Category: School

Distance Learning Resource Round-Up for the 2020-2021 School Year

Hi! I teach English Language Arts to middle schoolers.

The idea of beginning the year 100% virtually makes me shit my pants from anxiety. In order to ease some of this distress, I spent the last few days compiling a list of everything I thought might be useful as we begin the 2020-2021 school year. While doing so didn’t help my nerves, I’m hoping it might be helpful to you!

If you want, you can also access the original Google Doc here or simply scroll down below.

See a link that looks good? RIGHT CLICK ON IT AND OPEN IT IN A NEW TAB. Otherwise it might not open in WordPress.

I’m sure I’ll keep tinkering with it over the next few weeks. ENJOY!

A Million Different Directions

One by one, tiny pixelated faces began populating the grid on my monitor.

“HEY! LET’S SEE WHO’S HERE! WOWOW! I MISS Y’ALL SO MUCH!” I shove my face towards the camera, checking out my pores and zooming in on my flared nostrils for comic relief. A few students giggle, but most of them seem pretty nervous. Maybe I’m just projecting my own anxiety on them. Probably a combination of both.

For the next thirty minutes we engage in our first ever virtual check-in. The kids who try to dominate class discussion try to dominate the virtual space as well, gabbing effortlessly about the latest news they’ve heard. Some of the less extroverted kids appear only as half moons at the bottom of their video window, the top of their heads stuck like hesitant suns unsure whether or not to rise in the morning. Dogs and babies make appearances. Every now and then a parent walks in and waves. There’s no agenda or clear instructional purpose.

I held this virtual check-in because some parents and kids asked me to. And because I know other teachers are doing it. I know other teachers are doing it because social media is awash in stories, slices of life, and think pieces about the intersections of the Coronavirus and public education.

“HERO TEACHER READS STORIES OUT LOUD TO STUDENTS EVERY NIGHT”

“TEN WAYS TO USE ZOOM TO TAKE YOUR VIRTUAL TEACHING TO THE NEXT LEVEL”

“TEN WAYS USING ZOOM VIOLATES YOUR STUDENTS’ PRIVACY”

Some posts make me roll my eyes, and others make me jealous inspire me to do things like hold the virtual check-in described above. Then there are the posts that hollow me out. The statistics about the percentages of children who rely on school lunch for food. About inequity in instructional practices. About the connections between quarantines and domestic abuse.

I know I’m not alone in my panic. Every morning my inbox is full with frantic questions from students and their families. When will you begin virtual teaching? Can you be virtual during the same hours as the school day? When will you be sending out a detailed list of instructional activities and due dates? Why aren’t you grading anything? Why are you grading anything? How can I make sure my child is ready for 8th grade/high school/college/life?

I have no idea; I’ve never been here before. None of us have. I don’t fault any families for trying to do what they think is best for their child. In the face of so many needs, I just don’t know what to do.

There is a paralyzing amount of information to take in, much less sift through critically and responsibly. What is my charge? How can I best help students right now? And what if what’s best for students isn’t necessarily what’s best for me and my family?

My family, like many, has been fractured by this. My wife must remain tethered to her work computer because her company expects their employees to be online at all times. (So much so that they actually track when someone is online and when they’re not. This is apparently somewhat common among white collar jobs. As a teacher, this combination of surveillance and technocratic accountability gives me the heebie jeebies.)

This means I’m entertaining my 21 month old daughter. The notion that I could hold some sort of virtual class, concoct meaningful lessons that are developmentally appropriate and accomplishable without teacher intervention during this time is ridiculous. Toddlers are anti-routine. The Coronavirus is anti-routine.

I’m incredibly fortunate to have my mom and her partner close by. They have generously agreed to watch Joelle for a few hours during the day. During those precious hours I rush through my daily teacher upkeep (so many emails!), complete my chores, maybe try to fit in some exercise, and do whatever other random things pop up. My ADHD adds another layer of chaos to the situation. I depend on those hours to maintain some sort of status quo.

Right now, my status quo is NOT healthy. It is heavy. It is tempered by the fact that my students and I are all stuck at home. It is bloodshot from the trauma. The statistics. The daily news of a world on fire. Elected officials bartering human life for stock profits. Communities reeling from waves of loss. Everyone being pulled in a million different directions at once.

Against and within this backdrop I wrack my brain for some direction that feels ethical, moral, and just. Right now it’s the best I can do to think small. Reduce the size of my world to something manageable. I can be gentle with myself as I steal away from the country’s obsessions with standards, scores, and scales. Hold myself and those I love close, pick a direction, and move. One foot in front of the other.

Photo by Evan Dennis on Unsplash

What Am I Doing? Coronavirus and the Teaching Unknown

We are in a global pandemic and everything has changed. Cortisol has flood my synapses. My neck, shoulders, and back feel like they’ve been fused together in a painful patchwork of rigor mortis. Some of this anxiety isn’t new; I’m always on edge. It’s in my guts.

That’s one of the many things I love about teaching. It harnesses and channels my anxiety. It shapes my nervous energy into a recognizable form that I’m intimately familiar with. It powers my lesson planning, classroom management, and entire teacher persona. It pushes me past the torpor that begins setting in anytime I’m directionless.

I’ve had a lot of time to feel directionless this week. The traditional boundaries that I’ve hewn to over the last decade have dissolved. My anxiety has nowhere to go. And in the closed network that is my neurological system, anxiety has to go SOMEWHERE. Otherwise it’s just a corrosive lake eating away at my insides.

Like many others, I hate being trapped in the gray, in those indeterminate spaces where options and vectors spin out. This is why I get extra antsy on snow days. As soon as it starts snowing, I become consumed with figuring out whether or not I’ll have to go into work the next day. It’s not the job that I hate (I LOVE TEACHING!), it’s the unknowing. Snow day anxiety is nothing compared to this.

Because I know what to do with a snow day. I play with my daughter. Watch movies. Bounce around the house stuffing my face with the heavenly cookies my wife bakes whenever inclimate weather strikes.

But this isn’t a snow day. It’s an unprecedented global pandemic that has upended the social and professional fabric of my life and the lives of my students.

Last Friday we were instructed to pack up our stuff and not come back until the middle of April. Four weeks. The guidelines for teachers in my district are anemic at best. We can post work, but it has to be review. Nothing new. And nothing can be graded. That’s it. These guidelines make sense, and I take no umbrage with them. I mean, what else am I supposed to be doing?

Well, based on the posts clogging my various teacher social media feeds, I should be downloading Zoom, holding video conferences with students, designing passion projects, etc. These things all sound great, but I’m not trained to do any of them. Distance learning is a legitimate subcategory of pedagogy with its own thought leaders, philosophical debates, and learning curve.

You don’t just start “doing” distance learning the same way you don’t just start teaching. Any teaching is serious, and anything serious requires intentional study and practice.

I’ve dipped my toes in and put some stuff online for my students. They have an online Coronavirus Notebook to help them keep track of their experiences throughout this historical moment. I give them daily focus questions and prompts. Insert a video time capsule where you record yourself talking about everything you’re eating, drinking, watching, feeling, and doing. Use a Creative Commons website to find an image that symbolizes your week and write about it. Etc.

So is this all I’m supposed to be doing for the next three weeks? Let’s say that it is. That plugs up one stream of anxiety while opening up another. What am I supposed to do when I get back from these four weeks? Should it be new? Should it pick up where we left off with some minor modifications? What role should the Coronavirus play? How does my moral and professional duty as a teacher intersect with an unprecedented public health crisis?

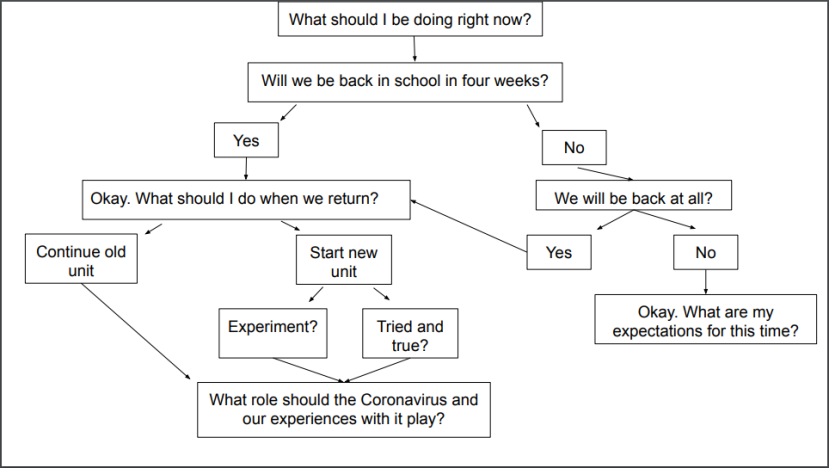

I created a flowchart to capture the manic sequence that’s hamster-wheeling in my brain. Here it is.

It’s an endless loop. A recursive cycle that folds into itself the the more I try to pin it down. The second I stumble upon a fruitful avenue (maybe I could do a unit on X!), my anxiety barges in like a toddler, picking everything up and depositing it somewhere else. While screaming.

I can’t really think of a conclusion for this post, just like I can’t come to a conclusion about what’s going to happen in the coming days and weeks. The key for me is to avoid the analysis/paralysis that often results from trying to think about too many things from too many angles at once. So I’m going to stand up right now and make a sandwich.

Four Weeks

NO SCHOOL FOR A MONTH! NO SCHOOL FOR A MONTH! NO SCHOOL FOR A MONTH! MR. ANDERSON, WHAT’S WRONG?

The muscles holding my face together must have gone slack as my brain chomped its way through a variety of unprecedented scenarios. I swiped down on my phone for what must have been the five hundredth time that day to verify that this was indeed happening.

It was.

The energy inside the school had congealed this week, and now it was heading towards the surface like a fresh zit on one of my student’s foreheads. By Friday morning, the day of the announcement, we were frothing at the mouth for some sort of information. In the absence of official channels, everyone became an insider. Group chats lit up as teachers speculated about what would happen next. Kids swore up and down that their mom worked with someone who got their hair done at the same salon as the superintendent. Everything began with some form of “You didn’t hear it from me” or “It’s not official yet, but…” In truth, no one knew anything.

My first two periods that morning were easy. No one knew anything, so students were content (enough) to do their independent reading for our new unit. By the time lunch hit the day was beginning to feel almost normal. The weekend was unfolding before me like it always did, with its combination of chores, family time, and enjoyable but stressful lesson planning.

Five minutes before lunch ended the news landed. It was official: four weeks “off.” Now, students aren’t supposed to have their phones on them during the day, but they all do. I knew that if I had just gotten the Tweet, so had everyone else. Before my mind could begin processing what was about to happen, kids started pouring into the room.

I commanded them to sit down and start reading, but my heart wasn’t in it and they knew it. Some humored me and opened up their books. Some even started reading. I went back and forth about what to do. Part of me wanted to enforce the day’s silent reading lesson plan. But another part of me wanted to be realistic. If I was a 7th grader in this exact situation, what would I want? What would I need? Getting middle schoolers to sit still is a challenge in the best of times. What about during a global pandemic, facing an unprecedented school shutdown?

I made up my mind: we were going outside. I didn’t have a plan. I didn’t have any games or sports equipment. We didn’t even have a field for them to run around in, just a long stretch of manilla concrete dotted with uncomfortable benches at puzzlingly random intervals. But it didn’t matter. The kids needed to move and I needed to be still. What the hell had just happened?

I leaned against some metal fencing and squinted through the early spring sun. Groups of boys raced up and down the concrete, hooting and hollering about who was the fastest. Squads of girls gathered around cell phones, recording TikTok videos of themselves dancing and lip synching. It was surreal.

After touching base with the handful of kids who were hanging out by themselves, I let my thoughts spin. The instructional sequence I had spent the last two weeks drafting, iterating, and refining was now moot. The seating charts and group activities and anchor charts I had dutifully created were now useless. I wasn’t upset, just lost.

At 2:24 students raced out of the building and into the waiting mouths of school busses. Some students hung around after the final bell, their eyes communicating what their mouths wouldn’t: was everything going to be okay? What was about to happen? I offered what reassurances I could and packed up my own things. I floated out of the building. Nothing felt real. Students, cars, trees, everything around me looked two dimensional. I felt untethered.

The following days didn’t do much to ease my confusion. Every thumb swipe of my phone seems to yield new developments. New vectors for what the next month might possibly bring. For now, I’m clinging onto those four weeks. 28 days. 28 stepping stones guiding me through this miasma of unknowing. In time, the students and I will return to the classroom. We will again be sheltered by the predictable rhythms of assignments and lunch periods and hallway transitions. Until then, I float.

Sometimes Parent Teacher Conferences Hurt

I leave today’s parent teacher conferences feeling both rejuvenated and queasy. On one hand, there’s nothing like sitting down with families to discuss their children’s education. I love how these parent teacher conferences make me feel. They make me proud to be a teacher. My spirit is fed by the immense responsibility of guiding children through their formative middle years.

In these meetings talk of goals and life trajectories encircles us. We revel in the shared purpose of enriching our communities and our worlds. The best parent teacher conferences reveal and strengthen the profound connections we have with each other. The resulting sense of shared responsibility and accountability cannot be replicated by standardized test or top-down initiative.

When we’re all on the same side, it feels like we are the village.

But sometimes parent teacher conferences can hurt. In these moments I feel like a spectator, an unwilling voyeur forced to watch a parent spirit murder their young. Words can cut. They can accrete over time, slowly rotting away a child’s identity and confidence until there’s nothing left. I’ve watched parents bully their kids into submission. I’ve watched children shrink before my very eyes. Watched them tunnel into themselves until they become nothing more than a ventriloquist’s dummy mindlessly parroting back whatever they’re told.

When this happens, I have to change tactics. I try to highlight the child’s strengths, relate an amusing anecdote, crack jokes, do anything to short circuit or at least redirect the crumpling gaze of a parent who has lost themselves. Even when I’m able to successfully defuse a situation, I know the relief is temporary. I’m only bearing witness to a sliver of whatever is going on. And there is always something going on.

The possibilities are numerous and formidable: toxic masculinity, inequity, substance abuse, a disastrous lack of social services. Generational patterns of abuse and neglect that leave so many of us broken and gasping for air. During such conferences I become acutely aware of how small I am. How small we all are when the profound love of family and community festers and turns against us.

As I leave the building for the weekend, I struggle to process what I’ve just experienced. The horrors I’ve witnessed leaking out of some children rests uneasily beside the protective aura of unconditional love emanating from other children. It is a juxtaposition without resolution.

The events detailed in this post draw from my multiple experiences at multiple schools across multiple years.

Point Sheets Make Me Want to Barf

“HERE” Martin thrust a crumpled sheet of paper at me. Before my mind could figure out what I was supposed to do with this botched piece of origami, I noticed the telltale Google Docs table outline that could mean only one thing: a point sheet.

For the three folks reading this who aren’t teachers, a point sheet is a common method used by schools to try and shape a student’s behavior. Teachers and student decide on a couple of academic, behavioral, and social goals to focus on and track throughout the day. The goals are usually pretty standard: completes all classwork, comes to class prepared, etc. The kid carries around the point sheet with them from class to class. At the end of each class, the teacher is supposed to mark off on the sheet whether or not the student met the goals. Point sheets draw from crude behaviorist notions of behavior modification.

I smoothed out the paper on an empty desk, clicked my pen, grabbed my laser pointer, and read. The instructions were clear. Each of Martin’s teachers were to put a “1” or a “0” next to each goal. A 1 meant Martin needed fewer than two reminders, whereas a zero meant he needed more than two redirections.

Martin’s goals were as follows:

- Treat teachers and students with respect.

- Complete all classwork.

Regardless of the relative simplicity of the point sheet’s instructions, Martin’s sheet was covered with a variety of symbols. Some teachers went with a check/check minus/check plus system; some teachers used checks and X’s, and other teachers filed the margins with last minute explanations and commentary.

My brain poured through its videotape of the class period that had just ended. Doing this with the particular brand of objective fidelity required by the point sheet would be challenging under any circumstances. It was especially vexing in the unadulterated chaos that is the interstice between two class periods.

Martin hovered next to me, hopping from his left foot to his right as he waited and watched. “I did good today, right? Right, Mr. Anderson? I did good today. My mom really wants me to do good today. I’ll get my phone taken away by my dad if I get any bad marks. But I did good today, right? Better, for sure. Right?”

I mean, Martin DID do well today. But here’s the thing: it took an Herculean amount of effort to get him there. I parked myself next to him whenever I could. That way anytime he ran his mouth (which he was forever never not doing), I could steer his monologic flow back towards the assignment. He worked on his handout, but he didn’t complete it. So what does that mean for his point sheet? If I use a literal reading of the goal, then I would have no choice but to give him a zero. But what if I overplanned the lesson? What if the instructional sequence I designed for the day was confusing? Maybe Martin found neither value nor relevance in my lesson. In that case, am I just asking him to do what I tell him to just because? Do I want to be cultivating students who value compliance?

His second goal, being respectful, was equally challenging to capture in a yes/no binary. Throughout the class period Martin required multiple redirections and nonverbal cues to stay on task. He interrupted me, made fart sounds at a student, and shouted non-sequiturs during the warm-up. He was currently flashing the laser pointer he had deftly yoinked from my hand around the room, narrowly missing several students’ corneas.

I spend more energy on him than most of the other students in his class combined. If class were a pinball machine, I’d be the rubber bumpers and Martin would be the pinball. He keeps plummeting towards the bottom and I keep catching him and boosting him back up. The game is played at a feverish pace. There’s no end. I just try to avoid running out of quarters until the timer runs out.

But was he disrespectful? Were his actions throughout the 42 minute period indicative of someone who is unkind and malicious? Martin is a neurodiverse student who struggles to fit into the complex mazes of overly punitive policies that form the core of public schooling. I’m not familiar with his home life, but I’d bet my job on some form of trauma in his family history. I’m not making excuses, just trying to understand exactly what is going on with this intelligent, quick witted, and observant adolescent in front of me.

In many ways, the point sheet can be seen as a synecdoche for school. Despite whatever’s going on at home, despite the energy I’ve spent cultivating a relationship with Martin, regardless of the staggering amount of labor I’ve expended trying my best to create rigorous, engaging, and culturally relevant lessons, at the end of the day, it all comes down to a single mark. There is no room for nuance or complexity. When the needs are so great and the resources are so few, everything is flattened and reduced.

Exhausted, I sign off on his point sheet, grab the laser pointer, and tell him to go to his next class. He looks at my notations and shouts “LET’S GO!” before plunging head first into the throng of students milling around outside my room, knocking down a sixth grader and sending assorted books and pencils flying in the process.

Later that afternoon I pack up my stuff and head out of my room ready to go home when something catches my eye: Martin’s point sheet crumpled up and ground into the carpet. It must have fallen out when he careened into that sixth grader. I shove it into my pocket, telling myself I’ll check in with him first thing tomorrow morning. But I don’t. I forget. Thank goodness Martin doesn’t get to fill out a point sheet for me.

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

-For the sake of anonymity, this post draws inspiration from a variety of students. “Martin” is not a stand-in for any particular student but instead a composite of many of the wonderful kids I’ve been fortunate to work with.

Be Curious, Not Furious: On Student Behavior

James* bursts into my classroom late, singing at the top of his lungs. “WHAT ARE WE DOING?” he shouts to no one in particular. I point to the SMART board where the warm-up instructions are posted. He stomps to the middle of the room, stops singing, and starts dancing. “WHAT ARE WE DOING?” he shouts again while gyrating. And again I catch his eyes, point to the warm-up instructions (read independently for ten minutes), and pantomime opening up a book. “WHAT DID WE DO IN SCIENCE CLASS?” James yells out to no one in particular. Most of the class continues to read. I bring over 3-4 books I think James might like. “I HATE READING” he shouts at me. I continue to breathe deeply and slowly, paying special attention to keep the muscles in my shoulders, face, and hands relaxed. James picks up one of the books and then puts it back down.

“HEY WHAT ARE WE DOING IN SCIENCE CLASS?”

This moment has played out in some form or another since September. Sometimes James has in-school suspension. I’d be lying if I didn’t admit that I breathe a little easier on those days. Without James I can spread my energy around to other kids in the class. Kelly for instance has awe inspiring impulse control issues. With James gone I can park myself next to Kelly. It’s the only way I’ve found to decrease her ceaseless flow of colorful commentary.

I’ve met with James, his parents, other teachers, and the counselor in a variety of configurations. His grades are in the tank and he floats in and out of various detentions and suspensions. It’s obvious that James needs a lot of support. The meetings always end the same. We tell James to go to homework club. We tell his parents James can get make-up work from his teachers and have extra time to complete it. But a couple of weeks later everyone is back where they started.

I have a lot of kids who struggle like this. They might not be as disruptive to the classroom, but they’re floundering the same. These are the kids teachers and schools often pathologize as “lazy” or “undisciplined.” Schools and teachers are much better equipped to deal with a “lazy” student than they are a traumatized one. Kids who aren’t doing their work can go to homework clubs. They can get help before, during, or after school. They can get make-up work from teachers. Their progress can then be monitored by parents and counselors via online gradebooks.

In a way, the availability of these resources can make it harder to respond to a child with compassion. You can have a million different hammers, but you’re still out of luck if you have to do anything other than push in a nail. And with students like James and Kelly, it’s obvious there’s more there than a kid simply choosing to ignore their studies.

A Twitter exchange between Shana V. White and Daniel Torres-Rangel sums this up:

Social Psychologist Devon Price recommends we respond to a person’s behavior with curiosity instead of judgement. I know how hard this can be. We’ve explained the directions, had a student repeat them, projected them on the wall, and yet some students remain absolutely clueless about what they’re supposed to be doing. The meritocracy that permeates our air often speaks through us. If only these kids would try harder. Concentrate. Behave. Follow directions. The problem is that these demands might outpace the student’s ability to self-regulate.

Executive functioning, the umbrella term for cognitive mechanisms related to self-regulation, can take a big hit when someone experiences trauma. And we know from various studies that a large percentage of children experience some sort of trauma. Trauma can keep the body’s nervous system in a perpetual state of fight or flight. The effects of constantly elevated stress hormones can lead to memory and attention problems.

So how can we reorient ourselves, our pedagogies, and our schools to better help students who have experienced trauma? Alex Shevrin Venet suggests starting by sweating the small stuff. Build our capacity to live in the moment and offer individual therapeutic moments to our students. Express kindness and unalloyed compassion. Look beyond the behavior to try and figure out what’s really going on.

There is no quick fix. Schools are filled with hurt and traumatized children. And so many of us teachers were those children. We can refuse to take part in a culture of academic shaming and begin to construct communities of healing that understand and honor the connections between mind and body. Get curious, not furious.

* James and any other student mentioned in this post are not real kids, but a composite of multiple students I’ve had at multiple schools across multiple years. This is to preserve anonymity while keeping the spirit of the events true.

Asserting Basic Dignity in the Classroom

Last week was Black Lives Matter at School week. All across the country, teachers delivered instruction based on the movement. On Friday I talked with kids about affirming queer and trans Black lives, two of the movement’s 13 guiding principles. While I’d spoken about trans and queer lives before, the subject matter was always secondary to whatever content area skill we were focusing on. This lesson put the subject front and center.

We watched a short video of people talking about their experiences being both Black and queer. We read the horrific statistics behind transphobic and anti-Black bullying and made connections to what we experienced in our own school.

In every class period a handful of students explained that their religion and/or home cultures looked down on being gay, trans, etc. I told them emphatically that while that’s their business, there was nothing wrong with being gay, trans, etc. They made faces, protested, and told me I was wrong. I repeated myself and reminded them that our classroom was no place for any hate, prejudice, or bigotry. I tried to push our conversation away from individuals and towards the social structures that reinforced certain beliefs, but it was tough.

I was pulled aside a few days later to have a conversation about what I had said in class that day. Specifically that I needed to be more careful about letting my own beliefs influence the things I said and the ways I reacted to students. The conversation wasn’t threatening, but it wasn’t ambiguous, either.

I was making value statements about what some students heard, felt, thought, and said. I was explicitly stating that some of the things my students heard at home, in their churches, and in their communities had no place in our classroom. But if basic dignity was truly axiomatic, I wouldn’t need to assert these ideas. I wouldn’t receive push back against absolute bare-minimum messages of equality. And I wouldn’t have felt a minor shudder of cognitive discomfort when I said it.

The conversation reminded me just how insidious and pervasive white supremacy and heteronormativity is. There is nothing revolutionary about asserting someone’s basic dignity. Yet doing so was enough to alert the systems that continuously reinforce and reinscribe ideologies of discrimination and hate.

This is why it’s essential to assert and proclaim that Black, queer, and or/trans lives matter. To speak these truths into existence bluntly and without equivocation. And for teachers like me to use our privilege to break white male solidarity. Lesson by lesson we can work with students to carve out the spaces that everyone deserves.

Do You Enjoy This Class? Using Anonymous Surveys for Feedback

“This classroom is not a place where I’m able to learn because of the noise levels.”

“A group of students make it hard to work because of giggling and talking.”

“I do not feel respected by my classmates because of how some people act.”

These statements greeted my sixth period students as they entered the room two weeks ago. After everyone was seated, I asked them to reflect on what they saw. Did these statements accurately reflect what was going on in the room? After a brief discussion, I told students that I would make sure that they always knew what the expectation was. If an activity called for them to be silent, we would take ten seconds to practice what that looked like and sounded like. Students who struggled to meet the expectations would meet with me to talk through strategies and work on self-awareness. Not as a punishment, but as a chance to figure out what’s going on and how to work towards improvement.

The talk (and a couple of reminders since then) has led to a drastic improvement in the classroom environment. And it’s all thanks to the feedback of three anonymous students.

As teachers we’re inundated with feedback. Most of it comes through bureaucratic channels such as checklists, official forms, Likert scales, missives, spreadsheets, and percentages. This sort of feedback can be hit or miss. It’s often tied to faceless initiatives and whatever mandate is big in the edu-sphere at the moment. The feedback that matters most, the kind at the top of this post, can be the hardest to find. What do my students think about what’s going on in our class? Does my instructional style work for them? This type of feedback is built on trust and reciprocity between teacher and student.

There’s different ways to collect this kind of data, and each method provides a slightly different take. Meeting with a core group of students over a period of time, a la Chris Emdin’s cogenerative dialogues, helps you tap into how students experience your class on a day to day basis. What lessons worked? What discussions fell flat? Writing back and forth with students and their families in a notebook can provide a comprehensive portrait of how everyone is doing inside and outside of the room. Unfortunately it requires a dizzying amount of labor to pull off on a consistent basis. Luckily there will always be some kids who will just tell you when the lesson sucked. Like most teachers I rely on a combination of these methods.

I also like to do a simple “State of the Class” survey. I prefer to use an anonymous Google Form. Here’s a past example if you’re curious. It gives me a snapshot of how kids feel about me, my instruction, and our class. Some of the questions have to do with classroom environment (Do you enjoy English class? Is English class a place where you can focus on learning?) while others focus on instruction (Which of the following activities helped you improve as a writer?) My favorite answers come from the open response questions about how Mr. Anderson can improve. The answers mirror the period. I must admit, I put a couple more questions about classroom environment on my last survey because of sixth period specifically. In this case the feedback confirmed my own perceptions.

Going through the survey responses, I often get the feeling that I’m working too hard. That the time I spend massaging fonts and presentation slide syntax probably isn’t worth it. Do I want every unit to be a panoply of epiphanic activities and brilliantly sequenced lessons? Of course! But for a lot of kids, it’s just class. And that’s okay. I’m not going to lie and act like I don’t go home and agonize over every survey that reveals a kid doesn’t absolutely love my class. But it’s a necessary reminder. I also enjoy sharing the data with students. That way if anyone groans about reading, I can remind them that 73% of students asked for more independent reading time.

Whether you give a survey, write back and forth, or meet with kids during lunch or after school, the feedback you receive is invaluable. Do kids like your class? Do they feel respected? Do they feel like they’re learning? This sort of feedback cuts through the noise and hierarchies and gets at some of the most important questions to any teacher.

Try Writing with Your Students

Teaching students how to write is really hard. Students need direct instruction, engaging “real world” models, time to write and revise, an audience they care about, and assignments that appeal to them. Even on the best of days when we’ve somehow managed to tick off all of these boxes, we still have to wrangle with the morass of hormones and developmentally appropriate inattention that is the hallmark of a middle schooler.

Like most teachers, I’m constantly swapping out new (and old) writing pedagogies in search of anything that will get my students excited about their writing. But no matter what instructional methods I’m trying out, one tool remains consistent: writing alongside my students. I don’t mean cobbling something together to offer as a finished product to emulate, but actually getting down into the trenches sweating it out word for word with them on every assignment.

This does a few things. It helps me treat writing seriously and unseriously. Both perspectives are necessary for a writer. It’s also a quick way to find out whether or not an assignment sucks. Working on a piece of writing alongside my students helps me see the nuts and bolts of the assignment. The more I do it, the better I become at predicting where the sticking points will be. Which areas I can gloss over and which skills will require a deep dive. It gives me a chance to demystify the writing process and show students just show much work goes into crafting something even semi-coherent.

When I write with my students, I send the message that what we’re doing in the classroom is worthy of serious time and effort. And that we’re in it together. The feedback goes both ways.

The call for teachers to write with their students is nothing new. A debate about the efficacy of writing alongside students raged across the pages of NCTE’s English Journal in the nineties when high school teacher Karen Jost argued that the time it takes for teachers to write is better spent conferring with students. Teachers already have too much to do, she explained. The demand that teachers of writing now themselves should be writing smacked as yet another example of teachers being told what to do by supposed thought leaders who hadn’t stepped foot in an average classroom in years.

In many ways Jost wasn’t wrong. There is no time. It’s impossible for me to do everything I’m supposed to do. Every day is a series of cost/benefit decisions. I get one 45 minute planning period unmolested by meetings a day. Do I spend it in an IEP meeting that will surely go into my lunch break? Or do I use that time to provide written feedback on student writing? But if I do either of those, I won’t be able to finally meet with that student who has been writing about how bad his depression has gotten. I also need to check in with the counselor about a student’s math placement and think ahead to tomorrow’s lesson. Few of my options deal directly with classroom instruction and the Herculean task of growing readers and writers. So I understand why asking teachers to begin writing with their students seems like just another task.

But that the decision to write alongside our students isn’t a binary choice. It’s more of a stance we take towards curriculum, instruction, and our place inbetween. A teacher as writer stance connects us with the art and science of writing in a way that no rubric or exemplar ever could. It’s the best way to learn that a piece of writing’s center of gravity changes multiple times throughout the writing process. Or that no matter how hard an author wrestles with a piece, sometimes it just doesn’t work out.

To get started, consider one place you can write with your students. A brainstorming session for an upcoming essay or poem, for instance. The good thing about students not being used to their teachers writing is that they won’t call you out if you don’t follow through on it.

Writing alongside your students will fundamentally alter your relationship with what you teach, how you teach it, and how you relate to students. And as this relationship begins to shift, so will your relationship to the writing instruction that’s going on around you. You will (re)connect with the transformative potential of literacy and the power of words to bind us together. It’s a way to come home to a profession that seems so bent on throwing up hurdles between what we do and why we do it.