Category: Reading

You Are In Here: How Infinite Jest Pretty Much Changed My Life

This month marks the twentieth anniversary of David Foster Wallace’s incendiary Infinite Jest. A book described by Spin magazine as “An acidic, free-styling, 1,088-page encyclopedia of hurt.” I want to take a moment to pen a brief essay describing how and why this book is so important to me.

Like most things intellectual in my life, my initial exposure to the book came by way of my father. My dad has always been a man of frightening erudition. Entering into the rarified atmosphere of his condo as an adolescent felt like stepping into a museum: muted colors, hefty tomes, and angular furniture. He is a man of strict routine and spatial consistency (a constellation of traits I share).

He decorated his dining room table with three dessicated pomegranates and whatever book he was reading. The only other items I ever witnessed on the massive wooden slab were whatever culinary accoutrements accompanied our delicious meals (my father is an outstanding cook, a predilection I have yet to pick up). Regardless of change in the outside world, I could always count on hopping into one of those reed-thatched chairs and being greeted by three lumpy pomegranates and a book. Nothing more, nothing less. At the time I wasn’t much of a reader, preferring instead the acidic rage of metal and industrial music. The books, which he swapped out without comment every week or so, rarely interested my adolescent self.

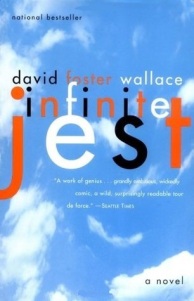

One afternoon in the 90s, however, a large book on the table caught my eye. The cover, an idyllic blue sky dotted with clouds, drew my attention immediately. Something about the color scheme of orange, blue, white, and black was aesthetically irresistible. And the size! The thing looked to be a solid three inches thick.

I took a chance and asked my dad what it was about. He told me it was complicated, that it messed with time and space. He said he wasn’t entirely sure what it was about, something I’d never heard him say before. Sensing the book was one of those tokens of adulthood far beyond my own puerile range, I was intrigued yet skeptical. Would I like it? I asked. My dad paused for a second. You’re not ready, he said. It wasn’t meant as an insult and I didn’t take it as one. I trusted his judgement and immediately forgot about it.

It would take ten years before I remembered that conversation. I found myself in a Barnes and Nobles on a date. Jazzed up on adrenaline and eager to impress, I dragged her into the critical theory section to show off a few of the books I’d recently read for my grad school classes. Then, out of nowhere, popped the memory of that conversation with my dad. I whipped out my cell phone and called him up on the spot.

‘Hey, Dad! Remember that time you had this big book on your table and I asked if I could read it and you said I wasn’t ready?’

‘…’

‘It was really colorful. It had clouds on the cover, I think. And it was big.’

‘Oh, yes. Infinite Jest by David Foster Wallace.’

‘Am I ready now?’

‘… Yes.’

That night I launched myself into the book. It was unlike anything I’d ever experienced before: hyper intelligent, hilarious, and incredibly incredibly sad. I loved the dizzying vocabulary. I kept a vocabulary journal next to my bed and wrote down words like ‘ascapartic,’ ‘homodontic,’ and ‘uremic.’ I struggled to make sense of the multiple plots and the many characters who popped in and out and spoke in radically different voices. I was so confused. And then sometime after the first 300 pages it started to click. Characters began to solidify and the multiple plots started to coalesce. The book asked a lot of me. Its complexity demanded rereads, scribbled down notes, and multiple bookmarks. But oh was it good.

The core of Infinite Jest deals with addiction, depression, and survival. How to hurt. How to survive. How to step outside yourself and resist the narcotizing pull of solipsism, technology, entertainment, and substances. It’s the book I needed to read at that time of my life. I was a full-blown alcoholic polishing off a 12-pack a night. Blackouts became the preferred vehicle for sleep. Days of being flayed alive by self-hatred seemed survivable when I could spend the nights submerged in the numbing slow-death of drink. Although most of me wanted to quit, I didn’t know how.

Infinite Jest, and by extension David Foster Wallace, showed me a way out. The book gave voice to the infantile hurt that propelled me into addiction. Although the entire novel contains too many quotes and lessons and take-aways to mention, the following blockquote has always been one of my favorites. In it, one of the two protagonists struggles to stay sober in the face of extreme pain and readily available narcotics.

He could do the dextral pain the same way: Abiding. No one single instant of it was unendurable. Here was a second right here: he endured it. What was undealable-with was the thought of all the instants all lined up and stretching ahead, glittering. And the projected future fear. . . . It’s too much to think about. To Abide there. But none of it’s as of now real. . . . He could just hunker down in the space between each heartbeat and make each heartbeat a wall and live in there. Not let his head look over. What’s unendurable is what his own head could make of it all. . . . But he could choose not to listen.

This notion that I could endure anything if I broke it down into individual seconds helped me quit alcohol for good. At first, the idea that I would never drink again was too painful for my brain. I couldn’t possibly conceive of a life, much less an entire week, without drinking. I figured out if I just kept putting my next drink off, if I continuously told myself I’d go to 7-11 in another minute, I could abstain. I hunkered down and repeated “just one more second” until it became “one more minute,” “one more hour,” and then “one more day.” Addiction draws much of its power from its simplicity. It doesn’t care about anything other than securing that next fix. By blinding myself and willingly engaging in self-deception I was able to escape.

Although I’m not saying I never would have gotten sober without Infinite Jest, it’s safe to say the book gave me the philosophical and emotional tools necessary to change the direction of my life.

Beyond helping me with addiction, Infinite Jest reminded me just how fun reading can be. David Foster Wallace’s books and interviews helped me understand myself and the world around me. I quickly became obsessed. I bought all his books, joined the David Foster Wallace listserv, travelled to Amherst to read his theses, bought Infinite Jest-inspired clothing, and pretty much talked to anyone in earshot about how amazing he was.

My David Foster Wallace book collection. Signed first editions, advanced uncorrected proofs, readers, etc.

While the book was also instrumental in my reading and writing life, I’ll save that for a later post. It’s the first answer whenever anyone asks one of those desert island ice-breakers so common in the ed/corporate world. It was my litmus test when searching for a mate. It ended up being the book that showed me just how powerful words and ideas can be.

If I Stuck a Camera into Your Brain, What Would I See? Responding to Literature

Introduction

In this series of lessons I attempt to apply Peter Elbow’s writing response techniques (previously mentioned in posts like this one) to help students respond to literature. Elbow’s response types require different modes of thinking; by combining them, my hope is that the final product helps students exercise a variety of aesthetic/cognitive muscles. The idea here is to train their attention to the creative world lurking beneath the material of the page. To try and guide each student’s perception to engage with an author’s words and ideas.

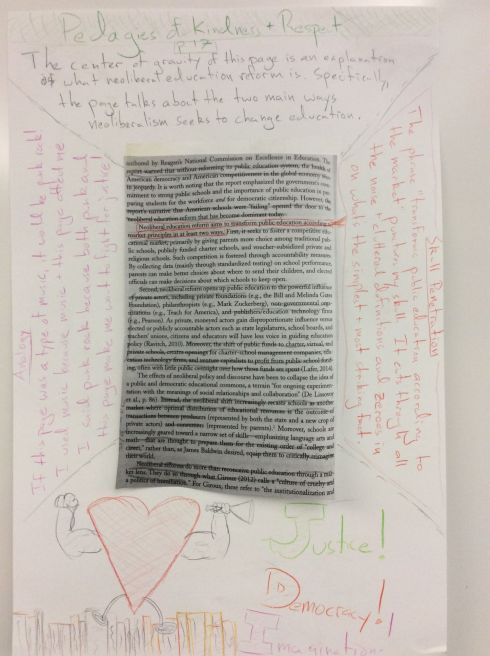

Below you’ll find a copy of my own response page. I chose to respond to Pedagogies of Kindness and Respect, a wonderful new volume of essays devoted to education and caring. Although my own students wouldn’t be able to access the text (I don’t know too many 7th graders interested in the ethics of neoliberalist ed reform), I didn’t want to phone it in. The more seriously I took the assignment, I figured, the more prepared I would be to help.

The Process

Students began this process by selecting a page from their independent novel. They spent time in class figuring out what it is they look for in a book. Students listed elements such as humor, action, character development, and interesting dialogue.

With this list front and center, students went off to read. I made sure to provide ample in-class time for reading. Every time students found a potential page to use they inserted a strip of paper as a placeholder and kept reading. After three consecutive days of in-class reading, each student had at least two options for choosing a response. Once students settled on a page, they shared it with me and I printed them out.

Students spent the next 2-3 days drafting their four response types. Again, although I’ve spoken about these response types before, here’s a short rundown.

1. Skull Penetrations: What word/phrase from the page penetrates your skull? Why? This is a good chance to work with students on summarizing (this is what the phrase is and means) and analysis (this is why it was so affecting).

2. Center of Gravity: What’s the main idea of the page? What idea or event seems to be at the center, pulling everything else towards it? What do a majority of the details lean towards?

3. Analogy: I love analogies. A lot. Students had to pick something to compare their page with. How is the page like a sport? What about an article of clothing or type of food? Students always struggle with analogies; and for good reason, they can get pretty abstract pretty quickly. Although they’re easy to scaffold on the spot (helping students list qualities of the page, then seeing what else has those qualities), analogies require a real mental leap of faith.

4. Mind Model: This is an illustration of what happens to a student while he or she reads the page. I tell them to imagine I’m sticking a camera into their brain while they read it. What would I see? The key here is differentiating between drawing the page vs. drawing your reaction to the page. This nuanced difference takes time to develop. I struggled with it myself.

Before students turned to their own page, we practiced each of the response types using a page from the fantastic Y.A. novel Yaqui Delgado Wants to Kick Your Ass. I found a good page, cleaned it up a little, and added a few parts to make sure it was rich enough for each response. By using a shared text and practicing each response one at a time, every student in the class heard twenty different skull penetrations, saw twenty different mind models, etc.

After that, students worked on their own page. I spoke with them individually and did my best to push their thinking. I also created slides such as the following to help students think through the response types.

The Results

Below are a handful of images I took of student work. I tried to capture a representative range of the abilities present in each of my classrooms.

The Rationale

Not every child takes immediately to the written word. Regardless of how exciting a book is, direct and sustained engagement with a text requires more than simply providing exciting books. I have many students who for various reasons struggle to sustain attention on even the most engaging of books.

I do think that sustained attention is something to be developed. Accessing words and images requires perception, cognition, and the ability to reciprocate with the page. To take what are essentially dead words, flecks of ink arranged in patterns on cheap recycled pulp, and pull them into ourselves. Smarter individuals (Rosenblatt comes to mind immediately, of course) have written much about reader-response theory, and I don’t want to unnecessarily muddy the waters. My point is that developing a relationship with a text is a give-and-take. I hope this lesson works towards that end.

Thanks for reading!