Category: The Writing Process

“Have you READ their writing?” Resisting the Obsession with Mechanical Correctness

Listening to teachers complain about student writing is exhausting. They can’t write; they don’t know where to use commas; they don’t capitalize every i; their spelling is atrocious. When this sort of narrative pops up in mainstream discourse, it’s often to complain about education’s failure to prepare kids for the workforce and to provide a platform for ‘back in my day, teachers made us diagram sentences/memorize parts of speech/etc.’ bloviating.

When these sentiments appear inside a school, they take on a slightly different tenor. Behind every complaint about a kid’s writing seems to be an underlying message about the failure of that child’s previous language arts teacher(s). It’s as if the teacher is throwing their hands up and proclaiming ‘Look at the mess I inherited! What am I supposed to do? How can I teach my content when these kids don’t even understand the basics!’

There’s a lot to unpack here. First, this nagging is counterproductive and can build resentment among teachers. Schools have more than enough finger-pointing as it is; engaging in ego-driven grandstanding serves no one.

To the teachers who regularly engage in this sort of carping, please stop. If you don’t like what your students are producing, then address it in the classroom. Regardless of content or grade, helping children learn to read, write, speak, and think is everyone’s responsibility. These complaints also elevate surface features (spelling, grammar, basic syntax) above all else.

The notion that mechanical perfection is the goal of writing instruction is deleterious to good teaching. It reinforces a deficit view of student writing by focusing on what a child did wrong. It trains us to approach student writing as something to be endured, some sort of gauntlet all language arts teachers must go through. It also encourages teachers and students to see writing as a series of levels to be mastered. Writing doesn’t care about scope and sequence documents or district-wide vertical alignment. It grows in fits and starts, evolving through recursive spirals of progress and regress.

Historically, evidence shows that teachers have been complaining about student writing since the first American universities. In The Rise and Fall of English, Robert Scholes examines primary documents such as university syllabi and commencement speeches to conclude that

English teachers have not found any method to ensure that graduates of their courses would use what were considered to be correct grammar and spelling. A number of conclusions can be drawn from this situation. One is that the good old days when students wrote “correctly” never existed. A second conclusion might well be that two hundred years of failure are sufficient to demonstrate that what Bronson called beggarly matters (spelling, grammar, capitalization, punctuation) are both impossible to teach and not really necessary for success in life. (p. 6)

This isn’t all to say that mechanical correctness doesn’t matter. The above notion that grammar and spelling are not “necessary for success in life” should be followed by “for certain people.” I’m reminded of an anecdote from Christopher Emdin’s For White Folks Who Teach in the Hood. Emdin recounts a conversation with a white teacher about the role of appearance. The teacher doesn’t understand why her students of color seem so focused on fashion and style. What do these things matter? After all, she says, she comes to school every morning in casual dress. Emdin replies that the ability to be treated professionally regardless of dress is a luxury many people of color can’t necessarily afford.

So of course grammar and spelling matter. Certain errors like nonstandard verb forms and incorrect subject/verb agreement can carry serious connotations of race and class. The legacy of mechanical correctness is steeped in racism, xenophobia, and class anxiety (for more on this, check out Mechanical Correctness and Ritual in the Late Nineteenth-Century Composition Classroom by Richard Boyd and The Evolution of Nineteenth-Century Grammar Teaching by William Woods). As teachers, we have the responsibility to help students understand the intersections of power and literacy. But this doesn’t mean chastising students for every mistake they make in their writing. Nor does it mean requiring every student draft to be mechanically perfect.

My go-to authority for how to treat errors in student writing is Constance Weaver. She urges us to see errors as a necessary component of growth. The following chart, taken from her Teaching Grammar in Context, sums up what a more compassionate and purposeful approach towards errors might look like.

Along with the solid tips outlined above, remember that students should focus on superficial edits using their own writing, on a topic they care about, during the final stages of the writing process.

If nothing else, stop complaining about student writing. It’s counter-productive to our mission and makes an already exhausting job that much more draining. If you’re not enjoying yourself, neither are they.

A Masterclass in Writing Fiction pt. 2 – NVWP Summer ISI – Day 12

Welcome to the Northern Virginia Writing Project’s 2016 Invitational Summer Institute! I’ll be blogging the demonstration lessons and the various activities occurring during our four-week duration. Find out more about the NVWP and the National Writing Project.

See pt. 1 of this amazing session here. As I’m blogging this as it occurs, the post will have a certain disjointed quality to it.

Mark Farrington continues his presentation on writing fiction with a discussion on the intersections of reality and fiction. He reminds us that:

1. Fiction is not reality.

2. It’s not a mirror of reality.

3. It’s an illusion of reality.

You don’t try to duplicate reality. You suggest it and let readers react to it. What details are essential for the reader to know? You must convince the reader to believe in your story.

Tips for writing fiction based on real life:

1. Changing the name

2. Changing the gender

3. Changing a key personality quirk

4. Changing the events or the outcome of events

5. Looking for metaphorical or symbolic truth vs. literal truth

6. Realizing that the setting is often the easiest to both “steal” and “alter”/fictionalize

Gain distance from a real life story by asking yourself “What if?” and then following your line of thought. Mark says this also works if you’re at a point in your story when you feel it’s slowed down.

Mark also recommends the Mr. Potato Head approach. You can pull different personality and setting and plot aspects from whatever you want. It’s not who or what you based it on that matters, it’s how you manipulate it and how it ends up on the page.

Another tip Mark suggests is the “situation / catalyst” approach. First you come up with an interesting situation (one that has potential for conflict and tension). But without an initiating event nothing happens. Therefore you try to think up a catalyst that gets the plot going. The catalyst is an event or situation that makes the tension of the situation concrete and real.

Don’t try to force the ending. Writing fiction is like driving a car at night, he says. You can always see in front of you, and you get where you need to get, but you can’t always see the path. I’m reminded, not for the first time, of the disconnect between what Mark is saying and the way many of us (myself included) teach fiction writing. I’m not necessarily saying Mark’s word is gospel, but it’s important to think about the ramifications behind what we do and why we do it.

Prompt: Building a character. Mark asks us questions and we write down answers to each one. Quick rapid fire. The only rules are that the character you create must be human. Try not to base the character on a real person.

1. What gender is this character? M

2. What age? 23

3. What words or phrases describe this character’s appearance? Puny, emaciated, hunched

4. What about the way your character looks would they like to change? giant ears

5. Where does your character live? Arlington, VA

6. What kind of structure do they live in? A micro-home

7. Who else lives there? Three cats and a bird

8. What’s their favorite place within the structure they live in? The bathroom. Twee wall paper, retro shag carpeting, furry toilet seat cover, and, most importantly, a giant mirror.

9. What do they like to eat for breakfast? Poptarts with frosting on them

10. What work do they do? OR how do they spend their weekdays? Sweeping hair at an all-male salon

11. Speaking in the voice of your character, finish the sentence: ‘It makes me angry when…’ I get a haircut and my ears are always clipped,

12. What clothing do they wear when they want to feel comfortable? Skinny jeans, snug sweaters, beanie cap pulled down tight

13. How does your character usually spend Sunday morning? Making boutique teas for the old folks living in his apartment complex, delivering door to door

14. What vehicle do they drive / ride in most often? A battered brown bike with a deflated, punctured black horn attached to the right handlebar

15. Which parent was more important? Dad, he made sure his kid grew up on a steady diet of Led Zeppelin and other hard rock staples\

16. Finish the sentence in the character’s voice: ‘I am afraid that/of…’ people will see the way I dress and reduce me to a hipster stereotype

17. What is the educational background? HS grad, community college associate’s degree in progress

18. When confronted with a decision, is your character decisive or ruminative? Quick-witted and decisive

19. Does your character believe that the world is orderly and fair or chaotic and purposeless? Orderly and fair

20. Finish the sentence in your character’s voice: ‘I don’t know why I remember the time…’ my dad brought me home a furby, a special Kiss edition complete with Gene Simmons tongueWrite five of this character’s stepping stones. Two of them have to be what the character would describe as ‘difficult.’

- I was born on September 12th, 1995

- Dad played my first Zep record

- Got my first crush on my 3rd grade babysitter

- Parents divorced

- Dropped out of college

- Moved to new apartment and bonded with the building’s septuagenarian population

That was frustrating! I had to keep going even though I wasn’t satisfied with most of my answers. Now we begin to write a story in the first-person voice of this character. They have to talk about one of the difficult stepping stones or begin with “I don’t know why I remember the time…” Okay, let’s do this.

I don’t know why I remember it. The Furby I mean. Pops didn’t normally bring me home gifts. When I think about it I’m pretty sure that was the only thing he ever got me outside of a holiday.

He called me into the living room where he was seated with Ma. Her eyes looked real red, I could tell she had been crying. We need to have a talk, he said. But I can’t remember anything he said. It was like one of those Charlie Brown wom-wom-wom voice overs, you know? I sat down on the ruddy carpet, almost prostrating myself before the thing. It sat on the living room table, a heavy oak thing my dad picked up from some country store.

I was afraid to touch it. Maybe I was afraid that if I touched it I would break the spell and whatever my parents were saying would reach me. So I just sat there, transfixed by the thing’s plastic eyes and ridiculous eyelashes. I don’t know how long I stayed like that.

You don’t have to do these types of exercises, Mark says, but they can be helpful for generating content or fleshing it out. Have students volunteer questions for the class to use. He also brings up interviewing your character. Asking them, “why did you do X?”

Here are some more story prompts for getting started with fiction:

He ends by reminding us that most people don’t build stories like a bookcase. We don’t start with exposition, rising action, etc. The form grows out of the piece, not the other way around. And besides, not all stories follow story grammar.

Hope you’re able to glean some useful info from this wonderful presentation!

A Masterclass in Writing Fiction pt. 1 – NVWP Summer ISI – Day 12

Welcome to the Northern Virginia Writing Project’s 2016 Invitational Summer Institute! I’ll be blogging the demonstration lessons and the various activities occurring during our four-week duration. Find out more about the NVWP and the National Writing Project.

Today we are honored to have a presentation from Mark Farrington, an assistant director and professor at Johns Hopkins University. He’s going to speak with us about ways to get started writing fiction. We begin by exploring two quotes:

A story is not made like a bookcase, he says. You don’t assemble the materials, draw up a plan, and then follow the plan to put it all together. We have stories inside ourselves already. That doesn’t mean you can’t teach fiction writing; it’s our duty to help students master the skills and techniques to bring their stories out and tell them in the most effective way. I’m reminded of George Hillocks who wrote that we’re always planning and always prewriting and always engaged in some form of inquiry.

A successful piece of fiction has to do two things. It must demonstrate craft, skill, thought, judgment, and control. It also must produce surprise and mystery and tension and spontaneity. Mark divides the writing process into two sides: discovery and communication. We discover the affective and natural content within us and then work rhetorically to shape it into an effective mode of communication. Children, Mark says, have the discovery side down. Say “birds!” to them and they’re off writing. Adults, on the other hand, are wrapped up in the control side. If you say “birds!” to them you’ll hear “What kind? How many? What’s the point?”

Writing Prompt: He guides us through a visualization exercise involving creating a room and a person in our mind. Someone in our mind that might remind of us our Uncle Fred is not our Uncle Fred. It is ours. We own it. He tells us that fiction writers are thieves. We write.

I see an angular, modernist room. The type you would find in a Frank Lloyd Wright home. It has white walls, luxurious white carpet, and built-in book cases stuffed with books old and new on every possible topic. The book shelves surround the room on all sides. Large fluffy couches line the perimeter of the room. In the back is a giant desk littered with papers, dog-eared books, and various colorful trinkets. Inside the room with me is a man who resembles Michel Foucault. Tall, bald, well-dressed (but not pretentious), and with round spectacles. He is friendly and erudite, eager to talk with me about what I’m thinking and reading and writing. He never tires of conversing with me. He is always positive and interested in my intellectual pursuits.

We share out about how it felt to do this. Personally it was quite enjoyable. I tried to let the details come into focus naturally without forcing it.

If you don’t want to use this visualization with students, have them study photographs and begin to tell the story of that person. Start with the discovery and then shape and communicate it. Take what you have and make it your own.

Mark’s Rules for Fiction:

1. Fiction is character under pressure. It becomes interesting when characters are pushed outside of their comfort zone. You find out how someone really is by how they act and respond to pressing situations. There are two kinds of pressure: internal and external. Characters face external pressures tend to be not necessarily super dramatic. Internal pressure often comes from some sort of desire, he says. The best fiction has both.

I’m struck by the fact that we haven’t spoken about plot diagramming, human vs. human conflict types, exposition, etc.

2. The lifeblood of fiction is tension. What causes worry creates tension. For people who care about you see you worrying, they feel tension. The same happens in fiction. When we care about a character, we are invested in their tension. This means figuring out what the character is worried about, not figuring out how to put as many crazy things into a situation as possible. We have narrative tension (what’s gonna happen?) and textual tension (when the reader is questioning the text – what’s true? what’s metaphorical?),

Mark says to put tension on every page. One big tension is not enough. If the only question is whether or not Romeo and Juliet will get together then we might as well skip to Act V. We need big worries and little worries. Little tension that get in the way of dealing with big tension.

3. Almost all stories eventually move into a notion of “one day.”

4. Stories move toward a moment of illumination. Mark says thinking that a story must involve character transformation isn’t quite right. He says that instead either the character, the reader, or both must have a moment of new understanding. Seeing something different.

5. If 10% of a story is the intro, and 20% is the ending, what happens in the middle 70%? This is when to make the story believable, to show relationships and present character, to increase tension, and to build in themes (if necessary). Make the story feel believable for what it is. Moby Dick, he says, is about a guy with a crazy boss. If you’re going to make it work at a story level then you have to sell the guy with the crazy boss. You have to build it in consciously.

6.”What happens” in a story is less important than what it means to the characters it happens to. This is one of the most important things to realize, Mark says. I think immediately of all the student writing that deals with crazy plot events but with anemic character relationships. What is it like to be that person in that situation?

7. Writing fiction requires the writer to move back and forth between the conscious, critical mind and the subconscious, intuitive mind. Different genres require different percentages of time spent in each phase.

Next up we check out some first lines.

What observations can we make about these? What commonalities do we see? They imply future action. They leave you with a sense of space or character, but they don’t tell the whole thing. You’re intrigued, but not confused. Mark says the sentences tell us forward (what’s going to happen next?) and backwards (how did we get here?) at the same time. They raise questions. They also have a strong sense of voice, often with a key word or phrase embedded in the sentence that makes you want more.

Feel the difference between “There are cavemen in the hedges again” and “There are cavemen in the hedges.” Or “In walks three girls in nothing but bathing suits” vs. “In walks these three girls in bathing suits.”

Prompt: Write a first sentence to a story. You can only write the first sentence.

Okay. Here we go.

-I saw him coming through the front door. Only this time he didn’t see me.

-Coffee trickled across the pavement towards the body.

-This time, their secrets wouldn’t be enough.”

-The combination of tears and gasoline proved to be too much.

We share out. These are amazing! Mark suggests we put our first sentences in a Google Doc and pick one (that’s not ours) to continue. Amazing!

Continued in Pt. 2

Using Writing Conferences to Implement the Writing Process– NVWP Summer ISI – Day 11

Welcome to the Northern Virginia Writing Project’s 2016 Invitational Summer Institute! I’ll be blogging the demonstration lessons and the various activities occurring during our four-week duration. Find out more about the NVWP and the National Writing Project.

Our second demonstration lesson of the day comes from Matt Hendricks. He’s going to talk to us about the art of conferring with student writers. He begins by reminding us that conferring is incredibly complex, and that he isn’t coming to us with all the answers.

Quickwrite: Describe your first memorable experience a face to face writing conference.

Hmm. I can’t seem to think of anything off the top of my head. What does that mean? I do have a bizarrely deficient memory. The frustrating thing is that I’m sure I’ve had them; I just don’t remember them. For the sake of this quickwrite I’m tempted to make one up, but that doesn’t seem right. Everyone else around the room is fiercely scribbling, so I’m glad others are able to conjure something up! I was fortunate enough to live in an area with a lot of resources, so I’m positive my teachers spoke with me about my writing. I was never really a good student until college. The only piece of teacher feedback I can remember is when my senior year English teacher handed me back a paper and simply said “Think less.”

We share. Someone says their first conference was during college with Lad Tobin. I love Lad Tobin’s writing! Amazing. She remembers how he spoke of nothing but the content, choosing topics and themes instead of punctuation. Another person talks about the bonds created through her college conferring. As the room shares out I notice that most people mention college as the time of their first conference. These are not the answers I was expecting. It’s clear that there is a lot of energy in the room around conferring, around the relationships and the power dynamics and the trust involved in them. What an intriguing start!

Conferences are powerful.

Matt talks to us about the institutional pressures that work against conferring. How instituting a systematic program of conferring with students is likely to come against a lot of push-back. Conferences are a great way to provide students with a safe space to grow and exercise power.

What do we mean by conferences?

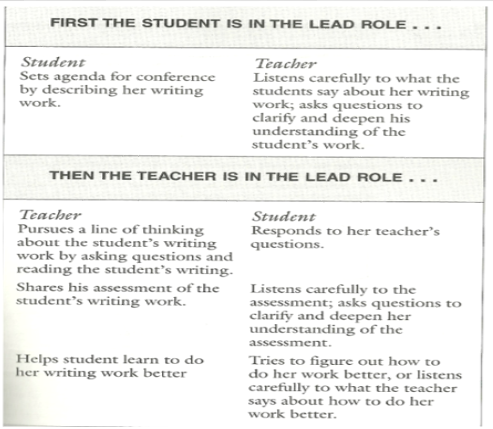

This slide has a lot of valuable details on it. While there are different ways to do confer, the most important aspect is just being present for the student and the student’s writing. He reminds us that students are often way more nervous about conferring than we are.

Carl Anderson is often considered a modern expert of the conference. He recommends conferring at every stage of the writing process.

1. Rehearsal: What’s the topic? This is a great way to make sure that students don’t feel sucker punched at the end of a writing assignment. Conferring in the beginning of the process can help the student select a topic that’s going to work.

2. Drafting: Developing the idea, checking out different genres and structures

3. Revision: Rethinking how ideas are being developed and presented, helping the student figure out what’s rhetorically important

4. Editing: Here’s the place, and pretty much the only place, to get at any glaring mechanical errors.

You teach the student, not the writing. The listening space is a learning space, O.F.L. says.

So, how do we do these? What do we say? What do they say? How do we track the conferences? We have so many questions! Carl Anderson provides a simple template to get us started:

1. Listen to the writer! Vicki Spandel says “Writers learn to be listeners first by having someone to listen to them.”

2. Invite them in with a question: How’s it going? What are you doing today as a writer? What do you need help with today?

3. Question: Avoid questions that only deal with content (teaching the paper) and instead focus on questions about the creation of the piece. For instance, why have you chosen this topic? Could you explain what you mean by…? What do you think you want to communicate with this piece?

4. Give specific, useful feedback: Describe what you see and then describe ways and means for students to improve the piece.

5. Teach a strategy or concept: Give an explanation, connect to a writing mentor, remind student of past lessons

6. Leave the student to write.

We watch Penny Kittle conduct three writing conferences with students. If you confer with students I recommend watching this clip. Penny annotates what she’s doing in conference along the bottom of the clip.

We close out our afternoon ready to try out our new conferring techniques in our writing groups. Fantastic!

Stretch A Little, Stretch A Lot: Using Hyperbole to Enhance Memoir Writing – NVWP Summer ISI – Day 11

Welcome to the Northern Virginia Writing Project’s 2016 Invitational Summer Institute! I’ll be blogging the demonstration lessons and the various activities occurring during our four-week duration. Find out more about the NVWP and the National Writing Project.

Today’s first demonstration lesson comes from Katlyn Bennett, an amazing colleague. She’s going to show us how to study a mentor text, Roald Dahl’s Boy: Tales of Childhood, in order to use hyperbole to enhance details in a personal memoir.

The context of this lesson is an author study unit. Students pick an author they’re interested in and then read a variety of works by that author. This helps students tease out a particular author’s voice (syntax choices, literal/figurative language usage, tone and mood, etc.). Katlyn uses Roald Dahl as the mentor author for this project because his collected works run the genre gamut. She got the idea from Roald Dahl’s website. Today’s demonstration lesson comes from a unit with the following objectives and essential questions.

Katlyn links this unit and lesson to Kelly Gallagher’s two central premises from Write Like This:

1. Introduce young writers to real-world discourses (express and reflect)

2. Provide students with extensive teacher and real-world models.

She also discusses reading as a process. First draft reading is for meaning and second draft reading is for techniques/craft/nuance/etc. Another way to think about this is as reading as a reader (immersion) vs. reading as a writer (analysis of rhetoric). This assignment and this unit focus heavily on reading and writing on process.

Quickwrite: Look back in your memory. Think about a time you got in trouble, were injured, were angry, were happy, etc. Now write down what happened. This is a no-nonsense summary of events.

When I was in 7th grade I wrote stories back and forth with a classmate and friend. These stories tended to be pretty gross depictions of comical sexual acts and explosions of bodily fluids. This is pretty standard stuff for hormone-addled middle school boys. I know this because I teach 7th graders. Oh wait, this is supposed to be no-nonsense.

I wrote a gross note to a friend. My English teacher confiscated it and I went to the principal’s office. I had to read it to my parents, apologize, and write an apology note.

Katlyn sets our purpose for reading (an excellent technique). What details stick out to us?

The section she reads is amazing. Dahl presents a truly grotesque depiction of a mean-spirited candy store owner. He knows how to zoom in on a key detail and then twist it into a disgustingly wonderful description. Dahl is also adept at immersing the reader in the memory and then sliding out of it to address the reader in a more authorial fashion. We discuss what we notice. Voice, point of view, hyperbole, characterization, and perspective are all mentioned. This is our first draft reading.

After she finishes we read the section again ourselves. At what point do we question the truth of Dahl’s writing? What images stand out? Is it okay if he’s not telling the 100% truth in his memoir? Katlyn comments to us that middle schoolers have a much harder time believing the veracity of every word or phrase, whereas adults don’t. Our conversation about truthfulness in memoir becomes wonderfully complex. Personally I believe that exaggeration and detail-massaging are not only acceptable techniques in a memoir but are essential to crafting an interesting narrative. It’s possible to tell the truth of the moment without being 100% factual, I think.

Now we return to our original quickwrite and look for details.

I wrote a gross note to a friend. It was funny! My English teacher confiscated it and I went to the principal’s office. He grabbed it from a kid. I had to read it to my parents, apologize, and write an apology note to the teacher. I got in trouble. It was embarrassing.

Katlyn puts up the following organizer to help us pick out details to stretch, and then stretch a lot. We’re looking for specific details to exaggerate. This is a great way to help children begin seeing writing as a series of rhetorical decisions. You can see the way she exaggerates and then hyperbolizes the facts.

Here’s mine!

-The note was gross ->

-The note was the stuff of schoolyard whispers. ->

-The crumpled paper oozed/was soaked the blunt, comical perversion of early adolescence.-My friend sat on the other side of the room. ->

-I could barely see Jackson’s flat top across the tiled expanse of the class. The note had to travel quite a distance to reach him. ->

-As Jackson and I sat on opposite sides of the room (a familiar teacher tactic for dealing with disruptions), our notes had to travel the precarious distance of the entire length of the room.-The teacher was watching us. ->

-His eagle eyes scanned the crowd for morsels. ->

-The teacher’s eyes swept over the class like searchlights hunting down an escape prisoner.

I realize that I exist in the hyperbole zone. This is my truth, the way my brain perceives and processes things. This makes sense with my earlier position on being liberal with the ‘truth.’ Oh, this is just so much fun. It really makes you focus on the purpose of every word. What choices would a journalist make? What about a comic? How do expectations about audience play into word choice? It’s probably best to finely tune the writing so it’s not either 100% over the top or 100% dry. Katlyn ends her presentation with a couple samples of student work.

Outstanding!

How Do I Write? Exploring Your Writing Process – NVWP Summer ISI – Day 2

Welcome to the Northern Virginia Writing Project’s 2016 Invitational Summer Institute! I’ll be blogging the demonstration lessons and the various activities occurring during our four-week duration. Find out more about the NVWP and the National Writing Project.

Sarah Baker, O.F.L., leads us through her demonstration lesson exploring the various ways we write. Community builds confidence. Confidence builds ownership. Ownership builds resilience. Resilience, we hope, will get us to success. Most of her teaching is online. She’s going to have us explore who we are, how we write, and the fruitful connections between.

We begin by writing down three adjectives that describe our attitude toward writing in an academic environment:

Eager – Unworthy – Exhilarating

Others offer adjectives such as: fearful, unwilling, imperfect, familiar, anxious, exhausting, challenging, reflective, emotionless, uninspiring

We all have feelings about this stuff. So do our students. That’s the point. This sort of quick exercise helps us take the pulse of the class. This short activity can provide startling windows into each student.

Time for a freewrite: what animal is your writing?

Since this is a free-write I’m trying to write without stopping. So the first thing that pops into my mind is a sort of two steps forward/one step back motion. A recursive process that makes progress only by frequently doubling back on itself. So maybe I should go with a hermit crab. My home is the recursive shell, a cyclical structure suggesting labyrinthine corridors and inward direction. Like hermit crabs my writing often moves slowly. I have a habit of writing multiple sentences about one thing in quick succession. Ok write write write, remember, in a freewrite you don’t stop writing until the time is done.

Our animals/creatures are giraffes, octopi, ladybugs, stingrays, three squirrels, and bats, to name a few. Now apply this to writing. What does your piece of writing want to become? Our writing changes. We change as writers. This is something you can come back to and get different results.

Now let’s take it a step further. Recall Betty Flowers’ influential article on writing roles: architect, madman, carpenter, and judge. Who are the characters in your head when you write? Who’s living up there?

The Judge

The Spaz

The Fiend

The Silencer

The Exhibitionist

Others come up with:

It’s amazing how much stuff we have to say about writing based on such deceptively simple prompts. Although we haven’t produced much in the way of words on the page, our meta-cognition is off the charts. Who gets to drive the process? We have control, but we often forget this when wrapped up in the potentially torturous task of writing.

We next draw our writing process. Here’s mine. You’ll notice themes of recursion, continuity, linearity, and containment.

After hearing a few others share out, I realize I did it wrong. I was meant to do an illustration of my actual writing process. It’s pretty simple: coffee, a fresh pack of gum (I refresh the piece every 5-10 minutes), and complete silence. I sit down and write in shotgun blasts that I then go back and try to make sense of. Connect, delete, edit, revise, etc. And I repeat that until I’m too lazy enough to keep working on it.

Additional Readings:

Wyche–Time Tools Talismans is a fantastic discussion of the importance of understanding our writing process.

Know Your Theory! – Process Composition Pedagogy Edition

This series of blog posts will provide an overview of the composition field’s relevant pedagogies. These posts will draw mainly upon A Guide to Composition Pedagogies by Gary Tate et. al. The book is divided into chapters based on the different pedagogies. The breakdown for each post will be around 1/2 summary and 1/2 my own reflections, analysis, anecdotes, and commentary. Although I’m writing these posts to help myself process through and reflect upon the field of composition, it’s my hope that any teacher of writing can find something of interest. Part 1 addresses collaborative writing pedagogy, part 2 explores critical pedagogy in the writing classroom, part 3 describes expressivist composition theory, part 4 examines feminist composition pedagogy, part 5 concerns genre composition pedagogy, and part 6 looks at literature composition pedagogy.

Process Composition Pedagogy

I write in a scattershot format. I start out by writing out key concepts and interesting phrases on a blank document. Then I flesh out each concept, move things around, and try to let a structure reveal itself. My goal is to expand each concept and idea until it organically dovetails with what comes before and after. This requires a lot of hemming and hawing, indecision, and general consternation. At the bottom of each document I keep a “Misc. Ideas” section where I dump seemingly random thoughts. By the end my hope is that each paragraph and section successfully bleeds into the next, creating a narrative thread that ferries the reader along from point to point. I didn’t realize this until someone asked me to describe my personal writing process. With that in mind, this final post in the Know Your Theory! series describes process pedagogy. How do writers write?

I could reduce every composition theory explored in this series to a value statement. For example feminist composition pedagogy uses writing to address and achieve social justice in the classroom. Genre pedagogues bring attention to the different ways genre shapes our perception of and interaction with various forms of literacy. Each links writing with a goal larger than the writing itself. This is not the case with process pedagogy. Process pedagogy uses knowledge about how students write in order to improve student writing; writing is both the subject and the object. The idea behind process pedagogy is simple to understand: focusing on how we write improves what we write. The simplicity of the idea belies the semi-radical nature of process pedagogy. In order to understand that we need a glimpse of what was happening on the composition scene before the process movement kicked off.

The Spectre of Traditionalism

As an inner categorizer, my natural inclination is to reduce everything to discrete units so I can slot them into the appropriate categories. I also have a penchant for periodization. Many of my frustrations about trying to understand the composition field stem from my (and the field in general’s) inability to offer up a formalized chronology of major events. Even if I could cobble together some sort of linear history, the sequential logic of A -> B -> C ignores the complex vertical negotiations between institutions and teachers that bubbles and froths below any orderly history.

Ever since its beginnings at a Dartmouth College Seminar in 1966, process pedagogy has loomed large over the field of composition. It offered an appealing challenge to current-traditionalism, the dominant paradigm of composition instruction at the time. In order to understand the widespread appeal of process pedagogy, it’s first necessary to explore the methods of current-traditional instruction. My writing about current-traditionalism is in the present tense because it still lives on in many classrooms across the country. I say this not to disparage teachers but to point out that what we do in our classrooms often borrows from different bodies of theory at different times. Restricting yourself to a single theory is myopic and limits your ability to reach a diverse population of learners.

Current-traditionalism (CT), called so because it brings traditional beliefs into current classrooms, is defined as “formulaic notions of arrangements; an inflated concern with usage and style…no discussion of drafting, and a focus on grammatical and mechanical correctness.” Students in a CT classroom can expect to practice writing in the dominant modes of expository, descriptive, narrative, and argumentative. In terms of assessment and end goals, CT measures student writing against well-established pieces of professional writing. Compared to professional and published writing, student compositions naturally come up short. Since CT views writing as the combination of parts (thesis statement, topic sentences, concluding sentences) and axiomatic rules (avoid sentence fragments, watch out for comma splices, don’t split infinitives), creating a polished piece of writing means attending to the mechanics and usage of established grammar and genre.

A CT approach views writing as an assemblage of knowable parts. Take the paragraph, for instance. Current-traditionalism borrows its definition of the form and function of a paragraph from Alexander Bain’s seminar paragraph definition of 1866. Don’t be fooled by the archaic date and unfamiliar name; Bain’s definition of the perfect paragraph continues to hold sway. The picture below is a page from one of the many writing textbooks in my school’s English rooms (Write Source: A Guide for Writing, Thinking, and Learning).

Paragraphs should be written as mini composition in which every sentence must fall under dominion of the powerful and guiding introductory topic sentence. I mention the paragraph for two reasons: to highlight the ways current-traditionalism lives on in English classrooms and to provide a minor peak into the world of English textbooks (For a fascinating look into the ways textbooks have influenced English check out Textbooks and the Evolution of a Discipline by Robert J. Connors).

Much like every other composition pedagogy I’ve covered throughout this series of posts, current-traditional pedagogy is no one thing. It’s marked by the struggle “between stasis and change” that characterizes all pedagogy. Mentioning CT’s status as a pedagogy-in-flux is important because it’s often viewed as a calcified set of beliefs and practices which no longer serve any instructional value. It’s also worth noting that teachers who employ pieces of current-traditional pedagogy are certainly not “bad” teachers. The more I learn about composition studies, the easier it is to understand why many K-12 English Language Arts teachers implement a variety of writing strategies, some in contradiction with each other.

From Product to Process

The above image (from A Guide to Composition Pedagogies by Gary Tate et. al.) sums up the changes between current-traditionalism and process composition. The ideological assumptions behind the process approach “represented an important shift in priorities, attitudes, and the use of class time.” Process pedagogy places a focus on the process of writing, on the various methods and strategies real writers employ to create a piece of writing. We’ve already discussed a few reasons why this change was so monumental.

Early process approach split the writing process into three main components. Donald Murray’s landmark essay Teach Writing as a Process, Not Product suggested the tripartite structure of prewriting, drafting, and revising that continues to hold sway today. While certainly not new (classical rhetoric’s five-part canon includes invention and arrangement), spending instructional time on prewriting and content generation before drafting was an important break from tradition.

The rise of process pedagogy paralleled newfound interest in the composing process of the student writer. Educators like Janet Emig, (The Composing Processes of Twelfth Graders), Nancy Sommers (Revision Strategies of Student Writers and Experienced Adult Writers), and Muriel Harris (Composing Behaviors of One- and Multi-Draft Writers) produced groundbreaking scholarship investigating the ins and outs of the composition process. How do students approach a new piece of writing? How do they move between writing process stages? How do the moves made by students and expert writers compare? Thanks to these and other efforts, we know that good writing requires copious amounts of revision, and that beginning writers spend the least amount of time on revising and editing. Process scholars have also helped illuminate the complex situational variables that inform how a student approaches a piece of writing. Location, purpose, audience, genre, and mindset are just a few of the factors that affect student writing. The fact that these ideas may seem obvious to us now is a testament to the near hegemonic influence of the process pedagogy movement.

Criticism and Push-Back

As with all schools of theory, early incarnations of process pedagogy were refined and rebalanced by academics and practitioner-scholars. Many of us might remember (or use) some form of a process wheel in our classes. We now know that there is no one process. Expecting students to move from prewrite to publish in a linear fashion misses much of the point of process pedagogy. For this reason later theorists stressed the recursive nature of writing.

Composition’s social turn, a move in the late 1980s/early 1990s to reorient the field to include issues of culture, ideology, and sociality, reminded compositionists that when it comes to writing, culture matters. Any effective English teacher must account for cultural differences in how children, families, and schools when planning for student writing. In Other People’s Children, Lisa Delpit offers a scathing critique of progressive teachers who engage children in peer critique and brainstorming while ignoring direct skills. Her book is a poignant reminder of the importance of a balanced approach to literacy.

Chances are if you teach English you’re familiar with some process pedagogy. Major education publishing houses like Heinemann produce scads of professional materials devoted to helping children flesh out ideas, revise drafts, and edit for standard grammar and punctuation. That’s why I’ve left the actual classroom component of this post until the end. I wanted to contrast process pedagogy with current-traditionalism because I think there’s incredible value in understanding where we come from.

This is my final post in the Know Your Theory! blog series, and I hope you’ve enjoyed reading them.

Additional Resources Consulted:

Current-Traditional Rhetoric: Thirty Years of Writing with a Purpose by Robert J. Connors

Process Pedagogy by Lad Tobin

Coherence in Paragraph-Level Structures by Marc Pressley

Know Your Theory! – Collaborative Writing Pedagogy Edition

The National Writing Project is an amazing thing. I’ve been fortunate enough to be a part of the Northern Virginia chapter of the Writing Project’s Invitational Summer Institute for the last couple of years. The Invitational Summer Institute is an intense four-week experience where educators get together to talk about all things writing. I’ve transitioned from completing the program (becoming a Teacher Consultant in the process) to co-directing the four-week institute.

For this summer’s ISI I’ve appointed myself Theory Czar. To that end I’ve flung myself into the exciting realm of composition theory. This new series of blog posts will provide an overview of the composition field’s relevant pedagogies. These posts will draw mainly upon the excellent A Guide to Composition Pedagogies by Gary Tate et. al. The book is divided into chapters based on the different pedagogies. The breakdown for each post will be around 3/5 summary and 2/5 my own reflections, analysis, anecdotes, and commentary. Although I’m writing these posts to help myself process through and reflect upon the field, it’s my hope that any teacher of writing can find something of interest.

Know Your Theory! – Collaborative Writing Edition

The first post in this new series discusses collaborative writing pedagogy. Simply put, collaborative writing theory attempts to explain the benefits, pitfalls, and rationale behind asking students to write together. The chapter begins with a reference to the model of solitary authorship promoted during the Romantic era (late 1700s to the mid 1800s). This is when many colleges in the United States began offering coursework in composition. Consider the Romantic trope of the tortured artist toiling away in isolation, producing masterworks out of his or her suffering.

The notion that a text is the result of a single author persisted in composition pedagogies until poststructuralist theorists like Michel Foucault infamously heralded the “end of the subject.” This stuff gets complex pretty quickly. In terms of collaborative writing pedagogy, all we need to know about the advent of postmodernism is that we no longer understand a text as a freestanding object created by a single person. Writing is always an act of collaboration. The chapter offers the following strategies for thinking through collaborative writing assignments in the classroom.

Delay Students’ Collaborative Writing:

Collaborative writing is difficult and should therefore not begin until the school year is well under way. In the time leading up to the task of collaborative composition, be sure to implement a plethora of social constructivist tasks: group work, peer review, class discussion, and even collaborative revision. It’s also worth mentioning that although every class benefits from community building activities, any teacher with her eye towards collaborative writing should invest a significant amount of instructional time on developing strong interpersonal relations and a positive class identity.

Design the Assignment for a Group, Rather Than Redesigning an Individual Task:

A mistake I’ve only recently begun to remedy in my own practice is the art of creating and assigning effective group work. Tasks given to a group need to be designed for a group. This means a significant increase in difficulty: for instance tasks that are labor intensive, require specialization, and/or involve deep levels of synthesis. The collective brainpower of the group means a higher zone of proximal development. A higher ZPD should mean more difficult tasks.

Discuss Methods and Problems of Collaborative Writing before the Project Begins:

Spend time ‘pulling back the curtain’ on the the basic methods and common pitfalls of collaborative work. This means discussing power dynamics based on race and gender (i.e. females doing all of the work). Go over consensus-building strategies as well as ways to help students actively listen to each other instead of resorting to adversarial majoritarianism.

Choose the Type of Collaboration:

The authors mention dialogic and hierarchical collaboration. Dialogic work involves students working together on every aspect of a project, whereas the latter involves breaking a task down into discrete components and assigning each part to a different group member. Dialogic work brings with it all the joys of messy discovery; hierarchical methods are more efficient and timely. Many types of collaborative writing require an interplay between dialogic and hierarchical teamwork.

Anticipate Problems:

Working collaboratively leaves us open to the reality of rejection. As one of my old bosses used to say, “Rejection of your ideas does not mean rejection of you as a person.” This is tough enough for anyone to do, regardless of age. Talk to students about this.

Anticipate and Prepare for Student Resistance:

Many students oppose group work. In my limited experience, I think much of this resistance is the result of unchecked power dynamics. “I’m the one that ends up doing all the work,” is a common (and valid) refrain. And some students do their best work when writing in isolation. It’s your job as the teacher to decide when to require group work. The chapter recommends helping students see how prevalent collaboration is in the work world, how individual writing improves from having worked with others, and how thinking through complex tasks with others typically increases understanding for everyone.

Let the Class Decide How the Groups Will Be Constituted and Discuss the Pros and Cons of Each Possibility:

Grouping students for successful collaboration is tricky. Students, like anyone, want to work with their friends. It’s important to stress to your class that while everyone enjoys working with people they know and feel comfortable with, doing so can leave certain students feeling unloved and unwanted. Additionally, we live in a world of others. It’s our duty to make sure students have the tools necessary to work successfully with all manner of individuals.

Give the Groups Autonomy in Deciding Their Methods and Timetables:

Creating and adhering to schedules and milestones is both essential to healthy collaboration and a key component of self-management. It’s important to devote class time to helping students through this process. As always, never assume that students know how to do these things.

Prepare for Dissent within the Groups and Prepare to Manage It in Two Dimensions: The Instructor and the Students:

The authors explain that successful collaboration allows for group cohesion, creative conflict, and the protection of minority views. Welcome rather than dread dissent. Tell students to anticipate in advance the presence of conflict and to welcome it as a sign of creativity and generativity. Handling dissent will require the direct instruction, scaffolding, and modelling of specific strategies. The authors recommend pulling from the academic traditions of “counterevidence” and “minority opinions.” Managing disparate ideas effectively is a great way to practice thesis, antithesis, textual evidence, etc.

As common sense as collaborative writing seems, I must admit I do remarkably little of it. I think there are probably many reasons for this: a culture that uses competition to pit students (and teachers) against one another, our education system’s strain of individualism, the difficulties of interdependency, and the challenges of devoting class time to something that won’t explicitly show up on a high-stakes exam are but a few examples. However collaboration has never been easier. Something as simple as a shared Google Doc allows multiple authors to work on a single text with only a few clicks. A cursory internet search yields a plethora of decent, free resources to help students work together. Although I’m not entirely convinced that collaborative composition is robust enough to carry the theory/practice weight of a full-blown pedagogy, the ideas presented in this chapter are certainly worthy of thought and implementation.

X -> Y: Peter Elbow’s (Still) Revolutionary Developmental Approach to Writing

Peter Elbow’s Writing Without Teachers (1973) caused me to radically rethink my approach to teaching writing in the classroom. The book offers a method of improving your writing that doesn’t involve direct and constant intervention of a teacher. Crazy, right? Real growth comes from modifying your work based on how average readers experience your words. Average here has nothing to do with quality. The well-trained and sympathetic writing teacher is an ideal, and therefore unhelpful, reader. By knowing you and the assignment and the classroom setting, the feedback she provides, while useful, is divorced from the reality of the reader-writer relationship. This means no more mini-lessons on adding supporting details, developing topic sentences, etc. Writing isn’t something that can be broken down into discrete parts and taught. It lurches forward, improving and declining in uneven steps.

The book begins with the Elbowian approach to free-writing; a section awesome enough to warrant its own post. Elbow divides the rest of the book into three sections: writing as growing, writing as cooking, and the teacherless writing class. This post will cover the main points in each section. It’s my hope that you find the information contained in this book as useful as I did.

Writing as Growing

The first section opens with a brief discussion of the way most of us conceptualize the writing process. The traditional method of composition has at its core the notion of ‘control,’ exerting control over words, ideas, and organization. This translates into a process that begins with a clear, predetermined idea and works towards it with workman like efficiency. Anyone who has taught writing knows this model well. (As a side note, this traditional model finds an excellent contemporary analogue in Katie Wood Ray’s Inquiry model.) Get your ducks in a row and outline your major points before drafting. Elbow argues that this method of writing is backwards. Writing should be approached organically, he says. We should write before we even know our meaning; our words and ideas will gradually change and evolve as we write. Think of writing not as a way to transmit an idea but a way to grow an idea. A transaction of words that frees yourself from what you presently think and feel by giving up control.

Stop and take a second to let that sink in. I had to, at least.

This throws into question the entire enterprise of writing as a mere record of learning. How often do we write a draft and then fix it up? This one-and-done approach leads to half-baked ideas that, while perhaps grammatically and syntactically sound, lack any real assertion or vitality. We write something and then spend hours banging our heads against it. Elbow argues that this doesn’t work. The phrase ‘you can’t polish a turd’ comes to mind. We must push ourselves and our ideas to grow. How do we do this? While the book’s method is of course nuanced and multifaceted, I’m going to try and reduce it to the following steps:

Elbow’s Basic Approach to Growing

1. Write down everything you know about your topic (or subject or feeling or memory or idea or just whatever is sitting on the top of your brain). Don’t stop. Follow every digression and tangent.

2. Go back over what you just wrote and figure out what it wants to say. Make it say something. Reduce it to sentences that can be quarreled with. This process of summing-up should be difficult; you should learn something more than you already know.

3. Take your assertions and begin a new draft with them.

4. Repeat.

You believe X. While writing about X, you begin to realize that you actually believe in Y. This is a process of writing, summing up, and rewriting. Do this multiple times until a center of gravity begins to pop out. The developmental approach functions by way of a dialectic. It’s the interplay between writing and summing-up that moves the writing forward, not the adherence to a predetermined thesis. Elbow explains that while the developmental approach might be more work, the work involved is more productive. Think about writing as “successive sketches of the same picture, each one getting clearer, more detailed, and better organized.”

Writing as Cooking

Cooking is the term Elbow uses to describe the way writing needs to interact with others. Material is transformed through the generative interaction between multiple people, conflicting ideas, and different perspectives. Writing must be cooked -seen and reflected through the lens of others- in order to reach excellence. Cooking describes how we improve our writing by successively climbing on the shoulders of the way others see our text.

The basic approach to cooking

1. Allow others to read your writing. Do not give an intro or explain anything. No self-flagellation.

2. Every reader will describe the effect your writing had on them. How did it made them feel and what did it made them think of? The key here is that they respond as READERS, not students in a writing class picking at grammar or spelling or making suggestions.

3. The writer simply listens to each reader’s response. The material needs to cook and mix. Arguing with someone’s reading produces nothing but a stalemate. Ideas need to procreate, not lock horns.

4. Embrace disagreements and misunderstandings as the primary way to rethink your draft.

Summing up Cooking and Growing

Cooking means getting material to interact. The interactions most important to Elbow are the interactions between writing and summing up. Working in words and working in meanings. Growing means getting words to evolve through a series of stages.

The Teacherless Writing Class

According to Elbow, improving your writing has nothing to do with learning discrete skills or getting advice about what changes you need to make. This stuff doesn’t help. What helps is understanding how other people experience your work. Not just one person, but a few. You need to keep getting it from the same people so they get progressively better at transmitting their experiences while you get better at receiving them. How do we do that?

Advice to readers

-Point to specific words and phrases which “penetrate your skull” and explain.

-Summarize what you feel to be the main point(s), feelings, and centers of gravity.

-This isn’t a test to see if you understood; it’s a test to see WHAT you understood. This is an important distinction.

-Tell the writer everything that happened to you as you read the piece.

-Talk about the writing metaphorically: weather (foggy, sunny, gusty, etc.), movement (marching, climbing, crawling, etc.), clothing (jacket and tie, miniskirt, slicked back hair, etc.), musical instruments, animals, vegetables.

-Give specific reactions to specific parts.

-No kind of reaction is wrong. You are always right and always wrong.

Advice to writers

-Be quiet and listen.

-Don’t reject what readers tell you.

-Listen to they say it just as much (if not more) than what they say.

-Don’t be paralyzed by what they say. It’s their job to give you their experience. It’s your job to figure out what to do next.

Final Thoughts

This process of writing and sharing and improving takes many months. Be bold. Read out loud; don’t fear anything. Fear is the biggest impediment to good writing. When writing, alternate between between working things out in the medium of ideas and the medium of words. Engage every tangent and digression. Work every idea out to its extreme conclusion; explore every meaning and definition and direction until a center of gravity begins to occur. Writing without stopping is central to the developmental method. We can’t censor or alter or prejudge our words and ideas; we simply write them down and keep going. We can’t expect our best writing -or even good writing- in the initial stages. It’s crucial to understand that many of the words you write, perhaps all of them, may roll of the pencil feeling sour or wrong. Give yourself permission to write this way. Then, come back and pick out any words or phrases that seem to work. Don’t be hypnotized by your own writing. Kill your darlings. Editing occurs only at the end. Becoming a better producer allows us to become a better editor. Be ruthless as an editor. Cut out all dead wood. Arrange the words into a unified structure.

I love how the process described in this book changes the power dynamics in the class by restructuring authority away from the teacher and investing it back into students. I’m excited to use this approach in the upcoming school-year!

Just Don’t Stop! A Brief Explanation of Freewriting

Just Don’t Stop! A Brief Explanation of Elbowian Freewriting

How many times have you asked your students to do a freewrite? Do you use the terms ‘quickwrite’ and ‘freewrite’ interchangeably? This brief post attempts to provide a working definition for freewriting. That way, you can make sure you’re using this powerful technique correctly (or at least how its creator imagined it).

The man himself!

English education scholar Peter Elbow published his first book, Writing without Teachers, in 1973. It is amazing. The book captures Elbow’s ideas on writing, composing, and responding. The ideas contained within his debut are as exciting now as they were forty years ago. The developmental approach to composition Elbow develops throughout the book stands in stark contrast to the way many of us teach writing to our students. I hope to address the book in a future post. For now, let’s dive in to what the master has to say on the topic.

What is freewriting?

Freewriting, also known as ‘automatic writing,’ is a technique that asks the writer to compose without stopping. That’s it. The goal is to sit down and pour out whatever’s on the top of your brain for ten to fifteen minutes. Without stopping. Freewriting is lowstakes; it’s not to be read or evaluated by anyone but the author.

Did I mention you shouldn’t stop? Go quickly. Never stop to look back or cross something out. Your pen/pencil/keystroke should be moving forever forward in time and on the page. Can’t think of how to spell a word? Fudge it. Don’t know what word to use in a sentence? Draw a squiggly line and come back to it when you’re finished. If you get stuck write, “I’m stuck” over and over until your ego gives up control and lets your subconscious take over. I can say from personal experience that this is perhaps the most essential (and difficult) component of freewriting for students to master, IMHO.

What ego?

Schooling makes us obsessed with our mistakes. This means our internal editor is always on the hunt for anything that isn’t perfect. Our ego makes sure to leave out any idea or phrase it deems too silly or not good enough. Editing by itself isn’t the problem; editing is a necessary part of the writing process. The problem occurs when editing goes on at the same time as producing.

Producing while editing in the moment creates stilted prose.

The main thing about freewriting is that it is and must be inherently nonediting. Regular freewriting practice undoes the ingrained habit of editing while composing. It allows our first thoughts to come up and live on the page. The goal here is to TRY to get into a flow by getting out of the writing’s way. It won’t work all the time. It shouldn’t work all the time, really.

That’s it. I’ll devote more time to the entire book in an upcoming post. It’s that good.

Let’s end this brief post with a quote from the book.

“If you do freewriting regularly, much or most of it will be far inferior to what you can produce through care and rewriting. But the good bits will be much better than anything else you can produce by any other method.”

You can find a pdf of the freewriting section of Writing without Teachers here.

For more on our internal editor please refer back to my previous post on various ways authors approach the writing process.