Category: Teaching

Distance Learning Resource Round-Up for the 2020-2021 School Year

Hi! I teach English Language Arts to middle schoolers.

The idea of beginning the year 100% virtually makes me shit my pants from anxiety. In order to ease some of this distress, I spent the last few days compiling a list of everything I thought might be useful as we begin the 2020-2021 school year. While doing so didn’t help my nerves, I’m hoping it might be helpful to you!

If you want, you can also access the original Google Doc here or simply scroll down below.

See a link that looks good? RIGHT CLICK ON IT AND OPEN IT IN A NEW TAB. Otherwise it might not open in WordPress.

I’m sure I’ll keep tinkering with it over the next few weeks. ENJOY!

Speaking Your Truth Through Slam Poetry: A Unit Overview

“We’re doing poetry? I haaaaaaate poetry! It’s SO boring, Mr. Anderson!”

One of the easiest ways to make a room full of middle schoolers groan is to say the word “poetry.” I don’t blame them. The thought of analyzing the theme of “Hope is the Thing with Feathers” or any of the other nature themed poems that regularly pop up on standardized tests makes my eyes slide back inside my head.

A few years ago I began teaching a unit on slam poetry. Students responded immediately to slam poetry’s relevance, topics, and overall style. Slam poetry feels vibrant and current. And thanks to the internet, teachers now have access to cutting edge slam poetry written by people that look and sound like their adolescent students. I’ve taught this unit three years in a row, and it never fails to produce some of my students’ strongest writing of the year.

What follows is my basic blueprint for my annual slam poetry unit. This unit combines “just right” mentor texts with rock solid instructional activities. Because it requires students to be vulnerable, I typically save the unit for the back half of the school year. That way I’ve had time to build and sustain a sense of classroom community with students. Without vulnerability, slam poetry is nothing.

Unit Title: Speaking Your Truth through Slam Poetry

Time Length: Five weeks of 42 minute class periods

Final Product: Students will write, revise, and submit an original slam poem. While students do not have to present, they are encouraged.

Standards: These are from Virginia. I’m sure most states/Common Core have something similar.

- describe the impact of word choice, imagery, and literary devices on different poems (7.5d)

- analyze the themes of various poems (7.5a)

- write, revise, and edit original poetry that that incorporates word choice, imagery, and literary devices (7.7d, g, j)

Mentor Texts: Ten years of teaching English Language Arts has taught me that providing students with engaging, developmentally appropriate, and culturally responsive mentor texts from the “real world” is the most essential component of a successful unit. To that end, I’ve collected every slam poem I’ve ever used into a mentor text packet for you to make a copy of. Every poem in this mentor text packet has a corresponding YouTube video of the poet delivering (or ‘slamming’) their poem.

Content Warning: If you plan on using these poems, make sure you read through them first. For some of the poems I give a content warning and provide students with a chance to sneak out first. The poems here deal with topics such as: anxiety, depression, grief, ADHD, race, gender, substance abuse, technology, and religion.

Basic Instructional Sequence: The basic instructional sequence for this unit is adapted from the mentor text model described by Katie Wood Ray in Study Driven. Students begin by “immersing” themselves in slam poems. They listen, discuss, read, and write. The next step asks students to “write under the influence” of the mentor texts. Finally, students use specific texts and techniques to revise and deliver their poems.

Immersion Phase: Expose to students to the mentor texts. Get them reading, writing, and talking about them.

- Introduce the genre with a high interest slam poem (You can never go wrong with Touchscreen). Help students identify the difference between first and second draft reading. The former helps students access the content (the WHAT of the poem) while the latter gives students a way to analyze the craft moves made by the poet (the HOW of the poem).

- Introduce one poem a day to students. Watch them multiple times. Read them multiple times. Give students room to respond to the poems in a way that suits them. This is where I introduce “punctuation annotations.” Students read through the poems and mark up the lines with hearts, exclamation marks, question marks, etc. What surprises them? What lines can they identify with? Etc.

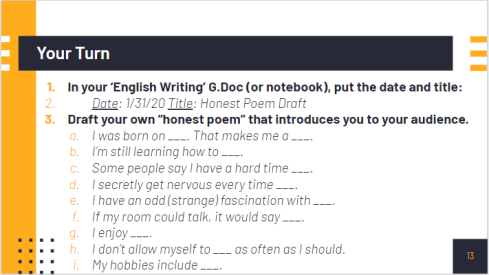

- Then, have students use the basic framework of the day’s poem to generate their own version. The goal here is to give students their own bank of writing to draw from when it comes time to commit to a draft. I always give students two options. They can just “go for it” and write something with the mentor poem on top of their brain. Or they can use a “poem frame,” a more sophisticated fill-in-the-blanks. This requires the teacher to use a poem with an easily identifiable and copyable format. Below is one of the slides I used from the excellent Honest Poem by Rudy Francisco. The bullet points on the slide come from lines in the poem that I adapted.

- Students end this phase filling out a simple “What is slam poetry?” handout. It has four basic questions about what slam poetry is, how it’s different from more traditional forms of poetry, and what they can write about for their own poems. Students have immersed themselves in slam poetry for about a week at this point, so there isn’t much scaffolding or direct instruction that happens here.

Writing under the influence: Students use the mentor texts as guides to help them write their own poems.

- The goal of this short phase is for students to complete their “down draft.” To just get something “down” on the paper. We’ll fix it “up” in the next phase.

- Students are encouraged to “talk back” to any ideas or stereotypes others might have about them. I typically introduce this idea by asking students to tell me what they assume about teachers. That we have no lives. That we live at school. That we hate kids. You can spend as much/little time with this as you want.

- Students can use any of their poem quick writes from the previous classes.

- Students can practice “lifting a line,” a simple technique where students pick a favorite line from a poem and use that to either begin or end their own original poem.

- I try to help them focus on quantity instead of quality at this stage. I shout “JUST WRITE!” a lot during this time.

Using Mentor Texts to Revise and Polish: This is where the real work comes in! Now that most students have a workable draft, it’s time to begin the labor intensive process of revision.

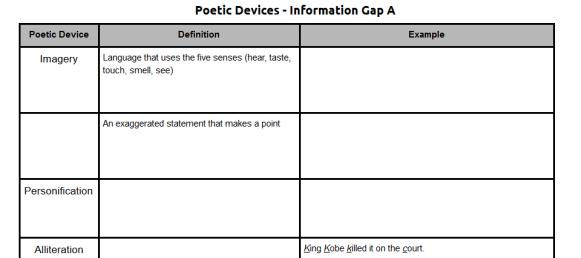

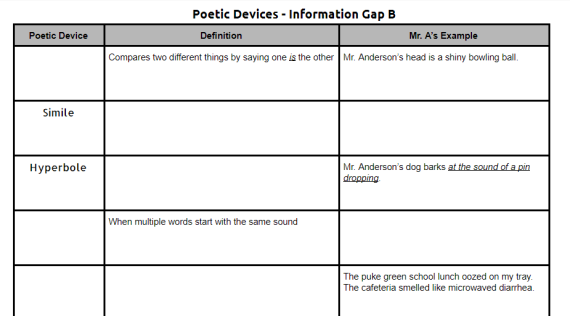

- To make sure we’re all on the same page with language, we begin this step by tabling our drafts and diving into language with an “information gap” activity. Students partner up, sit back to back, and try to fill in the blank spaces on their handouts. While each student has the same information on their sheets, the blank spaces are different. Since they can’t look at each other’s sheets, they have to do a lot of talking and thinking to complete their sheet. The student’s partner would have the B sheet, the mirror opposite of A. The order is different. That way students can’t just go “what’s the 2nd box on the first line.” Here are a few lines from the two different sheets so you can better visualize what I’m talking about.

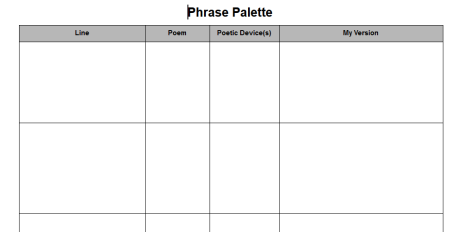

- Now that students have a resource they can turn to for figurative language, it’s time to dive into the language of the poems. I ask students to complete a “phrase palette,” a simple organizer where students copy down lines they love from our mentor texts, figure out what (if any) figurative language is going on in the line, and then try to copy it for their own slam poem. This is always harder than I think it will be, so plan accordingly. Here’s what it looks like blank.

- Once this is done, students fix up their drafts by revising their language. They use the information gap and phrase palette to help them. This is also when I do most of my individual conferring.

- The final step in this phase involves adding some killer rhymes to our poems. We begin by checking out/annotating/choral reading the best rhymes in the mentor texts we’ve been using. I do a short mini-lesson on inner and outer rhymes. I show them rhymezone.com. And then I give the class the first line of a poem about going to school. I tell them to write the next three lines of the poem, paying special attention to adding inner and outer rhymes. The key here is using a first line that has a lot of simple words to it. For instance, students had a lot of fun coming up with rhymes based on this first line: “I woke up, put some clothes on, and walked out the door.”

Presentation: Practice, practice, practice!

- To get ready, students read to the wall (your ears and eyes catch mistakes your brain misses), read to each other, record and listen to themselves reading, etc.

- I don’t do a lot of peer feedback because it’s an incredibly challenging skill that requires months and months of intentional practice. In my experience, students usually just pick at surface errors in each other’s writing. Afterall, this is what their teachers usually do to their work. The problem is that this doesn’t improve writing at all. It just makes folks not want to share.

- On the final day, I’ll throw anything and everything at kids to get them to present. Candy, extra points, names on the wall, whatever. We clap, hoot, holler, and snap every time we hear a great line.

Phew! That’s it. Like I said earlier, this unit produces amazing writing from my students. Many of them reference it as their favorite unit during the end of quarter/year reflections.

I put together a sparse Google folder with all of the handouts I referenced above. Feel free to take, copy, modify, whatever!

What Am I Doing? Coronavirus and the Teaching Unknown

We are in a global pandemic and everything has changed. Cortisol has flood my synapses. My neck, shoulders, and back feel like they’ve been fused together in a painful patchwork of rigor mortis. Some of this anxiety isn’t new; I’m always on edge. It’s in my guts.

That’s one of the many things I love about teaching. It harnesses and channels my anxiety. It shapes my nervous energy into a recognizable form that I’m intimately familiar with. It powers my lesson planning, classroom management, and entire teacher persona. It pushes me past the torpor that begins setting in anytime I’m directionless.

I’ve had a lot of time to feel directionless this week. The traditional boundaries that I’ve hewn to over the last decade have dissolved. My anxiety has nowhere to go. And in the closed network that is my neurological system, anxiety has to go SOMEWHERE. Otherwise it’s just a corrosive lake eating away at my insides.

Like many others, I hate being trapped in the gray, in those indeterminate spaces where options and vectors spin out. This is why I get extra antsy on snow days. As soon as it starts snowing, I become consumed with figuring out whether or not I’ll have to go into work the next day. It’s not the job that I hate (I LOVE TEACHING!), it’s the unknowing. Snow day anxiety is nothing compared to this.

Because I know what to do with a snow day. I play with my daughter. Watch movies. Bounce around the house stuffing my face with the heavenly cookies my wife bakes whenever inclimate weather strikes.

But this isn’t a snow day. It’s an unprecedented global pandemic that has upended the social and professional fabric of my life and the lives of my students.

Last Friday we were instructed to pack up our stuff and not come back until the middle of April. Four weeks. The guidelines for teachers in my district are anemic at best. We can post work, but it has to be review. Nothing new. And nothing can be graded. That’s it. These guidelines make sense, and I take no umbrage with them. I mean, what else am I supposed to be doing?

Well, based on the posts clogging my various teacher social media feeds, I should be downloading Zoom, holding video conferences with students, designing passion projects, etc. These things all sound great, but I’m not trained to do any of them. Distance learning is a legitimate subcategory of pedagogy with its own thought leaders, philosophical debates, and learning curve.

You don’t just start “doing” distance learning the same way you don’t just start teaching. Any teaching is serious, and anything serious requires intentional study and practice.

I’ve dipped my toes in and put some stuff online for my students. They have an online Coronavirus Notebook to help them keep track of their experiences throughout this historical moment. I give them daily focus questions and prompts. Insert a video time capsule where you record yourself talking about everything you’re eating, drinking, watching, feeling, and doing. Use a Creative Commons website to find an image that symbolizes your week and write about it. Etc.

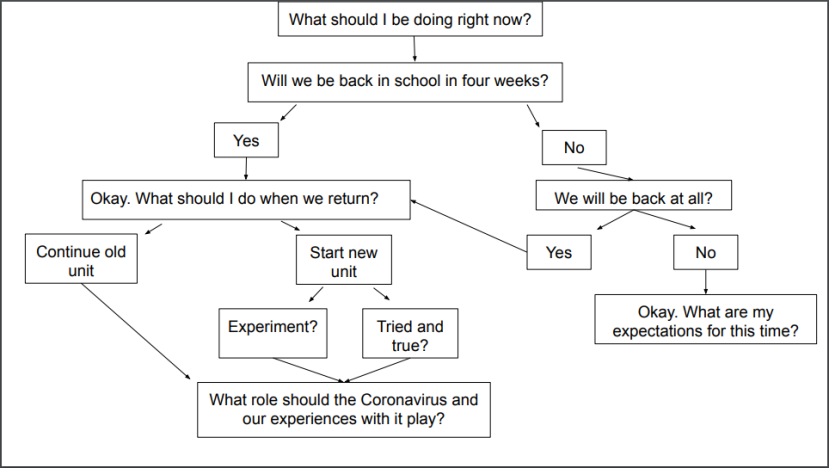

So is this all I’m supposed to be doing for the next three weeks? Let’s say that it is. That plugs up one stream of anxiety while opening up another. What am I supposed to do when I get back from these four weeks? Should it be new? Should it pick up where we left off with some minor modifications? What role should the Coronavirus play? How does my moral and professional duty as a teacher intersect with an unprecedented public health crisis?

I created a flowchart to capture the manic sequence that’s hamster-wheeling in my brain. Here it is.

It’s an endless loop. A recursive cycle that folds into itself the the more I try to pin it down. The second I stumble upon a fruitful avenue (maybe I could do a unit on X!), my anxiety barges in like a toddler, picking everything up and depositing it somewhere else. While screaming.

I can’t really think of a conclusion for this post, just like I can’t come to a conclusion about what’s going to happen in the coming days and weeks. The key for me is to avoid the analysis/paralysis that often results from trying to think about too many things from too many angles at once. So I’m going to stand up right now and make a sandwich.

Point Sheets Make Me Want to Barf

“HERE” Martin thrust a crumpled sheet of paper at me. Before my mind could figure out what I was supposed to do with this botched piece of origami, I noticed the telltale Google Docs table outline that could mean only one thing: a point sheet.

For the three folks reading this who aren’t teachers, a point sheet is a common method used by schools to try and shape a student’s behavior. Teachers and student decide on a couple of academic, behavioral, and social goals to focus on and track throughout the day. The goals are usually pretty standard: completes all classwork, comes to class prepared, etc. The kid carries around the point sheet with them from class to class. At the end of each class, the teacher is supposed to mark off on the sheet whether or not the student met the goals. Point sheets draw from crude behaviorist notions of behavior modification.

I smoothed out the paper on an empty desk, clicked my pen, grabbed my laser pointer, and read. The instructions were clear. Each of Martin’s teachers were to put a “1” or a “0” next to each goal. A 1 meant Martin needed fewer than two reminders, whereas a zero meant he needed more than two redirections.

Martin’s goals were as follows:

- Treat teachers and students with respect.

- Complete all classwork.

Regardless of the relative simplicity of the point sheet’s instructions, Martin’s sheet was covered with a variety of symbols. Some teachers went with a check/check minus/check plus system; some teachers used checks and X’s, and other teachers filed the margins with last minute explanations and commentary.

My brain poured through its videotape of the class period that had just ended. Doing this with the particular brand of objective fidelity required by the point sheet would be challenging under any circumstances. It was especially vexing in the unadulterated chaos that is the interstice between two class periods.

Martin hovered next to me, hopping from his left foot to his right as he waited and watched. “I did good today, right? Right, Mr. Anderson? I did good today. My mom really wants me to do good today. I’ll get my phone taken away by my dad if I get any bad marks. But I did good today, right? Better, for sure. Right?”

I mean, Martin DID do well today. But here’s the thing: it took an Herculean amount of effort to get him there. I parked myself next to him whenever I could. That way anytime he ran his mouth (which he was forever never not doing), I could steer his monologic flow back towards the assignment. He worked on his handout, but he didn’t complete it. So what does that mean for his point sheet? If I use a literal reading of the goal, then I would have no choice but to give him a zero. But what if I overplanned the lesson? What if the instructional sequence I designed for the day was confusing? Maybe Martin found neither value nor relevance in my lesson. In that case, am I just asking him to do what I tell him to just because? Do I want to be cultivating students who value compliance?

His second goal, being respectful, was equally challenging to capture in a yes/no binary. Throughout the class period Martin required multiple redirections and nonverbal cues to stay on task. He interrupted me, made fart sounds at a student, and shouted non-sequiturs during the warm-up. He was currently flashing the laser pointer he had deftly yoinked from my hand around the room, narrowly missing several students’ corneas.

I spend more energy on him than most of the other students in his class combined. If class were a pinball machine, I’d be the rubber bumpers and Martin would be the pinball. He keeps plummeting towards the bottom and I keep catching him and boosting him back up. The game is played at a feverish pace. There’s no end. I just try to avoid running out of quarters until the timer runs out.

But was he disrespectful? Were his actions throughout the 42 minute period indicative of someone who is unkind and malicious? Martin is a neurodiverse student who struggles to fit into the complex mazes of overly punitive policies that form the core of public schooling. I’m not familiar with his home life, but I’d bet my job on some form of trauma in his family history. I’m not making excuses, just trying to understand exactly what is going on with this intelligent, quick witted, and observant adolescent in front of me.

In many ways, the point sheet can be seen as a synecdoche for school. Despite whatever’s going on at home, despite the energy I’ve spent cultivating a relationship with Martin, regardless of the staggering amount of labor I’ve expended trying my best to create rigorous, engaging, and culturally relevant lessons, at the end of the day, it all comes down to a single mark. There is no room for nuance or complexity. When the needs are so great and the resources are so few, everything is flattened and reduced.

Exhausted, I sign off on his point sheet, grab the laser pointer, and tell him to go to his next class. He looks at my notations and shouts “LET’S GO!” before plunging head first into the throng of students milling around outside my room, knocking down a sixth grader and sending assorted books and pencils flying in the process.

Later that afternoon I pack up my stuff and head out of my room ready to go home when something catches my eye: Martin’s point sheet crumpled up and ground into the carpet. It must have fallen out when he careened into that sixth grader. I shove it into my pocket, telling myself I’ll check in with him first thing tomorrow morning. But I don’t. I forget. Thank goodness Martin doesn’t get to fill out a point sheet for me.

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

-For the sake of anonymity, this post draws inspiration from a variety of students. “Martin” is not a stand-in for any particular student but instead a composite of many of the wonderful kids I’ve been fortunate to work with.

“This Class is Easy” Some Minor Thoughts on Rigor in the Gradeless Classroom

I hate grading things. I have a lot of students and it takes too long and it doesn’t increase anyone’s ability to read, write, speak, or think critically. So I don’t do it. I haven’t done it in five years. Since my district requires a letter at the end of every quarter, students assign themselves a grade as part of their quarterly portfolios.

Most kids give themselves B’s. No one wants a C because that makes honor roll impossible. Families often hitch rewards and punishments to report cards. Other students are nervous about giving themselves an A because they think I’ll challenge it. Rarely do I give out anything lower than a C. First, it feels icky to go nine weeks without mentioning grades and then suddenly become tyrannical about them. Kids would feel sucker punched.

Second, low grades also don’t increase student learning. Kids who aren’t turning in assignments or engaging with the content aren’t doing so because I haven’t dangled enough carrots from the stick. Everyone wants to do well and find success. Students struggling with this need things like strategies, compassion, consistency, and support. Not grade shaming.

Don’t misunderstand me. High expectations can and should exist without grades. I’ve found that maintaining the expectation of excellence is harder to do in the gradeless classroom. This comes from students telling me that my class is easy. They say the lack of grades lowers their anxiety. They don’t have to cram for unit tests or drill Kahoots to memorize terms.

That makes sense. We tend to equate intellectual rigor as something that can only happen if a student is stressed out and anxious. Something is only hard if it threatens our grades. This is a totally rational response to a system that prizes extrinsic rewards above anything else.

My ability to engage students without relying on grade-related threats will probably always be a struggle. It’s a Sisyphean goal. Yes, I work to cultivate meaningful relationships and build a classroom environment that fosters intellectual risk taking. I try to locate authentic audiences for student work and articulate clear purposes for every assignment. But at the end of the day, not everything can be fun and work stinks.

Grades aren’t going anywhere. They’re too baked into the system. There’s no way to move massive numbers of students up and down grades and in and out of different schools without some sort of standardized reporting. The inertia behind standard grade reporting feels insurmountable. Besides, there are more pressing issues to focus on such as educational inequity and structural racism. While grades can be understood as a manifestation of oppressive assessment systems, a focus on removing grades can easily miss the forest for the trees.

I don’t plan on returning to grades. It’s on me to engage students through my curriculum and instruction while leveraging as little extrinsic motivation as possible. If students are only working for the grade, then I haven’t done my job. That’s my favorite part about going gradeless. It forces me to fight for my subject matter and my discipline. I get to spend every day making the case for why this stuff matters.

Do You Enjoy This Class? Using Anonymous Surveys for Feedback

“This classroom is not a place where I’m able to learn because of the noise levels.”

“A group of students make it hard to work because of giggling and talking.”

“I do not feel respected by my classmates because of how some people act.”

These statements greeted my sixth period students as they entered the room two weeks ago. After everyone was seated, I asked them to reflect on what they saw. Did these statements accurately reflect what was going on in the room? After a brief discussion, I told students that I would make sure that they always knew what the expectation was. If an activity called for them to be silent, we would take ten seconds to practice what that looked like and sounded like. Students who struggled to meet the expectations would meet with me to talk through strategies and work on self-awareness. Not as a punishment, but as a chance to figure out what’s going on and how to work towards improvement.

The talk (and a couple of reminders since then) has led to a drastic improvement in the classroom environment. And it’s all thanks to the feedback of three anonymous students.

As teachers we’re inundated with feedback. Most of it comes through bureaucratic channels such as checklists, official forms, Likert scales, missives, spreadsheets, and percentages. This sort of feedback can be hit or miss. It’s often tied to faceless initiatives and whatever mandate is big in the edu-sphere at the moment. The feedback that matters most, the kind at the top of this post, can be the hardest to find. What do my students think about what’s going on in our class? Does my instructional style work for them? This type of feedback is built on trust and reciprocity between teacher and student.

There’s different ways to collect this kind of data, and each method provides a slightly different take. Meeting with a core group of students over a period of time, a la Chris Emdin’s cogenerative dialogues, helps you tap into how students experience your class on a day to day basis. What lessons worked? What discussions fell flat? Writing back and forth with students and their families in a notebook can provide a comprehensive portrait of how everyone is doing inside and outside of the room. Unfortunately it requires a dizzying amount of labor to pull off on a consistent basis. Luckily there will always be some kids who will just tell you when the lesson sucked. Like most teachers I rely on a combination of these methods.

I also like to do a simple “State of the Class” survey. I prefer to use an anonymous Google Form. Here’s a past example if you’re curious. It gives me a snapshot of how kids feel about me, my instruction, and our class. Some of the questions have to do with classroom environment (Do you enjoy English class? Is English class a place where you can focus on learning?) while others focus on instruction (Which of the following activities helped you improve as a writer?) My favorite answers come from the open response questions about how Mr. Anderson can improve. The answers mirror the period. I must admit, I put a couple more questions about classroom environment on my last survey because of sixth period specifically. In this case the feedback confirmed my own perceptions.

Going through the survey responses, I often get the feeling that I’m working too hard. That the time I spend massaging fonts and presentation slide syntax probably isn’t worth it. Do I want every unit to be a panoply of epiphanic activities and brilliantly sequenced lessons? Of course! But for a lot of kids, it’s just class. And that’s okay. I’m not going to lie and act like I don’t go home and agonize over every survey that reveals a kid doesn’t absolutely love my class. But it’s a necessary reminder. I also enjoy sharing the data with students. That way if anyone groans about reading, I can remind them that 73% of students asked for more independent reading time.

Whether you give a survey, write back and forth, or meet with kids during lunch or after school, the feedback you receive is invaluable. Do kids like your class? Do they feel respected? Do they feel like they’re learning? This sort of feedback cuts through the noise and hierarchies and gets at some of the most important questions to any teacher.

When Teaching Narrative, Go Realistic Instead of Personal

Personal narratives are a staple of the secondary English curriculum. I love writing about myself, so why shouldn’t my students? Typically I would push the kids to mine their past for meaningful moments. Students understood this to mean write about something painful. I even had the audacity to get upset anytime students pushed back. This is what writing’s about! I would thunder. It’s not really, though. Or at least it doesn’t have to be. It certainly shouldn’t be for every student.

This year I switched from personal to realistic narratives. I decided it was inappropriate to continue to enact a pedagogy of disclosure. Pedagogies of disclosure require students to relive potentially traumatic experiences AND hold them up for critical feedback from teacher and peer. I had to take a step back, remind myself that I’m an English teacher, and that stories are about windows and mirrors. Vehicles through which we find out we’re not alone and that our lives carry significance.

Realistic narratives can do all that. We brainstormed various protagonists, motivations, obstacles, and settings. We used stage directions and acted out dialogue. There was feedback, revision, and editing. All the typical personal narrative skills without any of the icky required disclosure stuff.

My favorite part was tinkering with made-up details that served the piece without setting off the reader’s BS alarm. I told students that realistic narratives allowed writers to shape their past into whatever they wanted. There was capital T Truth (your airtight memory), little t truth (a detail that might not have been exactly right but served the same purpose), and fabrication.

This genre-bending challenged most of my students, and understandably so. Molding raw experience and trenchant observation into purposeful prose takes decades to master.

As always, I wrote alongside them. I chose one of my few middle school memories: an 8th grade party. I delighted in asking them to guess which parts of my narrative were fictional. I included my realistic narrative below. It’s pretty melodramatic, and it’s obviously the work of an amateur. I wasn’t even able to “finish” it. But that’s part of the challenge (and elation) of writing alongside your students. It knocks you off of your pedestal and humbles you before the power of the word, the story, and the audience.

I can’t wait to try this again next year, this time with an emphasis on fabricating and borrowing details. The unit was a success and students reported a high level of enjoyment. Next time you reach for your memoir or personal narrative lessons, consider shifting towards realistic.

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

Title: Only in Dreams

Colorful holiday lights hung from the ceiling, casting a warm glow over the room. Red, pink, green, and blue reflected off of our faces as my friends and I alternated between talking in groups, chugging soda, and chomping on chips and pizza. We were all in Cheryl’s basement. She lived in a giant house in the country club hills neighborhood of Arlington. Her parents popped downstairs every 30 minutes or so to check in on us and make sure everything was going well.

I had been dying to ask Alicia to dance the entire night. It was the party for our 8th grade graduation, and this would be my last chance. She stood across the room disappearing in and out of a group of her closest friends. Alicia was about my height. She had an athletic frame from years of playing travel soccer. She was everything I was not. Sarcastic, quick witted, responsible, and decisive. Her ability to talk trash was legendary. No one dared to try and roast her. I would catch flashes of her dirty blonde hair as she laughed and danced with her friends.

It was one of those moments when you’re trying not to stare at someone, but that somehow makes you stare at them even more. And everytime our eyes locked, my palms itched and my scalp tingled and my heart threatened to jump out of my throat. Every time I tried to approach her, something would happen. A rock song would come on and my buddy Jeff would tackle me. Or two kids would start roasting each other and everyone would crowd around them to watch.

Time was running out. The party ended at 9, and it was already 8:35. Cheryl’s mom had come downstairs and recruited people to move to start picking up. At 8:40 the main basement lights came back on, killing the vibe. I didn’t know what to do.

Peter: (Moping on the floor, sounding rejected) It’s almost over and I still haven’t asked her to dance!

Jeff: (Punching Peter on the shoulder. Speaking with confidence) Just get up and do it. She’s right over there. Come on, man!

Peter: (Stuttering his words) It’s not that easy for me. Girls love you. I’m, well, me.

Jeff: (laughing) Yea. Not gonna lie; that’s true.

Peter: (whispering quickly) Dude she’s coming over!

Jeff: Go on, get up! (Trying to push Peter up)

Alicia: (Walks over confidently. Sticks out her hand) Okay. Come on.

Peter: (face flushing, looking at Jeff who suddenly jumps up and leaves to get some soda) Wait, what? I mean… what?

Alicia: (Sighing) Don’t you want to dance? (Looking over at her friends) Everyone told me you did.

Peter: (Looks over at Jeff by the drink table)

Jeff: (Nods enthusiastically)

Peter: (Nervously) Okay (takes her hand)

I looked back at Jeff as she dragged me into the middle of the room with surprising force. The opening bass riff from Weezer’s “Only In Dreams” started to ooze out of the speakers.

I didn’t know exactly what to do, and neither did she. She rested her hands on my shoulders and the two of us started to rock awkwardly back and forth. My palms heated up like I was holding onto an exploding star. Strawberry perfume floated up as I felt her place her cheek on my shoulder. Jeff snuck around behind her and started making faces to try and get me to laugh. It worked. Alicia whipped her head up and stared at me. “Jeff’s doing something dumb, isn’t he?” She said.

“Yup!” I replied.

“You guys are idiots,” she smiled. “So where are you going to high school?”

“Yorktown,” I said. “Aren’t you going to some private school in Georgetown, or something?” I knew exactly where she was going, but this would keep her talking.

“Yea. Sidwell Friends. I’m actually pretty excited. They have an awesome girls soccer team.”

“Thanks for asking me to dance,” I whispered.

She tucked a strand of her behind her ear and smiled. “I’m glad we got to do this,” she said.

For the next two and a half minutes, the only thing that mattered was the two of us swaying gently in time to the music. She kept her head on my shoulder and I kept myself from stepping on her toes.

Before the song could end, Cheryl’s mom hollered down into basement that my mom was there to pick me up. I said goodbye to Alicia, Jeff, and my other friends before bolting up the stairs. On Monday at school, Alicia and I said “hi” a few times, but that was it. It was almost like the dance had never happened. A few days later we went our separate ways to different high schools. We ran in different crowds and I never saw or heard about her again.

Try Writing with Your Students

Teaching students how to write is really hard. Students need direct instruction, engaging “real world” models, time to write and revise, an audience they care about, and assignments that appeal to them. Even on the best of days when we’ve somehow managed to tick off all of these boxes, we still have to wrangle with the morass of hormones and developmentally appropriate inattention that is the hallmark of a middle schooler.

Like most teachers, I’m constantly swapping out new (and old) writing pedagogies in search of anything that will get my students excited about their writing. But no matter what instructional methods I’m trying out, one tool remains consistent: writing alongside my students. I don’t mean cobbling something together to offer as a finished product to emulate, but actually getting down into the trenches sweating it out word for word with them on every assignment.

This does a few things. It helps me treat writing seriously and unseriously. Both perspectives are necessary for a writer. It’s also a quick way to find out whether or not an assignment sucks. Working on a piece of writing alongside my students helps me see the nuts and bolts of the assignment. The more I do it, the better I become at predicting where the sticking points will be. Which areas I can gloss over and which skills will require a deep dive. It gives me a chance to demystify the writing process and show students just show much work goes into crafting something even semi-coherent.

When I write with my students, I send the message that what we’re doing in the classroom is worthy of serious time and effort. And that we’re in it together. The feedback goes both ways.

The call for teachers to write with their students is nothing new. A debate about the efficacy of writing alongside students raged across the pages of NCTE’s English Journal in the nineties when high school teacher Karen Jost argued that the time it takes for teachers to write is better spent conferring with students. Teachers already have too much to do, she explained. The demand that teachers of writing now themselves should be writing smacked as yet another example of teachers being told what to do by supposed thought leaders who hadn’t stepped foot in an average classroom in years.

In many ways Jost wasn’t wrong. There is no time. It’s impossible for me to do everything I’m supposed to do. Every day is a series of cost/benefit decisions. I get one 45 minute planning period unmolested by meetings a day. Do I spend it in an IEP meeting that will surely go into my lunch break? Or do I use that time to provide written feedback on student writing? But if I do either of those, I won’t be able to finally meet with that student who has been writing about how bad his depression has gotten. I also need to check in with the counselor about a student’s math placement and think ahead to tomorrow’s lesson. Few of my options deal directly with classroom instruction and the Herculean task of growing readers and writers. So I understand why asking teachers to begin writing with their students seems like just another task.

But that the decision to write alongside our students isn’t a binary choice. It’s more of a stance we take towards curriculum, instruction, and our place inbetween. A teacher as writer stance connects us with the art and science of writing in a way that no rubric or exemplar ever could. It’s the best way to learn that a piece of writing’s center of gravity changes multiple times throughout the writing process. Or that no matter how hard an author wrestles with a piece, sometimes it just doesn’t work out.

To get started, consider one place you can write with your students. A brainstorming session for an upcoming essay or poem, for instance. The good thing about students not being used to their teachers writing is that they won’t call you out if you don’t follow through on it.

Writing alongside your students will fundamentally alter your relationship with what you teach, how you teach it, and how you relate to students. And as this relationship begins to shift, so will your relationship to the writing instruction that’s going on around you. You will (re)connect with the transformative potential of literacy and the power of words to bind us together. It’s a way to come home to a profession that seems so bent on throwing up hurdles between what we do and why we do it.

Back to School Night

My back to school night dread begins in August. The ecstatic joy that is the first few days of the school year is always tempered by the dismal knowledge that in a few weeks I’ll be staying at work until well past my octogenarian approved bedtime.

Rationally I know back to school night isn’t a big deal. It just comes at such a rotten time. It’s always crammed into the third week of school when teacher morale is in the dumpster. The euphoric mixture of adrenaline and dopamine characterizing the first ten days of school has been replaced by the sobering realities of overstuffed classrooms, soul crushing bureaucratic demands, and germs. So many germs. Luckily September’s cocktail of choice, a noxious mixture of convenience store coffee and generic Dayquil, keeps me wired enough to get through the gauntlet that hits the third thursday of every September.

The actual night itself is a blast. I love talking to families. Old students come by and stalk the halls like they own the place. Every now and then a student who I haven’t seen in years will pop their near unrecognizable head (the changes from puberty are no joke) into my room and chat for a few minutes. This year’s pop-in was especially memorable.

Many years ago, I taught a student who was fascinated with drawing, thinking about, and talking about animals. They would stop by to show off their most recent artistic creations. A hippo with the head of a capybara. Some multisyllabic dinosaur combined with the spots of a giraffe. And accompanying each image, of which there were many, would be an intensely detailed description of the animal’s biome, mutations, and evolutionary stages.

I was never particularly interested in animal science. It was the kid’s joy that kept me engaged. They were just so infatuated with this stuff that I couldn’t help but grin and follow along with every obscure detail. I don’t think it mattered too much what I said or did, just that I was there. They would plop down at a desk, open up their notebook, and let it rip.

And then they were gone. They graduated and that was it. Until last week when they stopped by to visit me before back to school night began.

It was a joyous reunion. Nothing had changed. We had barely finished shaking hands before they brandished their latest notebook and guided me through their most recent illustrations. They’d even brought some of their original drawings to show me how their artistry had evolved. They told me about a blog they’d been keeping where they chronicled many of their creations. And about the friends they’d made who shared their interests.

They could only stay for a few minutes, but that’s all we needed. The muscles in my cheeks ached from smiling. Every cell in my body was grinning. Theirs were too, I think. It was the perfect way to begin an evening of confronting the high stakes privilege that is teaching language arts to the hearts and minds of young people.

A few moments families began flowing into the room, jostling each other to find space in a room built to accommodate the physical proportions of 7th graders. I did my best to reveal who I was as a teacher. What I hoped to accomplish with their children and how I was going to do my best to help them grow.

The next morning, as I sipped my coffee and chugged my Dayquil, an email from that student appeared in my inbox asking if I could read and provide feedback for something they had written. It’s a story about a group of humans who hunt dragons with futuristic technology on a harsh planet. I can’t wait.

Trying To Make It Fit: Nine Weeks In The System

For the last few years, I’ve been one of those “I just close my door and teach what I want” teachers. I’ve outright rejected the pedagogical norms of my school to pursue my own path. I’ve refused to create common assessments. My hermitude became a badge of honor. I saw myself as an outsider fighting the good fight.

It wasn’t until I began working on an essay with Julie Gorlewski that I realized the fundamental error in my thinking. The essay explored the dual roles of teachers: we are both and always agents of the state and agents of change. Closing my classroom door to the world granted me autonomy, but it alienated me and hampered my ability to work with others. I had turned my back on my colleagues and on my community.

So when this school year started, I decided to try and work within the system. This has meant a slew of changes. Some of the switches were small. For instance, I now begin every class by leading students through an “I can” learning outcome. Although I agree with Joe Bower and Jesse Stommel that fixed outcomes cut off authentic inquiry, my administration expects them. Other shifts have been more dramatic. For the first time in years, I’m now teaching what I’m officially supposed to be teaching. I even signed up to be part of a curriculum writing team. What better way to have the social justice and anti-racist curriculum I craved?

The process has not progressed as I thought it would. Faced with more academic standards than could possibly be taught with any level of depth, I’ve struggled with making social justice a priority. Our next unit is 3-4 weeks long. In it we’re supposed to teach students to use context clues; identify prefixes, suffixes, and roots; distinguish between fact and opinion; analyze persuasive techniques in media; identify organizational patterns; make inferences and draw conclusions; identify the main idea; and use text features to skim a text. This is on top of the general English Language Arts stuff of developing a love of literacy and reading and writing authentically.

It’s certainly possible to pursue these outcomes in a way that helps students read both the word and the world, but it takes a committed effort. It has to be the thing, not something extra. Butting heads with my colleagues has given me ample opportunity to reflect on Robin DiAngelo and Ozlem Sensoy’s reminder that “Because dominant institutions in society are positioned as being neutral, challenging social injustice within them seems to be an extra task in addition to our actual tasks” (141).

Making the cognitive and perceptual leap from “we have to cover these standards” to “who benefits from these standards, who loses out, and how can we prepare for democratic citizenry?” is as difficult as it is essential. But until everyone in the room acknowledges the inherently political nature of teaching and learning, ‘finding room’ for social justice and anti-racism is all but impossible.

The way we discuss and envision critical thinking and democracy must also change. In my experience, schools tend to define critical thinking as the process of identifying problems and inventing solutions. This frames students as capitalists and problem solving as opportunities for entrepreneurship. In a social justice context however, critical thinking refers to “a specific scholarly approach that explores the historical, cultural, and ideological lines of authority that underlie social conditions” (1).

And when it comes to democracy, mainstream education casts schools as instruments to educate for democracy. Schools produce democratic citizens by informing students about history, the importance of peaceful protest, and the power of voting. In contrast to this, Gert Biesta discusses education through democracy. A continuous process of learning to value and exist alongside those who are fundamentally not like us (120). Schools can support society in this work, but they cannot create, sustain, or save democracy. And what this would even look like in a public school classroom, I have no clue.

Back inside the classroom, I’ve had a much easier time implementing aspects of culturally responsive/culturally proactive teaching. My students use a variety of discussion and response protocols, combine their out-of-school interests with traditional academic skills, and build knowledge through collaboration and discussion. But most of this gets at the how, leaving the what largely intact. And the what is what I’m interested in changing.

I don’t know how to reorient my classroom around social justice and anti-racist pedagogy, yet. For now, I’ll continue teaching the official units, working with the curriculum team, and looking for ways to exist in that interstitial zone between thesis and antithesis, as an agent of the state and an agent of change.

——————————-

Photo by Hans-Peter Gauster on Unsplash