Category: NVWP

Writing Alongside My Students

Jorge jiggled his knee as I read over his story, his anxiety palpable. “It’s just… I mean… I know there’s a lot,” he said as he raked his hand through his spiky hair for the third time in as many minutes. He was right. By the end of the first page I counted at least eight characters and four drastically different settings. For feedback, I told him two things. First, that as a reader I was having a hard time figuring out who to focus on. Then I told him to listen as I read his story back to him. Which part of his story excited him the most? He zeroed in on a character (Tommy and his magical Book of the Dead) and left the conference with a more manageable scope to his story.

The rest of last week’s story conferences proceeded along similar routes. Sometimes the feedback was easy: insert a piece of dialogue that foreshadows the character’s conflict. Other times, it wasn’t. Helping writers nurture their strengths is a complex constellation of skills that I will probably never master. Anytime I felt stymied, I reached for Angela Stockman‘s fantastic Talking with Writers 2018. Talking with Writers devotes a section to responding to common problems in student writing. The strategy I used with Jorge came from Stockman’s work.

The ease with which I was able to apply this type of “See X? Try Y!” logic to student writing took me by surprise. As a committed member of the Northern Virginia Writing Project, I’ve always advocated for the power of writing alongside my students. And, following the work of Paul Thomas, I’ve also labored to try and become a scholar of writing. I’ve pursued composition pedagogy and history, written blog posts, and lead in-service trainings about the importance of knowing your theory.

However it wasn’t my understanding of composition or my status as a writer that helped me help my students. At least, I don’t think it was. Framed by schooling’s twin ideologies of efficiency and outcomes, every conference was compact and results oriented. Here’s what I see; here’s where you need to go; here’s a strategy to get you there. Does being a teacher of writing who writes provide any sort of advantage in this situation? Is this even the question to ask?

Normally, if my students are writing, so am I. It’s become an important part of my practice. It reminds me that writing exists outside of high-stakes accountability and the testing trap. It shows me that writing cannot be contained by formulaic essay constructions or meaningless assignments. But this method of instruction takes time, a teacher’s most valued currency. Every minute I spend writing alongside students is a minute I don’t have to confer with them.

During this last realistic fiction unit I chose not to write with them. I went with the more common alternative: work on something at home and bring it in as an example. I had more time to meet with my students, but I also felt disconnected, like a detached head floating above my students.

The debate over how best to spend class time isn’t new. In 1990, Karen Jost set off a firestorm within the secondary Language Arts community by arguing that the cost of writing with students outweigh the benefits. Students are best served by a teacher who meets with them and provides feedback, not by a teacher who labors over their own manuscripts. Jost lists the dizzying array of duties administrators and families expect of secondary teachers. With this list in mind, it is hard to imagine how teachers can confer with students, give daily instruction, provide written feedback, attend school functions, etc. and still find the time to sit down and write.

Ideally, we would do both. We would workshop their pieces with our students, in the process modelling authentic purposes, purposeful revision, and the writing life. As we did this, we would confer with students and do our best to guide them through the infinite complexity of composition. But there is not enough time to do both.

There is no answer. Or if there is, I don’t know it. But I do know that what we do shows what we value. The pedagogies we enact are inextricably linked to who we are as teachers, writers, and professionals. We make sure to share our reading lives with students. We give book talks, do read alouds, and converse with our kids about the books that matter to us. Can we say the same about our lives as writers?

———————————————-

-Image credit: CC0 Photo by freestocks.org on Unsplash

Beyond Socratic Seminars and Essential Questions: The Importance of Student Generated Questions – NVWP Summer ISI – Day 14

Welcome to the Northern Virginia Writing Project’s 2016 Invitational Summer Institute! I’ll be blogging the demonstration lessons and the various activities occurring during our four-week duration. Find out more about the NVWP and the National Writing Project.

Today’s second presentation comes from Steph Lima. It explains how to use student-centered questions in the classroom.

Quickwrite: Write about your successes and challenges with either small and / or large group discussions.

Oh, boy. Discussion is something that I really need to work on. I’m acceptable at it, but nowhere near great. Right now I can only think of my deficits in this area. I need to work on finding the right balance of creating guiding questions and having a direction in mind vs. allowing a discussion to grow organic legs that allow it to move wherever. I know that it helps to write out a few sequenced questions before hand, to frame questions in affective ways, to begin with real-life scenarios, and to summarize/paraphrase student responses, and to help connect students to each other during the discussion. Perhaps some of my weakness comes from my fear of sustaining a whole class discussion for any length of time. I’m always so afraid children will get squirrely and bored and that the introverts will disappear.

We share out. Someone talks about how their own school experiences played a role in this. This gets me thinking. It’s hard for me to remember a time when I felt confident participating in a large scale conversation. This also relates to a larger feeling of alienation that I experience whenever talking about academic/intellectual things.

Stephanie tells us about the origin of her presentation. She was unsatisfied with the quality of student discourse, and she felt she was enabling it. Heads are nodding. She decided to revamp how she approached class discussion. She divided questions into three types:

She spent time with students going over questions, writing them, and categorizing questions that students brought in. This reminds me of the importance, again, of modeling and teaching the academic moves we expect children to do. Asking questions and conversing is actually a complex skill, one that requires multiple layers of cognition.

After students brought in their self-generated questions, they took turns passing them around, reading each other’s questions, and annotating. Then Steph had the students pick a few questions that weren’t theirs to answer in writing. Students then picked one of their answers to discuss with the small group. Then, after that, she opened it up to the whole class. By talking it out in small groups first, every student went into the whole-group with a variety of talking points. The power of constructivism!

Now it’s our turn. Steph passes out copies of “The School Children” by Louis Gluck. She says it offers a rich variety of analyses.

We read twice and then annotate for whatever we notice. Next we write as many questions as we can, keeping the previous levels in mind. After that we write our best two on sticky notes and put them in a pool on our group’s table. We pick two (that aren’t ours!) and then write answers to them. No one is speaking yet. After writing, then we begin sharing out our questions and answers with our group members. Holy smokes this poem is amazing!

This reminds me of a) the value of writing before discussing and b) how this sort of ‘write questions – put them in the center for everyone’ technique can be way more useful than ‘everyone look at each other and brainstorm out loud.’ This way there’s less pressure and I can come up with ideas at my own pace and even pick out from among my ideas the best ones to share out. Each group discusses. Zone of Proximal Development in full effect!

We share out. Many of us cry out to hear what the poem is “about.” Steph wisely stays mum on the subject. We often tell children “it’s not about the answer.” We must resist this temptation ourselves. Steph ends by telling us she has the kids write about and reflect on why they chose the questions they did, and etc. This approach was way more generative than her previous discussion techniques.

I cannot WAIT to do this next school year.

Harnessing the Power of Purpose and Audience: Authentic Writing in the Classroom – NVWP Summer ISI – Day 14

Welcome to the Northern Virginia Writing Project’s 2016 Invitational Summer Institute! I’ll be blogging the demonstration lessons and the various activities occurring during our four-week duration. Find out more about the NVWP and the National Writing Project.

Our final day of presentations begins with Sara Watkins talking to us about how she uses authentic writing in her high school classroom.

Quickwrite: Think about a writing assignment you’ve given that your students enjoyed. Describe the lesson: what was it? What was its purpose? Who was the audience for the students?

Towards the end of the year I ran the students through a Flash Fiction mini-unit. We read examples, took them apart to see what made them tick, and tried to figure out what the genre was all about. Students then created their own examples of Flash Fiction. I had them concentrate on conflict types, economy of language, and otherwise following the genre rules we discussed. I wanted the students to gain practice with honing in on various conflict types, working through plot elements, and figuring out how to say a lot with a few amount of words. The audience, unfortunately, was just the class. By the end of the year students knew that pretty much anything they wrote would be put up on the walls to be read and discussed with classmates.

BTW, authentic writing is pretty much any genre of writing that is “found in the real world” and written for an audience outside of the school. Authentic writing creates links to the community. Writing for an authentic audience helps children believe in the power of their own voice and their own story. Here are some examples of genres of writing used by non-teachers:

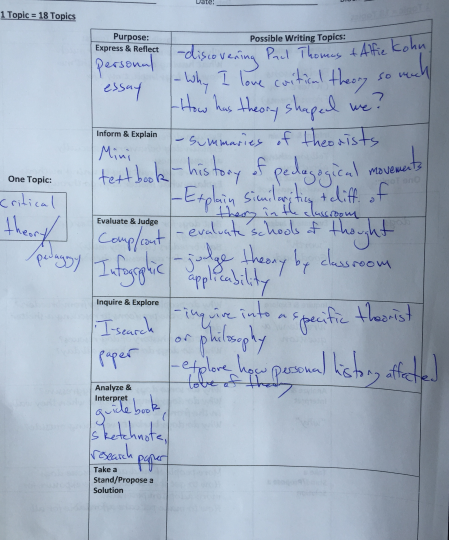

Sara passes out a Kelly Gallagher sheet on approaching one topic in 18 different ways. The left hand column represents six prominent purposes available for a topic. The right hand column offers some guidance on how to get started with each purpose.

Sara shows us a model of her own writing. She splits her favorite topic (dogs!) into the six purposes. Each purpose contains at least three topics about dogs. Yet another successful example of the basic guided release model (teacher walks the class through an already completed/in process example to show basically show students what to do. Then students are encouraged to do their own). Now it’s our turn to do the same! Here’s my example. I didn’t finish it in time. Sorry about the poor lighting.

We share out. It’s amazing what a wealth of information can come from just a single topic! Even if some of my/out ideas don’t fit squarely into each category, that doesn’t matter. What matters is generating tons of student-centered ideas from a single student-centered topic. The classroom is crackling with ideas and laughter.

I can’t wait to use this in my class this year. She ends up with a list of resources.

Picturing Writing: Empowering ELLs with Writing through Pictures – NVWP Summer ISI – Day 13

Welcome to the Northern Virginia Writing Project’s 2016 Invitational Summer Institute! I’ll be blogging the demonstration lessons and the various activities occurring during our four-week duration. Find out more about the NVWP and the National Writing Project.

Today’s second demonstration lesson comes from published author Natalina Bell. She’ll talk to us today about using pictures to enhance and empower ELL (English Language Learners) writing.

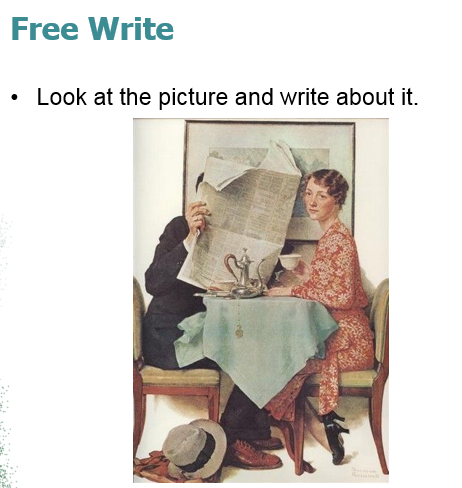

She gets us started with a freewrite.

Normally, Natalina would provide a word bank and sentence frames to help her ELL students get started. We go to work.

Ok. So what can I write about looking at this? I see presumably a man almost fully obscured by newspaper/news/things external to the moment. I also see a woman, presumably his wife, staring longingly/wistfully/somberly at an unknown point outside the frame. To be honest, I don’t really like Normal Rockwell images. I don’t actively dislike them, but they don’t do anything for me. I feel weird saying that, because I know a ton of teachers who find success using them in the classroom. I’ve used a few of them myself. But personally I don’t find anything to connect with. Ok, it’s a freewrite, so keep writing. I just zoned out for a second. Gotta practice what I preach! The stain on the table cloth is a nice touch, as is the depiction and positioning of her heels. She seems to be balanced somewhat precariously, pulling back from the husband’s angular and obtrusive presence. I can’t find much to connect with emotionally here, not much seems compelling. Nice details and etc. etc., but the subject doesn’t get me going. Instead my mind keeps pulling away into the psychic realm of worries, errands, and random thoughts. But I’m going to keep writing. Others in the room are bent forward, diligent in their completion of the warm-up. I wonder what they’re writing. When were these images popular, again? I’m sure there’s a ton of quality scholarship on Rockwell and his life/times/work. Maybe that would help me connect. Ok!

We share out. I’m in awe of the creativity in the room! A few of us created fictional stories from the image. Was I supposed to do that? I need to up my fiction game. Natalina tells us why she often starts with (and sticks with!) images:

ELL teachers face many challenges in the classroom. They must teach a room full of students with drastically different levels of English proficiency. Some ELL students come to the states without much experience in their ‘home’ language. ELL students also have different cultural experiences, making working from previous experiences and schema difficult. The difficult and essential and complex role of socialization. This is the dream of American compulsory education. No matter what or who or how we try to educate. This falls on teachers, as inequitable funding formulas and histories of racism make providing equitable education to all quite challenging.

Today’s lesson starts with one of 2nd grade classroom’s favorite books: Aliens Love Underpants. Great title! She reads it aloud to us. Who doesn’t love that? Today we get to create our own alien!

We only have five minutes. Here’s mine:

Next we present the alien in writing. We use the sentence frame that Natalina provides to her students to help scaffold. Sort of like Madlibs only minus the parts of speech. You can probably figure out the frame.

My name is Goopy, but most of my friends call me Lil Goops. I come from a solar system a billion light years away. I was born among the stars, as are all of my kin. I don’t have legs (what are those?); I float softly through the air, trailing a quiet melody behind me. I love eating space trash. That’s what brought me to this place! You all have so many delicious tidbits of space junk. And when I don’t have to go to school I like to tumble around in the atmosphere and feel the clouds tickle my fur. I hope we can be friends!

We share out. We love this. Natalina tells us normally she would videotape every presentation so she can share it with the student later. Students can use the image as a reference for what they will write. This is a neat point. The writing helps them generate the language. Natalina plays a few clips of her students presenting on their aliens. They’re wonderful. Many of the students project aspects of themselves onto their aliens. They map their strengths, weaknesses, and origin stories onto their creations. Natalina also uses images on notecards to help students practice sequencing stories and creating a logical flow from which to write. She has her students illustrate and describe nearly every aspect of the stories they read together.

Natalina ends up by sharing some resources with us. Sorry the links aren’t clickable!

Enjoy!

Using “This I Believe” Podcasts to Elevate Student Voice – NVWP Summer ISI – Day 13

Welcome to the Northern Virginia Writing Project’s 2016 Invitational Summer Institute! I’ll be blogging the demonstration lessons and the various activities occurring during our four-week duration. Find out more about the NVWP and the National Writing Project.

We kick off our final week of Summer Institute with Joanne Mann. She’s going to present to us on using “This I Believe” podcasts to elevate student voice. Can’t wait!

Joanne begins her demonstration by having us arrange ourselves along a value line as she reads us a series of affective statements such as “Violence is sometimes necessary,” “Everyone is basically good,” and “All students should be required to speak English.”

Quickwrite: Which one made you think the most? Did others’ positions influence where you stood?

“Love lasts forever” probably resonated with me the most. To begin with, I don’t believe in soul mates. For me love is something that’s built up over time through the accumulation of shared experiences and the continued rejection of outside threats. I also try to think about my family and spouse dying a few times a week. I started doing this after reading about it on a mindfulness website. As a way to remind myself of life’s impermanence and to truly live in the single moment. In one sense, love lasts forever because it, and the memory of it, can remain in someone’s mind. Time’s up!

Here are the objectives for today’s lesson:

We’re doing this for a few reasons. It helps students develop technology skills. It helps them to reflect on their voice and to understand that their voices matter.

We listen to a podcast on Muhammad Ali from Muhammad Ali. This is the first draft reading; we sit and take it in. After this Joanne passes out the transcript of the podcast. Ali discusses his confidence growing up and how Parkinson’s Disease has affected him. The story culminates in Ali holding the Olympic Torch at the 1996 summer games. As he felt his trembles take over he heard a thunderous ruckus storming down from the stadium. Terrific story.

Next we do our second draft reading, annotating the transcript as we listen again. We share out. I discuss how Ali’s story seems quintessentially American. The idea that will and determination can triumph over everything. Others mention that Ali must have experienced failure and disappointment, but he chooses to focus on the triumphant aspects.

Then we create categories to make observations on about the text and fill them in on the following sheet. She runs is through two examples first (the guided release model) before having us work with our partner:

We come up with categories like theme, details, and structure/organization. After sharing out Joanne has us turn out attention towards another podcast. We have a few to choose from. I choose “A Grown-Up Barbie” from Jane Hamill (all of these come from the This I Believe book). I read it and analyze it for structure, theme, and details. I also jot down anything I notice about the piece. Joanne’s methodology here fits in with the type of model-based analysis currently popular among secondary English teachers.

Now that we’ve listened to a podcast, read two transcripts, and discussed both it’s time for us to create one ourselves.

So, what do we believe? Why do we believe it? What happened to us that created that belief? How has it been reinforced? She passes out a planner (I love planners, btw! I know they’re frowned upon in some circles – and I get it – but my attention deficient brain finds them extremely useful in organizing my thinking). Here’s what I come up with.

After completing the planner we spend time crafting our own brief “This I Believe” essay. The ultimate goal is to then record them using free software (such as the Voice Memos app which comes installed on every iPhone). Let’s give it a shot!

“Honey. This is ridiculous,” my wife said, frowning down at my desk with her hands on her hips. I had to agree with her. My massive white desk, once cramped with books and papers, was now completely obscured by composition text books, histories of education, and expensive books on pedagogy.”

Crud! Out of time!

Joanne ends our lesson by playing a couple examples from her students. Outstanding!

A Masterclass in Writing Fiction pt. 2 – NVWP Summer ISI – Day 12

Welcome to the Northern Virginia Writing Project’s 2016 Invitational Summer Institute! I’ll be blogging the demonstration lessons and the various activities occurring during our four-week duration. Find out more about the NVWP and the National Writing Project.

See pt. 1 of this amazing session here. As I’m blogging this as it occurs, the post will have a certain disjointed quality to it.

Mark Farrington continues his presentation on writing fiction with a discussion on the intersections of reality and fiction. He reminds us that:

1. Fiction is not reality.

2. It’s not a mirror of reality.

3. It’s an illusion of reality.

You don’t try to duplicate reality. You suggest it and let readers react to it. What details are essential for the reader to know? You must convince the reader to believe in your story.

Tips for writing fiction based on real life:

1. Changing the name

2. Changing the gender

3. Changing a key personality quirk

4. Changing the events or the outcome of events

5. Looking for metaphorical or symbolic truth vs. literal truth

6. Realizing that the setting is often the easiest to both “steal” and “alter”/fictionalize

Gain distance from a real life story by asking yourself “What if?” and then following your line of thought. Mark says this also works if you’re at a point in your story when you feel it’s slowed down.

Mark also recommends the Mr. Potato Head approach. You can pull different personality and setting and plot aspects from whatever you want. It’s not who or what you based it on that matters, it’s how you manipulate it and how it ends up on the page.

Another tip Mark suggests is the “situation / catalyst” approach. First you come up with an interesting situation (one that has potential for conflict and tension). But without an initiating event nothing happens. Therefore you try to think up a catalyst that gets the plot going. The catalyst is an event or situation that makes the tension of the situation concrete and real.

Don’t try to force the ending. Writing fiction is like driving a car at night, he says. You can always see in front of you, and you get where you need to get, but you can’t always see the path. I’m reminded, not for the first time, of the disconnect between what Mark is saying and the way many of us (myself included) teach fiction writing. I’m not necessarily saying Mark’s word is gospel, but it’s important to think about the ramifications behind what we do and why we do it.

Prompt: Building a character. Mark asks us questions and we write down answers to each one. Quick rapid fire. The only rules are that the character you create must be human. Try not to base the character on a real person.

1. What gender is this character? M

2. What age? 23

3. What words or phrases describe this character’s appearance? Puny, emaciated, hunched

4. What about the way your character looks would they like to change? giant ears

5. Where does your character live? Arlington, VA

6. What kind of structure do they live in? A micro-home

7. Who else lives there? Three cats and a bird

8. What’s their favorite place within the structure they live in? The bathroom. Twee wall paper, retro shag carpeting, furry toilet seat cover, and, most importantly, a giant mirror.

9. What do they like to eat for breakfast? Poptarts with frosting on them

10. What work do they do? OR how do they spend their weekdays? Sweeping hair at an all-male salon

11. Speaking in the voice of your character, finish the sentence: ‘It makes me angry when…’ I get a haircut and my ears are always clipped,

12. What clothing do they wear when they want to feel comfortable? Skinny jeans, snug sweaters, beanie cap pulled down tight

13. How does your character usually spend Sunday morning? Making boutique teas for the old folks living in his apartment complex, delivering door to door

14. What vehicle do they drive / ride in most often? A battered brown bike with a deflated, punctured black horn attached to the right handlebar

15. Which parent was more important? Dad, he made sure his kid grew up on a steady diet of Led Zeppelin and other hard rock staples\

16. Finish the sentence in the character’s voice: ‘I am afraid that/of…’ people will see the way I dress and reduce me to a hipster stereotype

17. What is the educational background? HS grad, community college associate’s degree in progress

18. When confronted with a decision, is your character decisive or ruminative? Quick-witted and decisive

19. Does your character believe that the world is orderly and fair or chaotic and purposeless? Orderly and fair

20. Finish the sentence in your character’s voice: ‘I don’t know why I remember the time…’ my dad brought me home a furby, a special Kiss edition complete with Gene Simmons tongueWrite five of this character’s stepping stones. Two of them have to be what the character would describe as ‘difficult.’

- I was born on September 12th, 1995

- Dad played my first Zep record

- Got my first crush on my 3rd grade babysitter

- Parents divorced

- Dropped out of college

- Moved to new apartment and bonded with the building’s septuagenarian population

That was frustrating! I had to keep going even though I wasn’t satisfied with most of my answers. Now we begin to write a story in the first-person voice of this character. They have to talk about one of the difficult stepping stones or begin with “I don’t know why I remember the time…” Okay, let’s do this.

I don’t know why I remember it. The Furby I mean. Pops didn’t normally bring me home gifts. When I think about it I’m pretty sure that was the only thing he ever got me outside of a holiday.

He called me into the living room where he was seated with Ma. Her eyes looked real red, I could tell she had been crying. We need to have a talk, he said. But I can’t remember anything he said. It was like one of those Charlie Brown wom-wom-wom voice overs, you know? I sat down on the ruddy carpet, almost prostrating myself before the thing. It sat on the living room table, a heavy oak thing my dad picked up from some country store.

I was afraid to touch it. Maybe I was afraid that if I touched it I would break the spell and whatever my parents were saying would reach me. So I just sat there, transfixed by the thing’s plastic eyes and ridiculous eyelashes. I don’t know how long I stayed like that.

You don’t have to do these types of exercises, Mark says, but they can be helpful for generating content or fleshing it out. Have students volunteer questions for the class to use. He also brings up interviewing your character. Asking them, “why did you do X?”

Here are some more story prompts for getting started with fiction:

He ends by reminding us that most people don’t build stories like a bookcase. We don’t start with exposition, rising action, etc. The form grows out of the piece, not the other way around. And besides, not all stories follow story grammar.

Hope you’re able to glean some useful info from this wonderful presentation!

A Masterclass in Writing Fiction pt. 1 – NVWP Summer ISI – Day 12

Welcome to the Northern Virginia Writing Project’s 2016 Invitational Summer Institute! I’ll be blogging the demonstration lessons and the various activities occurring during our four-week duration. Find out more about the NVWP and the National Writing Project.

Today we are honored to have a presentation from Mark Farrington, an assistant director and professor at Johns Hopkins University. He’s going to speak with us about ways to get started writing fiction. We begin by exploring two quotes:

A story is not made like a bookcase, he says. You don’t assemble the materials, draw up a plan, and then follow the plan to put it all together. We have stories inside ourselves already. That doesn’t mean you can’t teach fiction writing; it’s our duty to help students master the skills and techniques to bring their stories out and tell them in the most effective way. I’m reminded of George Hillocks who wrote that we’re always planning and always prewriting and always engaged in some form of inquiry.

A successful piece of fiction has to do two things. It must demonstrate craft, skill, thought, judgment, and control. It also must produce surprise and mystery and tension and spontaneity. Mark divides the writing process into two sides: discovery and communication. We discover the affective and natural content within us and then work rhetorically to shape it into an effective mode of communication. Children, Mark says, have the discovery side down. Say “birds!” to them and they’re off writing. Adults, on the other hand, are wrapped up in the control side. If you say “birds!” to them you’ll hear “What kind? How many? What’s the point?”

Writing Prompt: He guides us through a visualization exercise involving creating a room and a person in our mind. Someone in our mind that might remind of us our Uncle Fred is not our Uncle Fred. It is ours. We own it. He tells us that fiction writers are thieves. We write.

I see an angular, modernist room. The type you would find in a Frank Lloyd Wright home. It has white walls, luxurious white carpet, and built-in book cases stuffed with books old and new on every possible topic. The book shelves surround the room on all sides. Large fluffy couches line the perimeter of the room. In the back is a giant desk littered with papers, dog-eared books, and various colorful trinkets. Inside the room with me is a man who resembles Michel Foucault. Tall, bald, well-dressed (but not pretentious), and with round spectacles. He is friendly and erudite, eager to talk with me about what I’m thinking and reading and writing. He never tires of conversing with me. He is always positive and interested in my intellectual pursuits.

We share out about how it felt to do this. Personally it was quite enjoyable. I tried to let the details come into focus naturally without forcing it.

If you don’t want to use this visualization with students, have them study photographs and begin to tell the story of that person. Start with the discovery and then shape and communicate it. Take what you have and make it your own.

Mark’s Rules for Fiction:

1. Fiction is character under pressure. It becomes interesting when characters are pushed outside of their comfort zone. You find out how someone really is by how they act and respond to pressing situations. There are two kinds of pressure: internal and external. Characters face external pressures tend to be not necessarily super dramatic. Internal pressure often comes from some sort of desire, he says. The best fiction has both.

I’m struck by the fact that we haven’t spoken about plot diagramming, human vs. human conflict types, exposition, etc.

2. The lifeblood of fiction is tension. What causes worry creates tension. For people who care about you see you worrying, they feel tension. The same happens in fiction. When we care about a character, we are invested in their tension. This means figuring out what the character is worried about, not figuring out how to put as many crazy things into a situation as possible. We have narrative tension (what’s gonna happen?) and textual tension (when the reader is questioning the text – what’s true? what’s metaphorical?),

Mark says to put tension on every page. One big tension is not enough. If the only question is whether or not Romeo and Juliet will get together then we might as well skip to Act V. We need big worries and little worries. Little tension that get in the way of dealing with big tension.

3. Almost all stories eventually move into a notion of “one day.”

4. Stories move toward a moment of illumination. Mark says thinking that a story must involve character transformation isn’t quite right. He says that instead either the character, the reader, or both must have a moment of new understanding. Seeing something different.

5. If 10% of a story is the intro, and 20% is the ending, what happens in the middle 70%? This is when to make the story believable, to show relationships and present character, to increase tension, and to build in themes (if necessary). Make the story feel believable for what it is. Moby Dick, he says, is about a guy with a crazy boss. If you’re going to make it work at a story level then you have to sell the guy with the crazy boss. You have to build it in consciously.

6.”What happens” in a story is less important than what it means to the characters it happens to. This is one of the most important things to realize, Mark says. I think immediately of all the student writing that deals with crazy plot events but with anemic character relationships. What is it like to be that person in that situation?

7. Writing fiction requires the writer to move back and forth between the conscious, critical mind and the subconscious, intuitive mind. Different genres require different percentages of time spent in each phase.

Next up we check out some first lines.

What observations can we make about these? What commonalities do we see? They imply future action. They leave you with a sense of space or character, but they don’t tell the whole thing. You’re intrigued, but not confused. Mark says the sentences tell us forward (what’s going to happen next?) and backwards (how did we get here?) at the same time. They raise questions. They also have a strong sense of voice, often with a key word or phrase embedded in the sentence that makes you want more.

Feel the difference between “There are cavemen in the hedges again” and “There are cavemen in the hedges.” Or “In walks three girls in nothing but bathing suits” vs. “In walks these three girls in bathing suits.”

Prompt: Write a first sentence to a story. You can only write the first sentence.

Okay. Here we go.

-I saw him coming through the front door. Only this time he didn’t see me.

-Coffee trickled across the pavement towards the body.

-This time, their secrets wouldn’t be enough.”

-The combination of tears and gasoline proved to be too much.

We share out. These are amazing! Mark suggests we put our first sentences in a Google Doc and pick one (that’s not ours) to continue. Amazing!

Continued in Pt. 2

Using Writing Conferences to Implement the Writing Process– NVWP Summer ISI – Day 11

Welcome to the Northern Virginia Writing Project’s 2016 Invitational Summer Institute! I’ll be blogging the demonstration lessons and the various activities occurring during our four-week duration. Find out more about the NVWP and the National Writing Project.

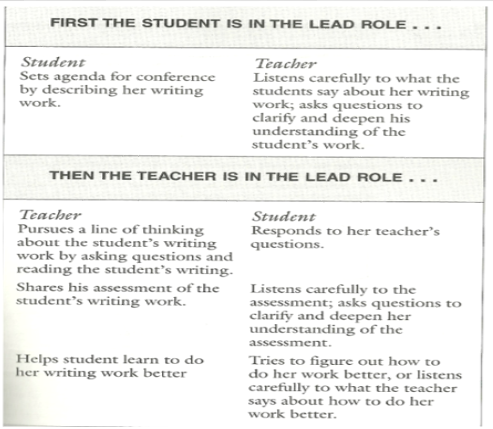

Our second demonstration lesson of the day comes from Matt Hendricks. He’s going to talk to us about the art of conferring with student writers. He begins by reminding us that conferring is incredibly complex, and that he isn’t coming to us with all the answers.

Quickwrite: Describe your first memorable experience a face to face writing conference.

Hmm. I can’t seem to think of anything off the top of my head. What does that mean? I do have a bizarrely deficient memory. The frustrating thing is that I’m sure I’ve had them; I just don’t remember them. For the sake of this quickwrite I’m tempted to make one up, but that doesn’t seem right. Everyone else around the room is fiercely scribbling, so I’m glad others are able to conjure something up! I was fortunate enough to live in an area with a lot of resources, so I’m positive my teachers spoke with me about my writing. I was never really a good student until college. The only piece of teacher feedback I can remember is when my senior year English teacher handed me back a paper and simply said “Think less.”

We share. Someone says their first conference was during college with Lad Tobin. I love Lad Tobin’s writing! Amazing. She remembers how he spoke of nothing but the content, choosing topics and themes instead of punctuation. Another person talks about the bonds created through her college conferring. As the room shares out I notice that most people mention college as the time of their first conference. These are not the answers I was expecting. It’s clear that there is a lot of energy in the room around conferring, around the relationships and the power dynamics and the trust involved in them. What an intriguing start!

Conferences are powerful.

Matt talks to us about the institutional pressures that work against conferring. How instituting a systematic program of conferring with students is likely to come against a lot of push-back. Conferences are a great way to provide students with a safe space to grow and exercise power.

What do we mean by conferences?

This slide has a lot of valuable details on it. While there are different ways to do confer, the most important aspect is just being present for the student and the student’s writing. He reminds us that students are often way more nervous about conferring than we are.

Carl Anderson is often considered a modern expert of the conference. He recommends conferring at every stage of the writing process.

1. Rehearsal: What’s the topic? This is a great way to make sure that students don’t feel sucker punched at the end of a writing assignment. Conferring in the beginning of the process can help the student select a topic that’s going to work.

2. Drafting: Developing the idea, checking out different genres and structures

3. Revision: Rethinking how ideas are being developed and presented, helping the student figure out what’s rhetorically important

4. Editing: Here’s the place, and pretty much the only place, to get at any glaring mechanical errors.

You teach the student, not the writing. The listening space is a learning space, O.F.L. says.

So, how do we do these? What do we say? What do they say? How do we track the conferences? We have so many questions! Carl Anderson provides a simple template to get us started:

1. Listen to the writer! Vicki Spandel says “Writers learn to be listeners first by having someone to listen to them.”

2. Invite them in with a question: How’s it going? What are you doing today as a writer? What do you need help with today?

3. Question: Avoid questions that only deal with content (teaching the paper) and instead focus on questions about the creation of the piece. For instance, why have you chosen this topic? Could you explain what you mean by…? What do you think you want to communicate with this piece?

4. Give specific, useful feedback: Describe what you see and then describe ways and means for students to improve the piece.

5. Teach a strategy or concept: Give an explanation, connect to a writing mentor, remind student of past lessons

6. Leave the student to write.

We watch Penny Kittle conduct three writing conferences with students. If you confer with students I recommend watching this clip. Penny annotates what she’s doing in conference along the bottom of the clip.

We close out our afternoon ready to try out our new conferring techniques in our writing groups. Fantastic!

Stretch A Little, Stretch A Lot: Using Hyperbole to Enhance Memoir Writing – NVWP Summer ISI – Day 11

Welcome to the Northern Virginia Writing Project’s 2016 Invitational Summer Institute! I’ll be blogging the demonstration lessons and the various activities occurring during our four-week duration. Find out more about the NVWP and the National Writing Project.

Today’s first demonstration lesson comes from Katlyn Bennett, an amazing colleague. She’s going to show us how to study a mentor text, Roald Dahl’s Boy: Tales of Childhood, in order to use hyperbole to enhance details in a personal memoir.

The context of this lesson is an author study unit. Students pick an author they’re interested in and then read a variety of works by that author. This helps students tease out a particular author’s voice (syntax choices, literal/figurative language usage, tone and mood, etc.). Katlyn uses Roald Dahl as the mentor author for this project because his collected works run the genre gamut. She got the idea from Roald Dahl’s website. Today’s demonstration lesson comes from a unit with the following objectives and essential questions.

Katlyn links this unit and lesson to Kelly Gallagher’s two central premises from Write Like This:

1. Introduce young writers to real-world discourses (express and reflect)

2. Provide students with extensive teacher and real-world models.

She also discusses reading as a process. First draft reading is for meaning and second draft reading is for techniques/craft/nuance/etc. Another way to think about this is as reading as a reader (immersion) vs. reading as a writer (analysis of rhetoric). This assignment and this unit focus heavily on reading and writing on process.

Quickwrite: Look back in your memory. Think about a time you got in trouble, were injured, were angry, were happy, etc. Now write down what happened. This is a no-nonsense summary of events.

When I was in 7th grade I wrote stories back and forth with a classmate and friend. These stories tended to be pretty gross depictions of comical sexual acts and explosions of bodily fluids. This is pretty standard stuff for hormone-addled middle school boys. I know this because I teach 7th graders. Oh wait, this is supposed to be no-nonsense.

I wrote a gross note to a friend. My English teacher confiscated it and I went to the principal’s office. I had to read it to my parents, apologize, and write an apology note.

Katlyn sets our purpose for reading (an excellent technique). What details stick out to us?

The section she reads is amazing. Dahl presents a truly grotesque depiction of a mean-spirited candy store owner. He knows how to zoom in on a key detail and then twist it into a disgustingly wonderful description. Dahl is also adept at immersing the reader in the memory and then sliding out of it to address the reader in a more authorial fashion. We discuss what we notice. Voice, point of view, hyperbole, characterization, and perspective are all mentioned. This is our first draft reading.

After she finishes we read the section again ourselves. At what point do we question the truth of Dahl’s writing? What images stand out? Is it okay if he’s not telling the 100% truth in his memoir? Katlyn comments to us that middle schoolers have a much harder time believing the veracity of every word or phrase, whereas adults don’t. Our conversation about truthfulness in memoir becomes wonderfully complex. Personally I believe that exaggeration and detail-massaging are not only acceptable techniques in a memoir but are essential to crafting an interesting narrative. It’s possible to tell the truth of the moment without being 100% factual, I think.

Now we return to our original quickwrite and look for details.

I wrote a gross note to a friend. It was funny! My English teacher confiscated it and I went to the principal’s office. He grabbed it from a kid. I had to read it to my parents, apologize, and write an apology note to the teacher. I got in trouble. It was embarrassing.

Katlyn puts up the following organizer to help us pick out details to stretch, and then stretch a lot. We’re looking for specific details to exaggerate. This is a great way to help children begin seeing writing as a series of rhetorical decisions. You can see the way she exaggerates and then hyperbolizes the facts.

Here’s mine!

-The note was gross ->

-The note was the stuff of schoolyard whispers. ->

-The crumpled paper oozed/was soaked the blunt, comical perversion of early adolescence.-My friend sat on the other side of the room. ->

-I could barely see Jackson’s flat top across the tiled expanse of the class. The note had to travel quite a distance to reach him. ->

-As Jackson and I sat on opposite sides of the room (a familiar teacher tactic for dealing with disruptions), our notes had to travel the precarious distance of the entire length of the room.-The teacher was watching us. ->

-His eagle eyes scanned the crowd for morsels. ->

-The teacher’s eyes swept over the class like searchlights hunting down an escape prisoner.

I realize that I exist in the hyperbole zone. This is my truth, the way my brain perceives and processes things. This makes sense with my earlier position on being liberal with the ‘truth.’ Oh, this is just so much fun. It really makes you focus on the purpose of every word. What choices would a journalist make? What about a comic? How do expectations about audience play into word choice? It’s probably best to finely tune the writing so it’s not either 100% over the top or 100% dry. Katlyn ends her presentation with a couple samples of student work.

Outstanding!

Writing in ESOL: A Journey – NVWP Summer ISI – Day 9

Welcome to the Northern Virginia Writing Project’s 2016 Invitational Summer Institute! I’ll be blogging the demonstration lessons and the various activities occurring during our four-week duration. Find out more about the NVWP and the National Writing Project.

Our second demonstration comes from Elissa Robinson. She’s going to talk to us about her first year teaching ESOL in the United States. Elissa taught for three years in Japan before coming back to the states last year.

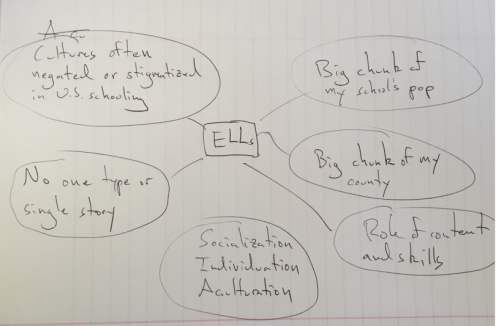

Quickwrite: What do you think of when you hear ESOL (ELL, ESL)? Put ESOL in the middle of your paper and make a web to show your thoughts.

Elissa talks us through her personal background and how she got into teaching. She has a fascinating story that gets to the U.S. by way of teaching English as a Foreign Language (EFOL) in Japan.

Teaching English Language Learners (ELLs) presents a wide array of challenges. Many of us take for granted the fact that the children we teach (especially by middle school where I teach) are already fairly socialized into the social order. Many ELLs come to us from different cultures with drastically different norms. They have to take many mandated computer exams (confusing for students who don’t know what a computer is).

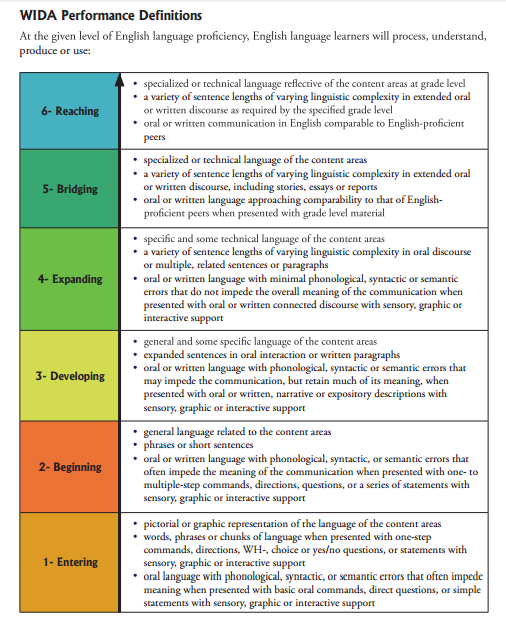

ELL teachers must go by the WIDA performance descriptors. Students aren’t allowed to exit out of ELL services until they receive a combined score of 6 on the four domains of language: reading, writing, speaking, and listening. Elissa works with Level 1 and Level 2 students. Here are the descriptors:

Elissa speaks to us in Japanese for a couple minutes. Although she tosses in a few English words, we have absolutely no idea what she’s talking about. And then she asks us to reflect on how we felt. The stipulation is that we can only use 1-2 syllable words.

This activity is probably designed to give us a taste of what it’s like to sit in a classroom where someone speaks at you in a language you can’t understand. Oh wait, this is supposed to be 1-2 syllable words.

I felt bored. Fun at first, but that fast turned into being confused. I had no clue what to say or what she wanted me to do. It was easy to tune out. It made me think about my own use of language in class, both I say and how I say it.

Elissa says she saw many familiar faces from her ELL classes in the room. Some of us were on the edge of our seat, eagerly trying to tease out what she was saying. Others sat dumbfounded and slackjawed (I fall into the category). And some just glazed over. We share out how we felt and the consensus seems to be confused, lost, and rendered mute by the maze of language.

The purpose, she says, was to put us in the mindset of her students. Teaching writing to a population with this unique set of capabilities presents a number of challenges. The room erupts. Everyone here has powerful experiences working with ELL populations. Our stories are never about the children; they’re all about the policies and practices used by schools and districts. Immersion, mainstreaming, push in/push out, accountability testing, etc.

Elissa says she’s going to share with us a few different activities she uses in her class. The first is called “What’s Next Writing.” Elissa passes a bag around. The bag contains lots of small tiles with pictures. We all take a single tile and then proceed to create a chain of associations.

I have a picture of a waterfall. I see a waterfall. Waterfalls are out in nature. I’m not that big a fan of nature. My wife loves nature. She is short and squat like me. I’m 5’7, which is an inch below average height. Students love comparing heights. The Heights was a terrible TV show in the 90s. I was an adolescent during the 90s. That makes me a cusper between Gen X and Millennials. I always forget that millennium has two Ms. Remember that show Millennium with Bishop from the movie Aliens? I blame watching Aliens 500 times as a child on my intense fear of spiders.

Writing this was an interesting experience. It felt like I was taking the constraints off of my ADHD. I had to consciously make sure I didn’t go in-depth with any of the sentences. I wonder about this type of writing. I seem to be forcing/creating connections between various schemata. How does this type of writing function with the brain-based cliche of ‘what fires together wires together’?

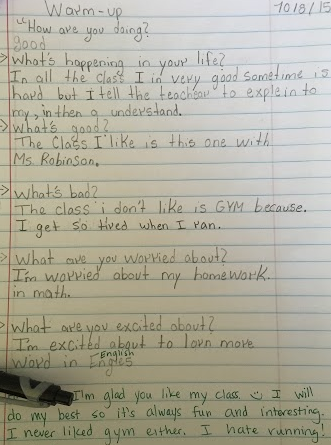

Next up we have dialogue journals. Every Friday each student under Elissa’s tutelage would write something to her in a dialogue journal. They become places for ELL students to become low-stakes writing. She provides specific encouragement and feedback for each student, giving them increasingly complex tasks. The journals display growth from the beginning of the year to the end. These journals are amazing. Elissa also asks students to write a letter to next year’s Level 1 ELL students as a way to give them a “here’s the skinny on what you’re about to experience.” Awesome. These also, in a way, remind me of Family Dialogue Journals. Here’s a sample:

We love these, btw. The progression of writing from the beginning of the year to the end is just amazing. Students can have dialogue buddies and respond to one person back and forth throughout the quarter. They can go with parents, etc. Many options. Elissa tells us how the journals become a safe space for the students to reflect.

The last thing she has us do is create a Facebook profile for a character from history or literature. It also works for concepts. The applications are numerous. You have to add writings on the wall from others, monologues, relationship status, likes, friends, and etc. Although Elissa gives us a handout with the template on it, you can also do it online using the free website Fakebook. We’ve done this with Tweets as well.

We’re running out of time, so Elissa wraps up her presentation with This lesson reminds me that “best practices” aren’t always that. Phrases like “good teaching is good teaching” mask the fact that students are always in different developmental places. That said, there are some tips: speak slowly, use multiple checks for comprehension (asking ‘what are your questions?’ instead of ‘do you have any questions?’), and more. What a great presentation!