’t take part in too many whole-class novel units (Practitioner-scholars like Donalyn Miller and Penny Kittle have helped cement the notion of student choice as a dominant theme in secondary English classrooms across the country). If you’re not reading William Faulkner, George Orwell, or any of the other white male authors from the canon, what do you all do in class?

We read and write. Literature and composition share a complex history together. The contentious relationship between the two deals with fundamental issues of literacy, education, and democracy. Your employment of literature in the classroom depends upon how you answer bedrock questions about the connection between curriculum and society.

Debates over curriculum and education’s purpose have been around in earnest since at least the Common School movement of the mid 19th century. Humanists wanted a classical education of Greek, Latin, and belles lettres. Social efficiency educators pushed for streamlined coursework in order to match up school curriculum with the skills demanded by employers. Progressives wanted school to prepare kids to be citizens, revolutionaries, and public servants. Literature can transform itself to meet any of these diverse needs.

But that’s not what this post is about. It’s about how teachers have struggled with integrating reading and writing for over 200 years. Unpacking the relationship between composition and literature benefits from a basic understanding of the growth of English as a discipline.

Up until the late 1800s there was no English. Universities offered rhetoric/oratory (speech) and belles lettres (literature studied for its aesthetic appreciation). 18th and 19th century academia was firmly situated within an oral culture. Although students were required to write, their compositions were to be memorized and delivered before the class. Writing was rarely taken beyond a rough draft. Students wrote only as preparation for the main event of presenting a beautiful and eloquent oration.

Charles Eliot, Harvard’s president during the late 19th century, introduced a system of electives that dethroned the dominant standardized university curriculum. Schools began offering different courses for students. As new courses opened up others receeded. The birth of English coincides with the downfall of certain higher education stalwarts such as Greek and Latin. As the influence of humanist curricula (Greek, Latin, the ‘classics’) continued to wane in the late 18th century, English rose to prominence as a new mainstay of the higher ed experience.

In time oratory lost its belletristic flourishes and became rhetoric. Rhetoric “gradually lost its oral emphasis, finally giving way to the exclusively written focus of English composition.” Now bereft of the traditional focus on oration, new composition classes needed something to study. So students began producing early literary criticism. Courses in literature moved towards the canon, employing literature as a high-brow product fit only for those pursuing a life of the mind.

By the early to mid 20th century, English departments were split between the study of literature and the teaching of writing. The legacy of separation and distinct curricular spheres for reading and writing remains potent in English classrooms today.

In a previous post I mentioned how it took 15 years for feminism to move from academia into composition classrooms. A similar case might be made for the relationship between composition courses and English Language Arts classes at the secondary level. Although anecdotal, I would offer that secondary teachers often privilege reading over writing. When writing is taught, it’s often approached through the lens of writing for high stakes tests. Test writing is a legitimate genre with its own conventions and forms. The fact that testing ends up narrowing the English Language Arts curriculum his should come as no surprise to anyone familiar with public education.

I think it’s fair to make the modest assertion that we are in the beginnings of a lit/comp renaissance. The rise of the mentor movement in secondary education offers English teachers an effective way to combine literature and composition. By mentor movement I mean the proliferation of books, websites, and articles focused on mentor texts. Popular practitioner-scholars are bringing renewed attention to the benefits of integration. Combine this with our 21st century understanding of a text as essentially any cultural artifact and you have new crops of teachers helping students read as writers, dissecting the moves authors make in order to enact them in their own compositions.

It’s my hope that the mentor movement, in tandem with what we know about textual artifacts from Cultural Studies, Genre Pedagogy, and Critical Pedagogy, will help students both analyze and create works of real power and meaning.

Know Your Theory! – Genre Composition Pedagogy Edition

This series of blog posts will provide an overview of the composition field’s relevant pedagogies. These posts will draw mainly upon A Guide to Composition Pedagogies by Gary Tate et. al. The book is divided into chapters based on the different pedagogies. The breakdown for each post will be around 1/2 summary and 1/2 my own reflections, analysis, anecdotes, and commentary. Although I’m writing these posts to help myself process through and reflect upon the field of composition, it’s my hope that any teacher of writing can find something of interest. Part 1 addresses collaborative writing pedagogy, part 2 explores critical pedagogy in the writing classroom, part 3 describes expressivist composition theory, and part 4 examines feminist composition pedagogy.

Genre Composition Pedagogy

In a piece of historical fiction an author sets an imaginary plot against a specific historical setting. Realistic fiction involves characters and conflicts that could have actually occurred. Autobiography is someone’s factual telling of their own life story. At the middle school level this is how I’ve taught genre. However, contemporary understanding sees genres as rhetorical acts situated in specific contexts rather than a static set of conventions for students to memorize and mindlessly employ.

Carolyn Miller’s 1984 influential article “Genre as Social Action” defines genre as “rhetorical actions based in recurrent situations.” Authors, faced with similar writing tasks (recurrent situations), make similar stylistic and formal decisions (rhetorical actions). Over time readers come to recognize and expect certain conventions in a certain genre. For example I wouldn’t expect an autobiography to include a chapter on the author’s experiences transforming from a human into a mythical creature. A magical transformation goes against autobiography’s social contract as a genre rooted in the real. When teachers help students understand genre as rhetorical action they help students navigate the cultural expectations of public writing. To understand how a genre works is to gain access to the socially accepted forms of expression and discourse.

Three Broad Pedagogical Approaches to Genre Composition

As with the other composition pedagogies in this series, genre pedagogy has no one true way. The chapter breaks down genre pedagogy into the three following methods.

1. Teaching Particular Genres

2. Teaching Genre Awareness

3. Teaching Genre Critique

These three methods are not mutually exclusive. Incorporating all three approaches in a classroom creates students who are empowered to act rhetorically “within and beyond the situations they will encounter throughout their lives.”

Teaching Particular Genres

Giving students the tools to identify the characteristics of various genres is perhaps the most obvious and common method for teaching genre. Students learn a genre in order to write it. The genres we teach speak to perspectives we privilege in the classroom. Deborah Dean notes that the “genres we select favor and develop certain perspectives more than others.” For instance, Dean explains that focusing on five-paragraph essays promotes a certain type of logic, distance, and formality. Teaching mainly personal narratives favors individualism and chronological thinking.

Teaching students about genre characteristics often requires the use of explicit instruction. Although some warn against the use of direct instruction, the authors note that teaching students skills in an explicit manner doesn’t have to be formulaic or rote. Other scholars such as Ken Hyland and Lisa Delpit argue that explicit instruction in genre conventions is essential for supporting and empowering certain population groups like second language learners.

Teaching Genre Awareness

If teaching particular genres seeks to introduce students into the public arena of literacy, another genre pedagogy, genre awareness, seeks to provide students with techniques for learning any genre. Genre awareness pedagogy “treats genres as meaningful social actions, with formal features as the visible traces of shared perceptions.” A genre awareness approach requires students to collect samples of the genre, identify the larger context and rhetorical situation in which the genre is used, identify patterns in content and form, and analyze what these patterns reveal about the situation and larger context surrounding the genre. Once learned, students can apply the genre awareness approach to learning any genre.

Sample assignments include asking students to analyze a genre and then create a “mini-manual” to instruct others on how to read/write that genre. Sarah Andrew-Vaughan and Cathy Fleischer have developed the Unfamiliar Genre Project. The assignment cycle requires students to select an interesting genre, collect representative samples of it, keep a research journal, write their own version of it, and more.

Teaching genre awareness attends to genre’s ideological and social contexts as well as its rhetorical and textual features. The goal of the process is to develop within students a nuanced and rigorous understanding of “how, why, and for whom” they write. Students use pieces of writing as objects of genre analysis. Helping students see writing samples as objects for strategic analysis instead of models for emulating requires a significant time commitment. In her book Scenes of Writing: Strategies for Composing with Genres, Amy Devitt recommends helping students gain access to social situations, develop interview skills, and make observations. This is a far cry from telling students why Ender’s Game is an example of science fiction.

Teaching Genre Critique

True to its name, genre critique seeks to train students to think critically about existing genres in their cultures. The ability to analyze a genre brings with it the ability to “subvert, legitimize, or revise” them. Genre critique fits squarely within the larger tradition of critical pedagogy by calling attention to the way every day cultural practices often constitute various systems of oppression.

Genre scholars Richard Coe and Anne Freedman use the following meta-rhetorical questions to help students tease out the ideological implications tangled up within genres:

1. What sorts of communication does the genre encourage? What sorts does it constrain?

2. Who can – and who cannot – use this genre? Does it empower some while silencing others?

3. What values and beliefs are instantiated within this set of practices?

4. What are the political and ethical implications of the rhetorical situation constructed, persona embodied, audience invoked, and context of situation assumed by a particular genre?

Students learning this type of critique pick apart a genre, analyzing it for roles and expectations in order to create a new piece of writing that violates that genre’s tenets. The authors give the example of a syllabus. What roles for students and teacher does a traditional syllabus enact? How could students remix this genre to subvert the positions of power implied within a formal syllabus?

In “Genre, Antigenre, and Reinventing the Forms of Conceptualization,” Brad Peters says that the goal of genre critique is for students “to acquire – rather than acquiesce to – the grammar of a genre.” Taking a page from Cultural Studies, this type of perspective treats the genre as a cultural artifact ripe for analysis. For instance what can a food label tell us about how our culture views issues of consumption, transparency, and government regulation? A pedagogy of genre critique teaches genre not to help students internalize characteristics but to show what forms of discourse are possible. Genres “create an opening for students to realize that what has always been is not what must always be.”

Wrapping Up

I’ve always taught genre as a set of criteria for students to memorize. As I’ve grown as an English teacher (and read authors like Katie Wood Ray) I’ve induced students to explore a genre through an inquiry-based approach rather than a transmission model. I now understand the power embedded within and enacted by genres. Next year I’m looking forward to helping students investigate shared understandings and create their own meanings by applying a more robust understanding of genre pedagogy.

I read so you don’t have to: Katie Wood Ray’s ‘Study Driven’ – Part 1, Groundwork for an Inquiry Approach

Study Driven: A Framework for Planning Units of Study in the Writing Workshop

Katie Wood Ray

TL;DR:In this book, Katie Wood Ray lays out a complete vision for implementing an Inquiry-based approach to writing. The study driven framework grounds student writing in real-world examples. Student discourse becomes the curriculum. The following chart summarizes KWR’s five-step approach to an inquiry method. Students read authentic writing, determine what makes each genre tick, then write under the influence of the genre.

I will explore and summarize the book throughout two blog posts. Part 1 lays the ground work. Part 2 goes through the process.

Chapter 1: Introduction

Framing writing instruction as ‘study’ represents an inquiry-based stance to teaching and learning. An inquiry stance repositions curriculum as the outcome of instruction rather than the starting point. In this particular set of practices, the students’ noticing and questioning around the gathered texts determine what will become important content in the study (the teacher doesn’t determine this in advance), and depth rather than coverage is the driving force in the development of this content.

Although this idea of “uncovering curriculum” isn’t new, it takes on heightened significance in an age when school districts expect teachers to map out dense scope-and-sequence plans and curriculum maps before children even enter the building after Summer Break.

Student responses to teacher questions aren’t just filler to provide a moment of engagement before the teacher tells the students what they should actually think. The teacher is obligated to do something with student responses. They are the important stuff, not the way to get to the important stuff. There is no content until the children start talking. There is no study without the students.

Chapter 2: Making a Case for Inquiry Study

This chapter explores a few popular alternatives to teaching from an inquiry stance.

-Guided practice: Use school-world examples of writing. First, teachers give a generic definition of the kind of writing they want students to be doing. Then, the teacher gives the students a graphic organizer or two to use when creating this type of writing. The teacher next models an example, writing a piece to lead her students. Lastly, students are let loose to write their own.

-Partial inquiry: Use real-world examples of writing. But instead of studying the texts with students, teachers would have previously planned out where they wanted to go with each text. This model allows teachers to plan units of study ahead of time for use in their own class or someone else’s. I’m reminded of the standardization work many counties expect from their teachers. In my county, for example, teachers use PLCs to create common end goals for a given unit.

-Lesson-Delivery: Traditional. Teachers assign writing for students to complete, turn in, and get back with a grade. There is no study or learning in this stance, simply mindless compliance. Teachers often ground this type of writing in “mythrules,” those desiccated writing rules that don’t really exist outside of a classroom setting. For instance, every paragraph in a piece of expository writing must begin with a main idea/topic sentences. This part-to-whole orientation provides teachers with a sense of comfort and control. Managing a classroom becomes much easier when you know exactly what everyone should be doing ahead of time.

-Study-Driven Inquiry: KWR posits that an inquiry stance is better than these other forms of instruction. It teaches students about the particular genre or writing issue that is the focus of the study, and also to use the same habits of mind experienced writers use all the time. They teach them how to read like writers. Instruction is grounded in how texts actually function and how authors really use words.

Big Shift – What role should modeling play?

Teacher modeling is an essential component to writing instruction. Teachers often use model more in the noun sense than in the verb sense. They want their writing to serve as a model for what the students will write. An Inquiry stance, on the other hand, uses real-world texts as the examples. This allows teachers to model the process, not just the creation. Teachers can make their thinking public about what decisions they’re making, the how and the why and the where of the writing process. Students learn to write from reading rather than teaching.

Closing thoughts on teaching from an inquiry stance:

-asks students to read like writers, developing a habit of mind that will potentially teach them how to write well throughout their lives

-ensures that the content for writing is grounded in realities of both the writing process and product

-expands the teacher’s knowledge base

-helps students develop a guiding vision for writing before they engage in revision

-asks the teacher to model the process, not the product

“When what you know about ‘people who write’ becomes what you know ‘as a person who writes,’ what you know changes.” (32)

Chapter 3: Before Revision, Vision

This chapter makes a case for helping students develop a vision for their writing.

Students should always be able to answer the question, ‘What have you read that is like what you are trying to write?’ For purposeful revision to take place, students must have a clear vision of what they want to accomplish in the first place. The content that each writer decides to pursue can be individual, but the vision for the piece comes from the larger world of writing. Students should look at a range of kinds of writing they can do inside a particular mode or genre and then decide what kind of article they want to write.

Before vision, intention:

One of the key responsibilities of the writing teacher, therefore, is to help each student develop intentions as writers. This means developing purpose, passion, and reason to write something.

This leads to a tension: whole class genre study forces the intention to come from the vision of a kind of writing, and not the other way around. This is important. KWR accepts this tension, however, for two reasons. First, the tension is grounded in the reality of some writers’ real world experiences. Many authors must meet deadlines and create different types of pieces that start from somewhere else other than within. Second, genre study exposes students to the wide variety of writing that exists in the outside world. Genre study helps students fulfill intentions they might not have known existed in the first place.

“Units of study other than genre (like one on punctuation) should therefore be carefully folded into the year.” (54)

Chapter 4: Understanding the Difference between Mode and Genre

This chapter explains how to use ‘mode’ and ‘genre’ to help students compose meaningful pieces.

Modes describe the meaning work that a writer is doing in a text. They come from the influence of traditional studies in rhetoric. Genre is the thing people actually make with writing.

If there are clearly defined and professionally accepted labels for the kinds of writing teachers want from their students, use them. But this often isn’t the case. Don’t shy away from certain kinds of writing because you don’t know what to label it. As long as you can gather a stack of texts fulfilling similar intentions, then you’re good. Let the definition come from the characteristics those texts share. Clarity of vision comes when writers say as much as they can to describe the kind of writing they have in mind.

Different Modes at Work (within the same text)

Authors often use several modes in a single piece of text to accomplish their purpose. Most pieces, regardless of the genre, switch off between description, persuasion, narration, and exposition. KWR states that although this might be commonly understood, schools have a tendency to gloss over complexity of modes within a single text. KWR argues that this oversimplified notion of mode is detrimental to curriculum.

The fix is simple: use genre (instead of mode) as the point of departure for a piece of writing. So instead of teaching students to do persuasive writing and descriptive writing, have students write opinion pieces and book reviews and novels and commentary. Know what kind of thing you want students to write, then show it to them. So, start with genre.

“The thing to remember is that mode is a descriptive device, not a prescriptive one.” (61)

Part 2 coming tomorrow! Thanks for reading.

Implementing Multi-Genre Research Projects with Technology – NVWP Summer Institute – Day 13 pt. 1

Our final week! We are bummed.

Our first presentation is Diane Myers.

Multi-Genre Research Projects

She gets us moving with a Four Corners activity: how has research changed over the years for you professionally or personally?

We move to a corner of the room corresponding to our grade level.

Our middle-school group talks about the challenges of research in the 21st century. As teachers we often struggle with how to handle research in a way that honors both the analog world (books, libraries) and the digital world (databases, boolean searches).

We then share out whole group. Some of us mention that the nature of the research project matters greatly. Since a research paper has so many components within it (indexing, searching, skimming, bibliographies, citations, MLA/APA style, etc.) that the actual research/learning often gets lost. Is this source reliable? Is this article credible? My neighbor mentions how important it can be to give the students the information that they need to help them research vs. making them do every single part. Many of us have great relationships with librarians.

Diane is going to talk to us about the final step of the research project. The communication of information. When we think about what we want our children to learn, the communication of information is pretty important. She sends us to Padlet. (A free app/website) Padlet is a great place to share information with a larger audience. Sort of like a Google document only more visual. Everyone has their own space and students can’t mess with each other’s typing.

Here is Our NVWP Padlet and a pic of our thoughts on ‘What does research writing look like in your classroom?’

All you do is double-click anywhere and start typing in your box. And in each box you get to insert links, images, videos, etc. Diane uses Padlet for many things including homework. In the following pic students did their homework, took a picture of it with their iPad, then posted it on a Padlet Diane set up.

OK. So, what is a multi-genre paper?

–It arises from research, experience, and imagination.

–Composed of many genres and subgenres, each piece is self-contained, making a point of its own, yet connected by a theme or topic and sometimes by language, images, and content.

–It is not an uninterrupted, expository monologue nor a seemless narrative nor a collection of poems

–May contain many voices, not just the author’s.

How is a multi-genre paper different?

What are multi-genre artifacts?

–Print Media: profile, news article, loetter to the editor, editorial

–Visuals with Words: posters, ads, geeting cards, word clouds, emblem, timeline

–Visual Display: art work, map, collage, artifacts for time capsule

–Informational: quiz, recipes, menus, how to, charts, biographies, encyclopedia entry

–Narrative: story, memory, eyewitness account, narrative poem or ballad

–Poetry: found poem, bio poem, haiku, free verse, song lyrics

–Performance: podcast, public service announcement, dance, puppet show, video, speech

How exciting is this list of possible products, right? When we think about keeping education relevant to the 21st century (which can be a tricky phrase if used as a Trojan Horse to sneak in useless corporate software into schools), the isolation of the lone research project comes to mind as an aging artifact. With so many options, kids have no choice but to find something that’s both challenging and engaging (with our help, of course!)

Diane takes a minute to tell us about Tom Romano. Most credit his book Blending Genre, Altering Style with kicking off the multi-genre project. There are tons of resources online about this, as well.

When it came time for students to share their multi-genre research projects, she had each student make their own QR code that linked to their Padlet.

So, students had an empathy unit where they investigated topics such as post-traumatic stress disorder, dyslexia, ADHD, biploar, etc. They then created research notes using Easybib, a free program that helps students organize research, create notes, paraphrase, create bibliographies, etc. Then they export it to Google! When I think about the power of technology in the class, I think about how it renders obsolete many of the small tasks we adults associate with classroom tedium. Bibliographies, where the comma goes, etc. As superintendent Josh Starr said, if you can Google it, why teach it?

She then has them fill out a graphic organizer in Google Docs. She uses Google Classroom to do pretty much everything. “Here’s the assignment, here’s the rubric, here’s where you turn it in.”

Here’s what a student example looks like:

Each hyperlink in the table of contents takes you to the particular assignment which is in Google Docs or Google Slides. At this point the collective jaws of the room are on the floor.

Diane then brings us to the big daddy of classroom tools: www.classtools.net. This site has all sorts of amazing ways to let kids take advantage of technology in a controllable format. SMS generators to make student made text message conversations look authentic, Fakebook pages, video game screens, etc. You must check out this site.

Now we get to try! DIane passes out a fact sheet she’s made for the sake of this presentation with information about mental health conditions. Then, she gives us our multi-genre artifacts. My partner and I had to create a recipe for Generalized Anxiety Disorder.

Here is our product:

Diane tells us you can differentiate by having some of the genre artifact planning pages have sentence starters. We share out. THEY ARE AMAZING. Advice letters about kids with ADHD. I Am poems about Autism. Absolutely fantastic work, Diane!

Teaching Persuasive Writing through Op-Ed Genre Study: NVWP Summer Institute – Day 9 pt. 1

Our first demo lesson is Amy Carroll.

Finding Your Passion: Teaching Argument through Op-Ed Genre Study

Amy begins talking about how her school handled writing instruction in an overly prescriptive way. Some call this TEEEC (topic, evidence, conclusion), the hamburger paragraph, the Jane Schaffer program, or, in Amy’s case, the Proper Paragraph format. Standardized and rationalized. Many heads nod in our room. We’ve all experienced this in some form or another. This sort of 5-paragraph didacticism is often coupled with groans and moans about how today’s students can’t write. There is a definite relationship between these two ideas. Now isn’t the time to suss it out. Amy decided to go rogue and immerse the kids in a genre study using op-eds. A proactive vs. reactive approach.

She gets us writing with a quickwrite:

Q1: What do you think when you hear the words “persuasive essay”? What are some topics of persuasive essays that you have written in the past?

So, I sort of have to sit and think about this one. Normally I can unleash my inner logorrhea at a moment’s notice when it comes to these things. So, what is it about persuasive writing that stymies me? I didn’t have my students do really any persuasive writing last year, now that I think about it. As freshly-awakened teacher, I didn’t want to do anything that reeked of traditional school writing. Traditional school writing, to me, is a prompt about whether or not students should wear uniforms. Or if cell-phones should be allowed in schools. Of topic, evidence, connection, conclusion. Inauthentic statements written for nonexistent audiences. I associate persuasive writing with the kind of anemic, formulaic composition I wanted to get away from. This is, of course, not really true, Anything can be exciting; it’s all about how you approach it. So, I’m looking forward to hearing about how to use persuasive writing in an exciting way. That last sentence definitely reads as a conclusion but we’re still going, so I need to type more. It’s hard just riffing on something! Ok, that’s it.

Then we turn and share with our partners. My neighbor has a slightly different take. She remembers the feeling of excitement when a teacher gave her the assignment of writing about whether or not her school should teach a particular book. She also says that all writing is persuasive in a way. We share out to the whole class. We’ve all assigned the cell-phone/uniform topics, probably because we thought they would be interesting! Others share out their own experiences as a student with persuasive writing. Some talk about persuasive writing as a tool of autonomy for students. Some of us talk about how these prompts lead students to write what they think the teacher wants to hear. Or that much persuasive writing forces us into false dichotomies. Is X good or bad? A sort of all-or-nothing thinking that severely limits the scope of dialogue.

Amy uses Edmodo, btw. She talks to us about living a paper-free life. I must admit, I’m currently incapable of thinking rationally about education technology. Ever since I started reading Audrey Watter’s blog, I have a knee-jerk reaction to ed tech. This is another example of how naive my understanding is of, like, everything. I have to progress through this naivete before I’m capable of thinking about technology in the classroom in an un-extreme way.

She recommends using Law and Order episodes to help teach introductions and conclusions. Amazing.

Amy talks to us about Reading Like A Reader vs. Reading Like A Writer. Reading with a sense of possibility, a sense of “What do I see here that might work for me in my writing?” I’m reminded of Stephen King’s admonition that the only way to become a better writer is to read more. Obvious tie-ins with the segregated way we typically approach reading and writing. As separate beasts, never the twain shall meet. I hear “read like a writer” often, but rarely do I hear “write like a reader.”

Amy passes out the model text for today’s demo lesson, a NYTimes piece about vaccines, Disneyland, and Measles. This is standard operating procedure. A whole-group read aloud without purpose for the first run. Just to get into the rhythm of the piece. The language. Read through the piece first. Then, read it as a writer. What do you notice about the sentence structure? The punctuation? The organization? We talk aloud through the ‘Reading like a reader’ questions. What is happening in the piece? Who is involved? What conflicts, if any, are presented? What info am I getting in this piece? A set of questions to really help us get our feet wet and wade into the article.

Then we move into ‘Reading like a writer.’ She projects the article on the board. She makes her thinking public (also known as Think Aloud Protocol) as she reads through sentence by sentence. “When I see this, I notice that…” “I see the author did ____ by _____.” We see the figurative language, the use of pathos. So what we’re doing here is a close reading. This is the power of the mentor text. To allow students the opportunity and space to notice. She tells us to go through the rest of it to pick out elements. Pick a lens and go at it. What are you interested in as a writer? Communicating a particular tone? Using evidence to prove a point? Narrow your gaze to that and see how the article does it.

Amy tells us to make sure you start your genre study out with an unassuming, unclever piece. This makes it easier to figure out what the defining characteristics of a genre are. Amy takes weeks to go through mentor texts in a genre study. She puts them up on Edmodo.

Once we’ve gone through the mentor text stuff, we try to find our own passion. Passion isn’t necessarily a love thing, just anything you feel a massive emotional charge about. We think of a couple of examples of things we’re passionate about.

Then, we move through a few well-constructed organizers taking us from passion to editorial topic to writing controversial questions to thinking about your evidence. She then has us cut it up. Rearrange words, paragraphs, sequence, etc. It’s a cool way of writing and prewriting and revising. You don’t have to start with X. No two editorials are the same using this method (which works for pretty much any other genre, btw).

Amy has many shout-outs. Penny Kittle, Jim Burke, the Serial podcast, Katie Wood Ray, and more.

What a fantastic presentation! Time for a quick break before we’re back into it.

If you tell your students what to say and how to say it, you may never hear them, only the pale echos of what they imagine you want them to be. -Donald Murray