Category: Poetry

Speaking Your Truth Through Slam Poetry: A Unit Overview

“We’re doing poetry? I haaaaaaate poetry! It’s SO boring, Mr. Anderson!”

One of the easiest ways to make a room full of middle schoolers groan is to say the word “poetry.” I don’t blame them. The thought of analyzing the theme of “Hope is the Thing with Feathers” or any of the other nature themed poems that regularly pop up on standardized tests makes my eyes slide back inside my head.

A few years ago I began teaching a unit on slam poetry. Students responded immediately to slam poetry’s relevance, topics, and overall style. Slam poetry feels vibrant and current. And thanks to the internet, teachers now have access to cutting edge slam poetry written by people that look and sound like their adolescent students. I’ve taught this unit three years in a row, and it never fails to produce some of my students’ strongest writing of the year.

What follows is my basic blueprint for my annual slam poetry unit. This unit combines “just right” mentor texts with rock solid instructional activities. Because it requires students to be vulnerable, I typically save the unit for the back half of the school year. That way I’ve had time to build and sustain a sense of classroom community with students. Without vulnerability, slam poetry is nothing.

Unit Title: Speaking Your Truth through Slam Poetry

Time Length: Five weeks of 42 minute class periods

Final Product: Students will write, revise, and submit an original slam poem. While students do not have to present, they are encouraged.

Standards: These are from Virginia. I’m sure most states/Common Core have something similar.

- describe the impact of word choice, imagery, and literary devices on different poems (7.5d)

- analyze the themes of various poems (7.5a)

- write, revise, and edit original poetry that that incorporates word choice, imagery, and literary devices (7.7d, g, j)

Mentor Texts: Ten years of teaching English Language Arts has taught me that providing students with engaging, developmentally appropriate, and culturally responsive mentor texts from the “real world” is the most essential component of a successful unit. To that end, I’ve collected every slam poem I’ve ever used into a mentor text packet for you to make a copy of. Every poem in this mentor text packet has a corresponding YouTube video of the poet delivering (or ‘slamming’) their poem.

Content Warning: If you plan on using these poems, make sure you read through them first. For some of the poems I give a content warning and provide students with a chance to sneak out first. The poems here deal with topics such as: anxiety, depression, grief, ADHD, race, gender, substance abuse, technology, and religion.

Basic Instructional Sequence: The basic instructional sequence for this unit is adapted from the mentor text model described by Katie Wood Ray in Study Driven. Students begin by “immersing” themselves in slam poems. They listen, discuss, read, and write. The next step asks students to “write under the influence” of the mentor texts. Finally, students use specific texts and techniques to revise and deliver their poems.

Immersion Phase: Expose to students to the mentor texts. Get them reading, writing, and talking about them.

- Introduce the genre with a high interest slam poem (You can never go wrong with Touchscreen). Help students identify the difference between first and second draft reading. The former helps students access the content (the WHAT of the poem) while the latter gives students a way to analyze the craft moves made by the poet (the HOW of the poem).

- Introduce one poem a day to students. Watch them multiple times. Read them multiple times. Give students room to respond to the poems in a way that suits them. This is where I introduce “punctuation annotations.” Students read through the poems and mark up the lines with hearts, exclamation marks, question marks, etc. What surprises them? What lines can they identify with? Etc.

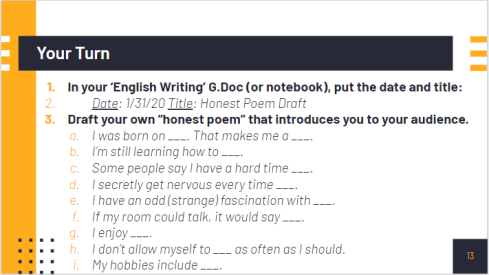

- Then, have students use the basic framework of the day’s poem to generate their own version. The goal here is to give students their own bank of writing to draw from when it comes time to commit to a draft. I always give students two options. They can just “go for it” and write something with the mentor poem on top of their brain. Or they can use a “poem frame,” a more sophisticated fill-in-the-blanks. This requires the teacher to use a poem with an easily identifiable and copyable format. Below is one of the slides I used from the excellent Honest Poem by Rudy Francisco. The bullet points on the slide come from lines in the poem that I adapted.

- Students end this phase filling out a simple “What is slam poetry?” handout. It has four basic questions about what slam poetry is, how it’s different from more traditional forms of poetry, and what they can write about for their own poems. Students have immersed themselves in slam poetry for about a week at this point, so there isn’t much scaffolding or direct instruction that happens here.

Writing under the influence: Students use the mentor texts as guides to help them write their own poems.

- The goal of this short phase is for students to complete their “down draft.” To just get something “down” on the paper. We’ll fix it “up” in the next phase.

- Students are encouraged to “talk back” to any ideas or stereotypes others might have about them. I typically introduce this idea by asking students to tell me what they assume about teachers. That we have no lives. That we live at school. That we hate kids. You can spend as much/little time with this as you want.

- Students can use any of their poem quick writes from the previous classes.

- Students can practice “lifting a line,” a simple technique where students pick a favorite line from a poem and use that to either begin or end their own original poem.

- I try to help them focus on quantity instead of quality at this stage. I shout “JUST WRITE!” a lot during this time.

Using Mentor Texts to Revise and Polish: This is where the real work comes in! Now that most students have a workable draft, it’s time to begin the labor intensive process of revision.

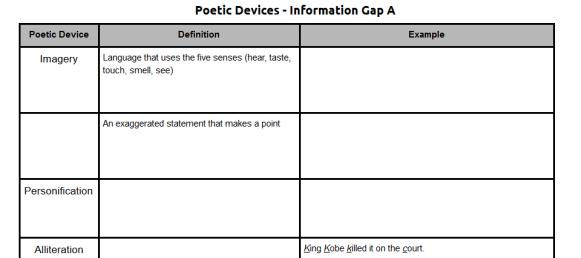

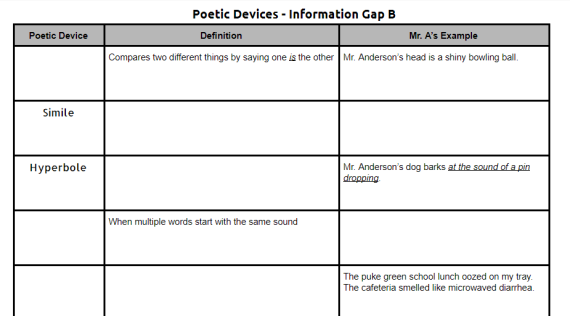

- To make sure we’re all on the same page with language, we begin this step by tabling our drafts and diving into language with an “information gap” activity. Students partner up, sit back to back, and try to fill in the blank spaces on their handouts. While each student has the same information on their sheets, the blank spaces are different. Since they can’t look at each other’s sheets, they have to do a lot of talking and thinking to complete their sheet. The student’s partner would have the B sheet, the mirror opposite of A. The order is different. That way students can’t just go “what’s the 2nd box on the first line.” Here are a few lines from the two different sheets so you can better visualize what I’m talking about.

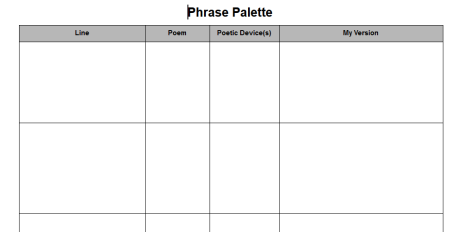

- Now that students have a resource they can turn to for figurative language, it’s time to dive into the language of the poems. I ask students to complete a “phrase palette,” a simple organizer where students copy down lines they love from our mentor texts, figure out what (if any) figurative language is going on in the line, and then try to copy it for their own slam poem. This is always harder than I think it will be, so plan accordingly. Here’s what it looks like blank.

- Once this is done, students fix up their drafts by revising their language. They use the information gap and phrase palette to help them. This is also when I do most of my individual conferring.

- The final step in this phase involves adding some killer rhymes to our poems. We begin by checking out/annotating/choral reading the best rhymes in the mentor texts we’ve been using. I do a short mini-lesson on inner and outer rhymes. I show them rhymezone.com. And then I give the class the first line of a poem about going to school. I tell them to write the next three lines of the poem, paying special attention to adding inner and outer rhymes. The key here is using a first line that has a lot of simple words to it. For instance, students had a lot of fun coming up with rhymes based on this first line: “I woke up, put some clothes on, and walked out the door.”

Presentation: Practice, practice, practice!

- To get ready, students read to the wall (your ears and eyes catch mistakes your brain misses), read to each other, record and listen to themselves reading, etc.

- I don’t do a lot of peer feedback because it’s an incredibly challenging skill that requires months and months of intentional practice. In my experience, students usually just pick at surface errors in each other’s writing. Afterall, this is what their teachers usually do to their work. The problem is that this doesn’t improve writing at all. It just makes folks not want to share.

- On the final day, I’ll throw anything and everything at kids to get them to present. Candy, extra points, names on the wall, whatever. We clap, hoot, holler, and snap every time we hear a great line.

Phew! That’s it. Like I said earlier, this unit produces amazing writing from my students. Many of them reference it as their favorite unit during the end of quarter/year reflections.

I put together a sparse Google folder with all of the handouts I referenced above. Feel free to take, copy, modify, whatever!

Found Poems: A Generative Pathway to Meaningful Textual Transactions– NVWP Summer ISI – Day 7

Welcome to the Northern Virginia Writing Project’s 2016 Invitational Summer Institute! I’ll be blogging the demonstration lessons and the various activities occurring during our four-week duration. Find out more about the NVWP and the National Writing Project.

Anna Foster is now going to take us through a demonstration lesson on the power of found poetry.

Anna Foster is now going to take us through a demonstration lesson on the power of found poetry.

Quickwrite: How do you feel about teaching poetry to students?

I’ve written about this before, but poetry isn’t my favorite. I’m a maximalist. I want long sentences, massive paragraphs, and all-encompassing narrative arcs. I like to dive into a world that has its own sense of gravity and immutable rules. While poetry might have that, it doesn’t for me. It’s just too short.

But I love teaching it. I spent the final weeks of the school year working with students on a variety of poems. Reading them, listening to them, annotating them, writing them. Poetry allows a slightly easier entry into literacy than writing a short story or a memoir.

We share out. An ESOL teacher talks about how using poetry with beginning language learners can be difficult. But once the students get that basic language down, she continues, it becomes a function of liberation. Someone else mentions how often we turn to what Paul Thomas calls the literary technique hunt. We use it for analysis more than writing, someone says. While there is positivity in the room, there’s also trepidation.

Anna says that teachers can (and should be!) infusing every unit with poetry (vs. having a specific poetry unit). Poetry lends itself to essentially every literacy related skill. Especially, she says, found poetry.

What is found poetry?

The fact that students don’t have to start from scratch is a big advantage to found poetry. Modern forms of found poetry include blackout poetry, centos, and cut and paste poems. Examples are below. Found poems allow students to become readers, writers, and artists.

Anna runs us through a minilesson. As we listen to Clint Smith’s well-known TED Talk we’re going to keep track of any lines, words, or phrases that we enjoy. If you haven’t heard it, listen to it now. It’s that good. The minilesson corresponds with some awesome essential questions such as: How can language be powerful? How can silence be powerful? We watch the TED Talk and write.

Normally she would have us discuss the clip. For the sake of time we’re going to start out by generating a class list. We choose three of our selections to speak out. A listing of some of our selections are below:

-to fill those spaces

-to recognize them

-to name them

-tell your truth

-I still had to figure out my own

-silence is the residue of fear

-an affirmation that he was worth seeing

-will not let silence wrap itself around my indecision

-gut-wrench guillotine your tongue

-air retreating from your chest because it doesn’t feel safe in your lungs

-he was worth seeing

-manifest

-dignity

-your battles have already picked you

-read, write, speak your truth

-tucked under my tongue

We talk a little bit about why we chose the lines we chose. Rearrange, position language differently, shape it, make it your own. You can have students enter the words into Word Mover, a free website (and app) that allows you to easily manipulate words on a screen. Anna shows us her own creative process and encourages us to talk with students about what we’re doing and why we’re doing it. This is a great place to talk about rhetorical purpose in writing.

Here’s what mine looks like after a few minutes of tinkering. Every phrase comes from Clint’s TED Talk.

She mentions how found poetry can be a cool way to think about research (gathering qualitative research and then remixing it into found poems) as well as social justice (since the content of found poems pulls from the texts found in the ‘real world). We end by viewing some student samples of found poems from Anna’s classes. Great lesson and presentation!

Multimodal Literacy and Poetry with English Language Learners – NVWP Summer ISI – Day 3

Welcome to the Northern Virginia Writing Project’s 2016 Invitational Summer Institute! I’ll be blogging the demonstration lessons and the various activities occurring during our four-week duration. Find out more about the NVWP and the National Writing Project.

Empowering English Language Learners and their Families

Heather Jung, a Teacher Consultant through the NVWP, begins with an introduction about herself and what she’s been up to since she attended last year’s ISI. She’s given in-service demonstrations and presentations for various counties and conferences. She’s here today as part of one of our four interest groups.

English Language Learners

Continuity

Technology

Advocacy

Each interest group is tasked with investigating and reporting on the state of writing with regards to the group’s focus. To the best of my knowledge, this is the first interest group focus in years. The second member, Heather Grant, provides a similar introduction with personal updates. The Writing Project is like the best club ever.

Heather Jung runs us through a mini demo-lesson: Multimodal Literacy: Good ELL Instruction is Good Instruction. Multimodal literacy refers to making meaning through the reading, viewing, responding to, and producing with multimedia and digital texts.

Heather says that MML incorporates all of the aspects of literacy: reading, writing, speaking, and listening. We should care about MML because the traditional ways to acquire literacy skills are shifting from primarily page-based to screen-based. Foundational skills must not be lost in this shift to screen-based literacy. I’m reminded of the digital native discussion. We cannot take for granted that students are automatically familiar with technology because of their generation. Critical literacy lives within every genre and mode of media.

Quickwrite: What do you value in literacy instruction?

What a question! This leads directly into my own presentation (which happens to follow this one). Although literacy is in many ways a simple thing (decoding and pulling meaning from words on a page and making meaning by producing words on a page) But as soon as we begin to tease out the intersections of power inherent in both reading(reading what? are we reading for the narrative or against the narrative? Who gets exposed to which literary genres?) and writing (Who is writing? What are they allowed to write? Who has access to the rules of power characterizing academic discourse?) Ran out of time!

How do I teach multimodal literacy?

If you understand literacy instruction than you understand multimodal literacy. In terms of technology, work within your own Zone of Proximal Development. Students can develop literacy skills through digital social interaction (constructivism). A good way to think about teaching multimodal instruction is as adding a range of experiences and genres vs. whole-scale replacement. Digital texts provide many rich opportunities for rhetorical analysis: analysis of audience, genre, and purpose. We can submit every feature of a digital artifact to close study just like a more traditional print book.

Heather Grant now begins her mini demo-lesson on using poetry with ELLs. She opens with an intense poem she wrote from the point of view of an English Language Learner (specifically a child from Afghanistan). It helps remind us of the way language bombards and hammers children from the instant they step into a school. Learning a language isn’t linear; it arrives in waves. Academic language often takes five to seven years, sometimes longer, depending on the student.

Writing in a second language is intimidating. Teachers can make faulty assumptions about a student’s ability to read and write based on the child’s oral language (which is acquired quicker). Heather says that writing poetry can build a bridge between the spoken word and written word for our English learners. Listening to poetry helps us develop an ear for the cadences and rhythm of a culture and its language. Poetry is first an oral tradition and, like music, doesn’t necessarily need to be fully understood to be enjoyed.

The play aspect of poetry makes for a friendlier entrance point into literacy. Using only a few words to describe complex things can make writing enjoyable and build confidence. It also values personal voice, experience, and culture. Creating and sharing poems can help students not only express their heritage but it also builds cultural awareness among students of all backgrounds. As an added bonus, poetry allows a teacher to cover a wide range of state and ESOL standards.

Sorry about the shoddy image quality, today!

Heather offers us a quick flurry of poetry lesson ideas. I’m not going to type them out because there’s too much to convey in the moment. She discusses breaking apart mentor poems, studying them, emulating them, publishing them, etc. Listen to multiple readings of poems. Read it out loud with expression. Push students to respond with the heart and the gut before they begin analyzing. One of my favorite tips is to allow students to intermix their home language with English when they write.

Student Made Standards Based Rubrics – NVWP Summer Institute – Day 12 pt. 1

Now we have Nick Maneno. He’s one of the many rockstars of the Writing Project. He is a model for pretty much all of us. He apparently begins most of his emails with, “hmmm..” I think I’m going to start doing that.

Student Made Standards Based Rubrics: An Inquiry Approach to using a Mentor Text to identify standards, develop a Rubric, craft and score a poem.

What a title!

Nick begins by talking about how he isn’t really that into rubrics. But he works in a school system that uses Standards-Based Grading (want to learn more about it? Look up Rick Wormeli. He’s sort of like the guru). Nick says he likes neither rubrics nor standards, but he has to make it work. So this demo lesson is an attempt to make all of this work. Please note that this demo lesson write-up will be devoid of any authorial commentary by yours truly.

Quickwrite1: List some things you do for fun and recreation.

-reading/writing

-video games

-YouTube

-pretend to exercise

-eat

Now, pick one thing from the list and keep it in your head while reading the following poem. (An intention for reading)

Then he tells us to read it again, only this time looking for literary elements and text features. What standards do we see being used here? We discuss movement, font size changes, capitalization, onomatopoeia, author’s purpose, exaggerated spellings, non-standard use of line breaks and white space, (link here to Katie’s presentation), alliteration, strong verbs/word choice (link here to Janique’s lesson), a title (link here to Michele’s lesson), parallelism with the ‘ing’ forms, we gerunds.

We get ourselves together in groups of three. Three is the perfect number, he says. You get a diversity of opinions while still allowing a space for everyone to give their opinion. We add polysemous words, some repetition, the form paralleling the content of the poem, and more. (Nick says here that collaborating and turning and talking with partners is the most important part of his classroom. Nick gives a plug for “Teaching with Your Mouth Shut [which I’ve never heard of! Amazon, here we come]). I’ve already learned so much from just this conversation.

So we’re all noticing here. Nick shows us what his fifth graders noticed:

Nick is going to have us write our own poem using the Kwame Alexander as a mentor text.

The first step is to compose a rubric for the poem we’re about to write, using the Virginia writing standards of ‘Composition,’ ‘Expression,’ and ‘Mechanics.’ I don’t get very far. We work on our rubric individually, then we go back to our group of three and try to put it together. Nick tells us that he doesn’t really care that much about the rubric. The important part, he says, is the dialogue parsing out what it is that makes a poem successful or not. Nick ties this into the Inquiry model. Immerse students in the genre, and then have them create a rubric for what they’re about to create. Here’s the rubric Nick’s class came up with.

I am again, for the enteenth time this summer institute, reminded of Katie Wood Ray and “writing under the influence.”

Nick wants us to now write a poem emulating Kwame Alexander’s poetic form following the class’ rubric. I’ve written mine about one of my hobbies: watching Northern Lion’s YouTube Let’s Play videos after work. I do this religiously every day. I’ve been watching his videos for months, and by now I feel like part of the family. Interesting connections here with online communities, video games as an industry, YouTube as a public sphere, etc. Here’s my draft!

Now he has us ask ourselves the following questions: What did I learn by doing the rubric? Did it help me learn? To be honest, our group was more interested in gabbing about our poems than we were discussing the rubric portion. Nick then shows us a powerful slide reflecting what his students thought about the rubric process.

Next up is Essaying. Nick sets us up with a T-Chart. He calls this the Chronologic method, which I love. Chronologic writing comes from Paul Heilker. Left side is “What I think the poem is about” and the right side is “Why I think Like I do.” He then reads us a poem line by line. After each line he stops reading and we keep a running log of what we think it’s about and why I think the way I do.

The evidence falls into five categories: logic, life experiences, intuition, emotion, and text evidence. These are the five paradigms of essay writing, he says. This type of line-by-line analysis is an excellent way to promote the essay as a tool for understanding. Nick is interested in reclaiming the essay for ‘writing to learn’ instead of ‘a record of learning.’ He mentions that the French verb ‘es say’ is ‘to try.’ So he encourages us to use tentative language (instead of the authoritarian language often taught alongside the essay). Coming to understanding through stages of measured analysis and thought. After each stage the class discusses our various interpretations and reasonings. We’re encouraged to ponder each new perspective, adding it to our own if we want. The essay becomes the combination of the Chronologic thinking. Claim and evidence moving forward towards a new point of understanding.

Line and Stanza Breaks in Free Verse Poetry – NVWP Summer Institute – Day 5 pt. 1

First up is Katie Hedrick

Structuring Free Verse Poetry: A Lesson in Intentionality & Revision

Katie designed this lesson because her students struggled learning how to effectively write Free Verse poetry. Most English teachers know how quickly children (and adults!) glom onto formulaic poetry such as haiku, sestinas, etc. There’s nothing wrong with formulaic genres; indeed, working under tight constraints is an excellent way to foster creativity.

She begins talking about the idealist and the realist. The idealist is the part of her that wants to teach only lessons that she finds personally rewarding. At its best, this type of teaching helps educators tap into their own passions and bring that joy into class. At its worst, this sort of teacher-centric approach can lead to “hobby teaching,” a term describing when teachers only cover what they want to cover. Contrasting the Idealist is the Realist. The Realist is concerned with doing things simply because admin and standards and bureaucratic structures mandate them. In that sense, Free Verse poetry pops up in many high-stakes tests and benchmark assessments.

This is an interesting bifurcation. I often get the sense that many teachers carry an “I only do this because admin/test/state standards dictate it.” That if only we were free of these diversions we might be able to dive deeper into a practice that sustains us more as educators. My partner, Amber, discusses how mentioning the realist might also help with teacher buy-in by acknowledging the “but I have to do this because my _____ requires me to ____” mindset endemic in the teaching population.

Katie’s problem was that her students’ poetry resembled paragraphs more than a poem. That’s where this lesson, the intentional use of line and stanza breaks, comes into play.

At this point in the unit, Katie has already immersed her students in free verse poems. We begin by counting the number of lines in the poem, ‘Lost’ by Liam Anderson, and writing it at the bottom of the page. Then, we look at the number of stanzas. We notice (in the Kylene Beers way) things. How long the lines are, how long the stanzas are, the placement and mere existence of phrases, fragments, and complete sentences.

Before reading:

How many lines are in this poem?

How many stanzas are in this poem?

Circle the words at the end of each line.

Katie then reads us the poem (twice) using expression and volume dynamics. After her reading, she instructs us to answer the following sentence starters.

After reading:

I noticed that the lines of this poem break…

I noticed the author started a new stanza when…

We then share with our shoulder partners and then the whole class. Katie is a master teaching in the making. She brings us through a productive line of questions requiring us to notice, out loud, what words end lines, and what that means for the oral reading of the poem.

We next read ‘The Meet’ by David MacDonald. It only has one stanza and 19 lines. We discuss how the form of the poem (no breaks, short lines) mirrors the form (a poem about bursts of speed during a swim meet). We discuss intentionality, how the author does things on purpose for specific reasons.

Our last poem is ‘Afternoon Beach,’ a longer poem about, well, an afternoon at the beach. We circle any place where the author has changed the spacing. We choose one that we find especially interesting and write one sentence (just one!) about why I think the author put those words on the page like that. Why did the author form the lines in that way? We say the author uses spacing to mirror the content. A line about pushing is indented out. The author reins in the next line which simply reads, ‘pull me.’ Staggered words slowing the reader down and pulling them into a crisp dive into the water on a scorching summer day. The author writes “oceansky” instead of “ocean sky” to mirror the way the horizon and the water can bleed together into a hazy

Some of Our Final Observations:

-Lines end with important words

-Lines break to show a pause or where to take a breath

-Line breaks can add rhythm or pattern to a poem

-Stanza breaks show a change in the poem

-Stanza breaks can add drama or make words to stand out

-You can write in prose, then circle the words you want emphasized, then rewrite as poem

Katie then shows us a poem she’s written (free verse, of course, to match what the students are doing) that incorporates the same aspects of line and stanza breaks we’ve been discussing. What a pro! Her annotated example models how writers think. She makes her thinking public, explaining six specific choices she’s made. The message here is that we’re all writers. We’re all part of a larger community committed to writing, to the process of cracking meaning out of the aether. This “author talk” is essential.

So, we move into the good work. Katie has us break the same paragraph into lines and stanzas.

We discuss the similarities and differences in our individual break-ups. We all have various moments of “writer jealousy,” wringing our hands in envy at each fantastic turn of phrase and clever line break.

A killer lesson. Changing students into writers. Introducing them to the validity and power of their own experiences. Giving voice to the world of children that, no matter how hard adults try, is a place of endless meaning and importance.