Category: Writing

Distance Learning Resource Round-Up for the 2020-2021 School Year

Hi! I teach English Language Arts to middle schoolers.

The idea of beginning the year 100% virtually makes me shit my pants from anxiety. In order to ease some of this distress, I spent the last few days compiling a list of everything I thought might be useful as we begin the 2020-2021 school year. While doing so didn’t help my nerves, I’m hoping it might be helpful to you!

If you want, you can also access the original Google Doc here or simply scroll down below.

See a link that looks good? RIGHT CLICK ON IT AND OPEN IT IN A NEW TAB. Otherwise it might not open in WordPress.

I’m sure I’ll keep tinkering with it over the next few weeks. ENJOY!

Speaking Your Truth Through Slam Poetry: A Unit Overview

“We’re doing poetry? I haaaaaaate poetry! It’s SO boring, Mr. Anderson!”

One of the easiest ways to make a room full of middle schoolers groan is to say the word “poetry.” I don’t blame them. The thought of analyzing the theme of “Hope is the Thing with Feathers” or any of the other nature themed poems that regularly pop up on standardized tests makes my eyes slide back inside my head.

A few years ago I began teaching a unit on slam poetry. Students responded immediately to slam poetry’s relevance, topics, and overall style. Slam poetry feels vibrant and current. And thanks to the internet, teachers now have access to cutting edge slam poetry written by people that look and sound like their adolescent students. I’ve taught this unit three years in a row, and it never fails to produce some of my students’ strongest writing of the year.

What follows is my basic blueprint for my annual slam poetry unit. This unit combines “just right” mentor texts with rock solid instructional activities. Because it requires students to be vulnerable, I typically save the unit for the back half of the school year. That way I’ve had time to build and sustain a sense of classroom community with students. Without vulnerability, slam poetry is nothing.

Unit Title: Speaking Your Truth through Slam Poetry

Time Length: Five weeks of 42 minute class periods

Final Product: Students will write, revise, and submit an original slam poem. While students do not have to present, they are encouraged.

Standards: These are from Virginia. I’m sure most states/Common Core have something similar.

- describe the impact of word choice, imagery, and literary devices on different poems (7.5d)

- analyze the themes of various poems (7.5a)

- write, revise, and edit original poetry that that incorporates word choice, imagery, and literary devices (7.7d, g, j)

Mentor Texts: Ten years of teaching English Language Arts has taught me that providing students with engaging, developmentally appropriate, and culturally responsive mentor texts from the “real world” is the most essential component of a successful unit. To that end, I’ve collected every slam poem I’ve ever used into a mentor text packet for you to make a copy of. Every poem in this mentor text packet has a corresponding YouTube video of the poet delivering (or ‘slamming’) their poem.

Content Warning: If you plan on using these poems, make sure you read through them first. For some of the poems I give a content warning and provide students with a chance to sneak out first. The poems here deal with topics such as: anxiety, depression, grief, ADHD, race, gender, substance abuse, technology, and religion.

Basic Instructional Sequence: The basic instructional sequence for this unit is adapted from the mentor text model described by Katie Wood Ray in Study Driven. Students begin by “immersing” themselves in slam poems. They listen, discuss, read, and write. The next step asks students to “write under the influence” of the mentor texts. Finally, students use specific texts and techniques to revise and deliver their poems.

Immersion Phase: Expose to students to the mentor texts. Get them reading, writing, and talking about them.

- Introduce the genre with a high interest slam poem (You can never go wrong with Touchscreen). Help students identify the difference between first and second draft reading. The former helps students access the content (the WHAT of the poem) while the latter gives students a way to analyze the craft moves made by the poet (the HOW of the poem).

- Introduce one poem a day to students. Watch them multiple times. Read them multiple times. Give students room to respond to the poems in a way that suits them. This is where I introduce “punctuation annotations.” Students read through the poems and mark up the lines with hearts, exclamation marks, question marks, etc. What surprises them? What lines can they identify with? Etc.

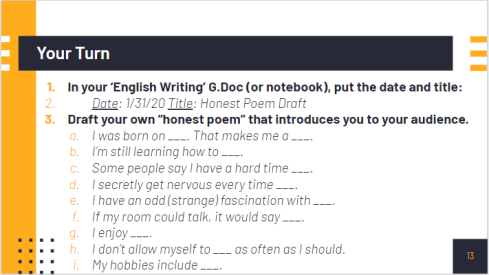

- Then, have students use the basic framework of the day’s poem to generate their own version. The goal here is to give students their own bank of writing to draw from when it comes time to commit to a draft. I always give students two options. They can just “go for it” and write something with the mentor poem on top of their brain. Or they can use a “poem frame,” a more sophisticated fill-in-the-blanks. This requires the teacher to use a poem with an easily identifiable and copyable format. Below is one of the slides I used from the excellent Honest Poem by Rudy Francisco. The bullet points on the slide come from lines in the poem that I adapted.

- Students end this phase filling out a simple “What is slam poetry?” handout. It has four basic questions about what slam poetry is, how it’s different from more traditional forms of poetry, and what they can write about for their own poems. Students have immersed themselves in slam poetry for about a week at this point, so there isn’t much scaffolding or direct instruction that happens here.

Writing under the influence: Students use the mentor texts as guides to help them write their own poems.

- The goal of this short phase is for students to complete their “down draft.” To just get something “down” on the paper. We’ll fix it “up” in the next phase.

- Students are encouraged to “talk back” to any ideas or stereotypes others might have about them. I typically introduce this idea by asking students to tell me what they assume about teachers. That we have no lives. That we live at school. That we hate kids. You can spend as much/little time with this as you want.

- Students can use any of their poem quick writes from the previous classes.

- Students can practice “lifting a line,” a simple technique where students pick a favorite line from a poem and use that to either begin or end their own original poem.

- I try to help them focus on quantity instead of quality at this stage. I shout “JUST WRITE!” a lot during this time.

Using Mentor Texts to Revise and Polish: This is where the real work comes in! Now that most students have a workable draft, it’s time to begin the labor intensive process of revision.

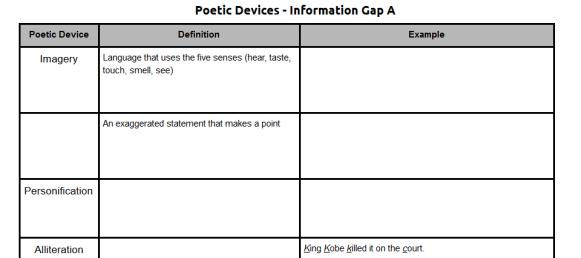

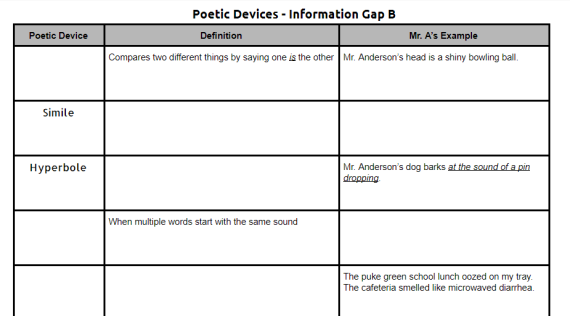

- To make sure we’re all on the same page with language, we begin this step by tabling our drafts and diving into language with an “information gap” activity. Students partner up, sit back to back, and try to fill in the blank spaces on their handouts. While each student has the same information on their sheets, the blank spaces are different. Since they can’t look at each other’s sheets, they have to do a lot of talking and thinking to complete their sheet. The student’s partner would have the B sheet, the mirror opposite of A. The order is different. That way students can’t just go “what’s the 2nd box on the first line.” Here are a few lines from the two different sheets so you can better visualize what I’m talking about.

- Now that students have a resource they can turn to for figurative language, it’s time to dive into the language of the poems. I ask students to complete a “phrase palette,” a simple organizer where students copy down lines they love from our mentor texts, figure out what (if any) figurative language is going on in the line, and then try to copy it for their own slam poem. This is always harder than I think it will be, so plan accordingly. Here’s what it looks like blank.

- Once this is done, students fix up their drafts by revising their language. They use the information gap and phrase palette to help them. This is also when I do most of my individual conferring.

- The final step in this phase involves adding some killer rhymes to our poems. We begin by checking out/annotating/choral reading the best rhymes in the mentor texts we’ve been using. I do a short mini-lesson on inner and outer rhymes. I show them rhymezone.com. And then I give the class the first line of a poem about going to school. I tell them to write the next three lines of the poem, paying special attention to adding inner and outer rhymes. The key here is using a first line that has a lot of simple words to it. For instance, students had a lot of fun coming up with rhymes based on this first line: “I woke up, put some clothes on, and walked out the door.”

Presentation: Practice, practice, practice!

- To get ready, students read to the wall (your ears and eyes catch mistakes your brain misses), read to each other, record and listen to themselves reading, etc.

- I don’t do a lot of peer feedback because it’s an incredibly challenging skill that requires months and months of intentional practice. In my experience, students usually just pick at surface errors in each other’s writing. Afterall, this is what their teachers usually do to their work. The problem is that this doesn’t improve writing at all. It just makes folks not want to share.

- On the final day, I’ll throw anything and everything at kids to get them to present. Candy, extra points, names on the wall, whatever. We clap, hoot, holler, and snap every time we hear a great line.

Phew! That’s it. Like I said earlier, this unit produces amazing writing from my students. Many of them reference it as their favorite unit during the end of quarter/year reflections.

I put together a sparse Google folder with all of the handouts I referenced above. Feel free to take, copy, modify, whatever!

When Teaching Narrative, Go Realistic Instead of Personal

Personal narratives are a staple of the secondary English curriculum. I love writing about myself, so why shouldn’t my students? Typically I would push the kids to mine their past for meaningful moments. Students understood this to mean write about something painful. I even had the audacity to get upset anytime students pushed back. This is what writing’s about! I would thunder. It’s not really, though. Or at least it doesn’t have to be. It certainly shouldn’t be for every student.

This year I switched from personal to realistic narratives. I decided it was inappropriate to continue to enact a pedagogy of disclosure. Pedagogies of disclosure require students to relive potentially traumatic experiences AND hold them up for critical feedback from teacher and peer. I had to take a step back, remind myself that I’m an English teacher, and that stories are about windows and mirrors. Vehicles through which we find out we’re not alone and that our lives carry significance.

Realistic narratives can do all that. We brainstormed various protagonists, motivations, obstacles, and settings. We used stage directions and acted out dialogue. There was feedback, revision, and editing. All the typical personal narrative skills without any of the icky required disclosure stuff.

My favorite part was tinkering with made-up details that served the piece without setting off the reader’s BS alarm. I told students that realistic narratives allowed writers to shape their past into whatever they wanted. There was capital T Truth (your airtight memory), little t truth (a detail that might not have been exactly right but served the same purpose), and fabrication.

This genre-bending challenged most of my students, and understandably so. Molding raw experience and trenchant observation into purposeful prose takes decades to master.

As always, I wrote alongside them. I chose one of my few middle school memories: an 8th grade party. I delighted in asking them to guess which parts of my narrative were fictional. I included my realistic narrative below. It’s pretty melodramatic, and it’s obviously the work of an amateur. I wasn’t even able to “finish” it. But that’s part of the challenge (and elation) of writing alongside your students. It knocks you off of your pedestal and humbles you before the power of the word, the story, and the audience.

I can’t wait to try this again next year, this time with an emphasis on fabricating and borrowing details. The unit was a success and students reported a high level of enjoyment. Next time you reach for your memoir or personal narrative lessons, consider shifting towards realistic.

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

Title: Only in Dreams

Colorful holiday lights hung from the ceiling, casting a warm glow over the room. Red, pink, green, and blue reflected off of our faces as my friends and I alternated between talking in groups, chugging soda, and chomping on chips and pizza. We were all in Cheryl’s basement. She lived in a giant house in the country club hills neighborhood of Arlington. Her parents popped downstairs every 30 minutes or so to check in on us and make sure everything was going well.

I had been dying to ask Alicia to dance the entire night. It was the party for our 8th grade graduation, and this would be my last chance. She stood across the room disappearing in and out of a group of her closest friends. Alicia was about my height. She had an athletic frame from years of playing travel soccer. She was everything I was not. Sarcastic, quick witted, responsible, and decisive. Her ability to talk trash was legendary. No one dared to try and roast her. I would catch flashes of her dirty blonde hair as she laughed and danced with her friends.

It was one of those moments when you’re trying not to stare at someone, but that somehow makes you stare at them even more. And everytime our eyes locked, my palms itched and my scalp tingled and my heart threatened to jump out of my throat. Every time I tried to approach her, something would happen. A rock song would come on and my buddy Jeff would tackle me. Or two kids would start roasting each other and everyone would crowd around them to watch.

Time was running out. The party ended at 9, and it was already 8:35. Cheryl’s mom had come downstairs and recruited people to move to start picking up. At 8:40 the main basement lights came back on, killing the vibe. I didn’t know what to do.

Peter: (Moping on the floor, sounding rejected) It’s almost over and I still haven’t asked her to dance!

Jeff: (Punching Peter on the shoulder. Speaking with confidence) Just get up and do it. She’s right over there. Come on, man!

Peter: (Stuttering his words) It’s not that easy for me. Girls love you. I’m, well, me.

Jeff: (laughing) Yea. Not gonna lie; that’s true.

Peter: (whispering quickly) Dude she’s coming over!

Jeff: Go on, get up! (Trying to push Peter up)

Alicia: (Walks over confidently. Sticks out her hand) Okay. Come on.

Peter: (face flushing, looking at Jeff who suddenly jumps up and leaves to get some soda) Wait, what? I mean… what?

Alicia: (Sighing) Don’t you want to dance? (Looking over at her friends) Everyone told me you did.

Peter: (Looks over at Jeff by the drink table)

Jeff: (Nods enthusiastically)

Peter: (Nervously) Okay (takes her hand)

I looked back at Jeff as she dragged me into the middle of the room with surprising force. The opening bass riff from Weezer’s “Only In Dreams” started to ooze out of the speakers.

I didn’t know exactly what to do, and neither did she. She rested her hands on my shoulders and the two of us started to rock awkwardly back and forth. My palms heated up like I was holding onto an exploding star. Strawberry perfume floated up as I felt her place her cheek on my shoulder. Jeff snuck around behind her and started making faces to try and get me to laugh. It worked. Alicia whipped her head up and stared at me. “Jeff’s doing something dumb, isn’t he?” She said.

“Yup!” I replied.

“You guys are idiots,” she smiled. “So where are you going to high school?”

“Yorktown,” I said. “Aren’t you going to some private school in Georgetown, or something?” I knew exactly where she was going, but this would keep her talking.

“Yea. Sidwell Friends. I’m actually pretty excited. They have an awesome girls soccer team.”

“Thanks for asking me to dance,” I whispered.

She tucked a strand of her behind her ear and smiled. “I’m glad we got to do this,” she said.

For the next two and a half minutes, the only thing that mattered was the two of us swaying gently in time to the music. She kept her head on my shoulder and I kept myself from stepping on her toes.

Before the song could end, Cheryl’s mom hollered down into basement that my mom was there to pick me up. I said goodbye to Alicia, Jeff, and my other friends before bolting up the stairs. On Monday at school, Alicia and I said “hi” a few times, but that was it. It was almost like the dance had never happened. A few days later we went our separate ways to different high schools. We ran in different crowds and I never saw or heard about her again.

Try Writing with Your Students

Teaching students how to write is really hard. Students need direct instruction, engaging “real world” models, time to write and revise, an audience they care about, and assignments that appeal to them. Even on the best of days when we’ve somehow managed to tick off all of these boxes, we still have to wrangle with the morass of hormones and developmentally appropriate inattention that is the hallmark of a middle schooler.

Like most teachers, I’m constantly swapping out new (and old) writing pedagogies in search of anything that will get my students excited about their writing. But no matter what instructional methods I’m trying out, one tool remains consistent: writing alongside my students. I don’t mean cobbling something together to offer as a finished product to emulate, but actually getting down into the trenches sweating it out word for word with them on every assignment.

This does a few things. It helps me treat writing seriously and unseriously. Both perspectives are necessary for a writer. It’s also a quick way to find out whether or not an assignment sucks. Working on a piece of writing alongside my students helps me see the nuts and bolts of the assignment. The more I do it, the better I become at predicting where the sticking points will be. Which areas I can gloss over and which skills will require a deep dive. It gives me a chance to demystify the writing process and show students just show much work goes into crafting something even semi-coherent.

When I write with my students, I send the message that what we’re doing in the classroom is worthy of serious time and effort. And that we’re in it together. The feedback goes both ways.

The call for teachers to write with their students is nothing new. A debate about the efficacy of writing alongside students raged across the pages of NCTE’s English Journal in the nineties when high school teacher Karen Jost argued that the time it takes for teachers to write is better spent conferring with students. Teachers already have too much to do, she explained. The demand that teachers of writing now themselves should be writing smacked as yet another example of teachers being told what to do by supposed thought leaders who hadn’t stepped foot in an average classroom in years.

In many ways Jost wasn’t wrong. There is no time. It’s impossible for me to do everything I’m supposed to do. Every day is a series of cost/benefit decisions. I get one 45 minute planning period unmolested by meetings a day. Do I spend it in an IEP meeting that will surely go into my lunch break? Or do I use that time to provide written feedback on student writing? But if I do either of those, I won’t be able to finally meet with that student who has been writing about how bad his depression has gotten. I also need to check in with the counselor about a student’s math placement and think ahead to tomorrow’s lesson. Few of my options deal directly with classroom instruction and the Herculean task of growing readers and writers. So I understand why asking teachers to begin writing with their students seems like just another task.

But that the decision to write alongside our students isn’t a binary choice. It’s more of a stance we take towards curriculum, instruction, and our place inbetween. A teacher as writer stance connects us with the art and science of writing in a way that no rubric or exemplar ever could. It’s the best way to learn that a piece of writing’s center of gravity changes multiple times throughout the writing process. Or that no matter how hard an author wrestles with a piece, sometimes it just doesn’t work out.

To get started, consider one place you can write with your students. A brainstorming session for an upcoming essay or poem, for instance. The good thing about students not being used to their teachers writing is that they won’t call you out if you don’t follow through on it.

Writing alongside your students will fundamentally alter your relationship with what you teach, how you teach it, and how you relate to students. And as this relationship begins to shift, so will your relationship to the writing instruction that’s going on around you. You will (re)connect with the transformative potential of literacy and the power of words to bind us together. It’s a way to come home to a profession that seems so bent on throwing up hurdles between what we do and why we do it.

Conferring with Writers

Whenever I plan for writing conferences, my mind conjures up images of a Nancy Atwellian wonderland. Students laugh as we share humorous anecdotes about writing and life. Kids lounge on lush carpeting, lost in the pleasure of working on their pieces as they patiently wait their turn. Every student is smiling and every pencil is writing.

In reality, conferring with students about their writing is one of the most challenging things I do as an educator. My overstuffed classroom is filled with kids who scrape out two sentences a week jostling elbows with future Jason Reynoldses and J.K. Rowlingses. Also, the recursive nature of writing is at odds with the linear logic of most unit planning, so managing conference time within an at least semi-coherent sequence of planning, drafting, and revising. And any time I feel like I’m getting into the flow of it, a picture day/assembly/drill/band concert barges in.

On top of this, most kids come to the classroom convinced that writing is boring. That it’s a useless regurgitation of opinions and stories long calcified in their brains. Where’s the rubric? How many pages do I have to write? How can I get an A? I don’t fault them for this. It’s a logical response and it’s how you play the game of school.

When I do manage to make writing conferences work, it’s glorious. My approach to writing conferences aims for a middle ground blending a contemporary skills based approach with classic expressivism.

Peter Elbow’s 1973 classic Writing Without Teachers argues that when it comes to responding to student writing, traditional teachers are the worst. Elbow says that students need feedback that comes from readers, not teachers. Readers approach a text for pleasure and meaning. What effect do the words have on them? What do they wish the author did more or less of? What questions does the text leave them with?

He contrasts this to the traditional teacher, someone who experiences the text through the fragmented lens of assessing discrete skills and hunting for errors. Does the story effectively use dialogue not at all, some of the time, or most of the time? Do the student’s word choices nearly meet, meet, or exceed the expectations?

I begin a conference by reading a student’s piece quietly out loud to them. I make sure to display genuine engagement with and wonder about each piece. This takes practice. It’s been essential to my pedagogical spirit to retrain myself to see student writing as something to be enjoyed versus something to be fixed. I interject anytime I see something that works. A funny piece of dialogue, and suspenseful ending, a strong vocabulary word. Anything that would be useful for the student to do more of. I look specifically for craft moves. Using figurative language, intentional organization, etc.

This is where I try to respond to the piece as a reader. I ask what’s gonna happen next. I tell them what I’m curious about as a reader. What questions I have and what the piece makes me think about and feel.

Then I leave the student with one specific thing to do. Sometimes it’s as simple as “keep writing!” Other times it’s more targeted. “It looks like you’re ready to turn those stage directions into punctuated dialogue! Why don’t you review the dialogue punctuation handout I gave you on Monday?” This is where the direct object of teaching comes in. I’m teaching the students to do something besides just increasing their composition fluency.

On the best of days I can meet with around five kids per 42 minute class. After class I write down what I saw in each kid’s draft and what I told them to do. I’ve tried various documentation methods and this is what works best for me. The process of documenting a conference as it’s happening slows me down too much and breaks up the flow.

Students tell me that conferences help them improve as writers more than anything else we do in class. I never get to meet with every student during each assignment, but I do my best. Just like teaching, conferences are a messy dialogue between teacher and student, a challenging process that requires time, engagement, and reflection. But the juice is always worth the squeeze.

Writing Alongside My Students

Jorge jiggled his knee as I read over his story, his anxiety palpable. “It’s just… I mean… I know there’s a lot,” he said as he raked his hand through his spiky hair for the third time in as many minutes. He was right. By the end of the first page I counted at least eight characters and four drastically different settings. For feedback, I told him two things. First, that as a reader I was having a hard time figuring out who to focus on. Then I told him to listen as I read his story back to him. Which part of his story excited him the most? He zeroed in on a character (Tommy and his magical Book of the Dead) and left the conference with a more manageable scope to his story.

The rest of last week’s story conferences proceeded along similar routes. Sometimes the feedback was easy: insert a piece of dialogue that foreshadows the character’s conflict. Other times, it wasn’t. Helping writers nurture their strengths is a complex constellation of skills that I will probably never master. Anytime I felt stymied, I reached for Angela Stockman‘s fantastic Talking with Writers 2018. Talking with Writers devotes a section to responding to common problems in student writing. The strategy I used with Jorge came from Stockman’s work.

The ease with which I was able to apply this type of “See X? Try Y!” logic to student writing took me by surprise. As a committed member of the Northern Virginia Writing Project, I’ve always advocated for the power of writing alongside my students. And, following the work of Paul Thomas, I’ve also labored to try and become a scholar of writing. I’ve pursued composition pedagogy and history, written blog posts, and lead in-service trainings about the importance of knowing your theory.

However it wasn’t my understanding of composition or my status as a writer that helped me help my students. At least, I don’t think it was. Framed by schooling’s twin ideologies of efficiency and outcomes, every conference was compact and results oriented. Here’s what I see; here’s where you need to go; here’s a strategy to get you there. Does being a teacher of writing who writes provide any sort of advantage in this situation? Is this even the question to ask?

Normally, if my students are writing, so am I. It’s become an important part of my practice. It reminds me that writing exists outside of high-stakes accountability and the testing trap. It shows me that writing cannot be contained by formulaic essay constructions or meaningless assignments. But this method of instruction takes time, a teacher’s most valued currency. Every minute I spend writing alongside students is a minute I don’t have to confer with them.

During this last realistic fiction unit I chose not to write with them. I went with the more common alternative: work on something at home and bring it in as an example. I had more time to meet with my students, but I also felt disconnected, like a detached head floating above my students.

The debate over how best to spend class time isn’t new. In 1990, Karen Jost set off a firestorm within the secondary Language Arts community by arguing that the cost of writing with students outweigh the benefits. Students are best served by a teacher who meets with them and provides feedback, not by a teacher who labors over their own manuscripts. Jost lists the dizzying array of duties administrators and families expect of secondary teachers. With this list in mind, it is hard to imagine how teachers can confer with students, give daily instruction, provide written feedback, attend school functions, etc. and still find the time to sit down and write.

Ideally, we would do both. We would workshop their pieces with our students, in the process modelling authentic purposes, purposeful revision, and the writing life. As we did this, we would confer with students and do our best to guide them through the infinite complexity of composition. But there is not enough time to do both.

There is no answer. Or if there is, I don’t know it. But I do know that what we do shows what we value. The pedagogies we enact are inextricably linked to who we are as teachers, writers, and professionals. We make sure to share our reading lives with students. We give book talks, do read alouds, and converse with our kids about the books that matter to us. Can we say the same about our lives as writers?

———————————————-

-Image credit: CC0 Photo by freestocks.org on Unsplash

“Have you READ their writing?” Resisting the Obsession with Mechanical Correctness

Listening to teachers complain about student writing is exhausting. They can’t write; they don’t know where to use commas; they don’t capitalize every i; their spelling is atrocious. When this sort of narrative pops up in mainstream discourse, it’s often to complain about education’s failure to prepare kids for the workforce and to provide a platform for ‘back in my day, teachers made us diagram sentences/memorize parts of speech/etc.’ bloviating.

When these sentiments appear inside a school, they take on a slightly different tenor. Behind every complaint about a kid’s writing seems to be an underlying message about the failure of that child’s previous language arts teacher(s). It’s as if the teacher is throwing their hands up and proclaiming ‘Look at the mess I inherited! What am I supposed to do? How can I teach my content when these kids don’t even understand the basics!’

There’s a lot to unpack here. First, this nagging is counterproductive and can build resentment among teachers. Schools have more than enough finger-pointing as it is; engaging in ego-driven grandstanding serves no one.

To the teachers who regularly engage in this sort of carping, please stop. If you don’t like what your students are producing, then address it in the classroom. Regardless of content or grade, helping children learn to read, write, speak, and think is everyone’s responsibility. These complaints also elevate surface features (spelling, grammar, basic syntax) above all else.

The notion that mechanical perfection is the goal of writing instruction is deleterious to good teaching. It reinforces a deficit view of student writing by focusing on what a child did wrong. It trains us to approach student writing as something to be endured, some sort of gauntlet all language arts teachers must go through. It also encourages teachers and students to see writing as a series of levels to be mastered. Writing doesn’t care about scope and sequence documents or district-wide vertical alignment. It grows in fits and starts, evolving through recursive spirals of progress and regress.

Historically, evidence shows that teachers have been complaining about student writing since the first American universities. In The Rise and Fall of English, Robert Scholes examines primary documents such as university syllabi and commencement speeches to conclude that

English teachers have not found any method to ensure that graduates of their courses would use what were considered to be correct grammar and spelling. A number of conclusions can be drawn from this situation. One is that the good old days when students wrote “correctly” never existed. A second conclusion might well be that two hundred years of failure are sufficient to demonstrate that what Bronson called beggarly matters (spelling, grammar, capitalization, punctuation) are both impossible to teach and not really necessary for success in life. (p. 6)

This isn’t all to say that mechanical correctness doesn’t matter. The above notion that grammar and spelling are not “necessary for success in life” should be followed by “for certain people.” I’m reminded of an anecdote from Christopher Emdin’s For White Folks Who Teach in the Hood. Emdin recounts a conversation with a white teacher about the role of appearance. The teacher doesn’t understand why her students of color seem so focused on fashion and style. What do these things matter? After all, she says, she comes to school every morning in casual dress. Emdin replies that the ability to be treated professionally regardless of dress is a luxury many people of color can’t necessarily afford.

So of course grammar and spelling matter. Certain errors like nonstandard verb forms and incorrect subject/verb agreement can carry serious connotations of race and class. The legacy of mechanical correctness is steeped in racism, xenophobia, and class anxiety (for more on this, check out Mechanical Correctness and Ritual in the Late Nineteenth-Century Composition Classroom by Richard Boyd and The Evolution of Nineteenth-Century Grammar Teaching by William Woods). As teachers, we have the responsibility to help students understand the intersections of power and literacy. But this doesn’t mean chastising students for every mistake they make in their writing. Nor does it mean requiring every student draft to be mechanically perfect.

My go-to authority for how to treat errors in student writing is Constance Weaver. She urges us to see errors as a necessary component of growth. The following chart, taken from her Teaching Grammar in Context, sums up what a more compassionate and purposeful approach towards errors might look like.

Along with the solid tips outlined above, remember that students should focus on superficial edits using their own writing, on a topic they care about, during the final stages of the writing process.

If nothing else, stop complaining about student writing. It’s counter-productive to our mission and makes an already exhausting job that much more draining. If you’re not enjoying yourself, neither are they.

Making Family Dialogue Journals Work

A little over a year ago I first wrote about family dialogue journals (FDJs). An FDJ is a notebook that travels between a student’s home and classroom. Teacher, child, and family member use the journal to engage in a written dialogue about curriculum, traditions, family history, etc. I decided to try FDJs out as a way to keep families informed of what was going on in their child’s English class. My first year using them was neither a success nor a failure. It was, however, a lot of work. I spent the year haranguing children to return their journals and lugging around tote-bags of notebooks so I could scratch out personalized FDJ responses during any spare moment.

So when it came time to map out my 2016-17 school year, I didn’t know if I had it in me to continue. This changed when I connected with Kathleen Sokolowski over at Two Writing Teachers in August. A Voxer conversation that started with a discussion of removing grades from the classroom turned into an extended back and forth about family dialogue journals. Kathleen decided to give FDJs a shot (check out her excellent post on the subject over at Two Writing Teachers). Her enthusiasm reignited my commitment. I wrote an FDJs Revisited post, cleared away any mental detritus, and prepared to try again in September.

It’s now November; my 7th graders have completed four rounds of FDJing. This year’s crop of students seem more amenable to the FDJ concept than last year’s. They brought in their notebook at the beginning of the year (without any nagging on my end. They’ve also been more apt to speak openly about their families and non-school lives.

Instead of asking students to read their FDJs in entirety in front of the class as I did at the beginning of last year (wince), I’ve asked students to share sections of their family’s responses in small groups. I’ve also given students the option to share a different piece of writing if they wish. This way everyone has something to read. Kids who don’t have their FDJs or don’t feel comfortable sharing them for whatever reason can still participate. These small tweaks, combined with the aforementioned shift in classroom attitude, have resulted in a much friendlier environment for sharing. What follows is a slightly more in-depth look into how I’ve been approaching Family Dialogue Journals this quarter.

Every other Friday is a designated FDJ day. By the time Friday rolls around I’ve managed to respond to every journal I’ve received over the two week period. Below are two random examples of my responses. As you can see, they’re not great. Sometimes the parent gives me something to work with, and often they don’t. But writing these replies is a two-way street, and I’m just as responsible for crafting interesting responses as families are. Probably more so, in fact. Right now as long as I’m replying to one specific thing from each FDJ entry I’m satisfied. Writing 60+ personalized responses (while not every student brings them in, this is almost a 100% increase in participation from this time last year) requires me to straddle the line between making it meaningful and getting it finished. Part of me relishes this challenge since figuring out that balance seems to be a crucial aspect of life.

I mentally divide FDJ day into two chunks: sharing last week’s response and writing next week’s letter. Instead of taking part in our normal class openers (we alternate between independent reading and notebook time), I ask students to find something to share with their group. If they have their FDJs they read their family’s most recent response and select up to four sentences to share. I’ve learned that students need these few minutes in order to decipher handwriting, mentally prepare to read out loud, and figure out what they want to share.

When everyone is ready, I kick things off by reading my own family’s response. Last year my mom was kind enough to write back and forth with me, and this year my dad has taken over the duty. Once I read my dad’s response I have a few students share connections, summarize, etc with what I read. I expect students to do this for each other, so getting everyone warmed up with my own FDJ works well. Then it’s their turn. Every group of four reads to one another using the following protocol:

This protocol helps group members stay involved by requiring them to respond in a particular way (I enjoy thinking protocols. The National School Reform Faculty’s website has a ton of good ones). I do my best to stay on the sidelines during this time, planting myself in the middle of the room and dividing my attention between every group.

After everyone has shared, we get ready to write our next letters home. Although I change the exact mechanics each time, I like to make sure the students talk before they write. Sometimes we use chalk talk activities where students move silently throughout the room and reflect on the last two weeks’ worth of instruction. Last time I sorted everything we’d done into four categories (see below).

Then students picked the category they wanted to write about and met up with other students interested in the same topic. The goal is to help each child come to the page ready with some ideas. Once we’ve brainstormed and bounced ideas off of one another, it’s time to write.

I show them the next letter I’ll send to my dad. I like to color code my writing; it helps me highlight the different elements I want the students to include.

A much better way to do this would be to engage students in some type of letter genre study. What common elements can we find in typical letters? What kind of information do authors include? How do they convey that information? What purposes do we write letters for? etc. But I’m approaching FDJs in baby steps, and what we’re doing now gets the job done.

What students choose to say about class and what they’ve been doing is always illuminating.

Students end their letters by coming up with a question to ask someone at home. Ideally every child’s question relates to what we’re studying in class. Right now, however, I’m pretty much giving them free reign over what they ask. By the time students finish writing their letters the class period is just about over. The process ends when I send out an email reminder to parents that afternoon (the first of three reminder emails per cycle).

So far the FDJs are mainly functioning as a form of increased school-family communication. This is the most basic of purposes. My next goal is to use the family dialogue journal to engage parents with questions related to the content of the course. By the time I write my next FDJ post in a couple months I’ll hopefully be able to speak on using the FDJ as a instructional resource.

How do you communicate with families? What methods do you use beyond report cards and signed quizzes/tests?

Beyond Socratic Seminars and Essential Questions: The Importance of Student Generated Questions – NVWP Summer ISI – Day 14

Welcome to the Northern Virginia Writing Project’s 2016 Invitational Summer Institute! I’ll be blogging the demonstration lessons and the various activities occurring during our four-week duration. Find out more about the NVWP and the National Writing Project.

Today’s second presentation comes from Steph Lima. It explains how to use student-centered questions in the classroom.

Quickwrite: Write about your successes and challenges with either small and / or large group discussions.

Oh, boy. Discussion is something that I really need to work on. I’m acceptable at it, but nowhere near great. Right now I can only think of my deficits in this area. I need to work on finding the right balance of creating guiding questions and having a direction in mind vs. allowing a discussion to grow organic legs that allow it to move wherever. I know that it helps to write out a few sequenced questions before hand, to frame questions in affective ways, to begin with real-life scenarios, and to summarize/paraphrase student responses, and to help connect students to each other during the discussion. Perhaps some of my weakness comes from my fear of sustaining a whole class discussion for any length of time. I’m always so afraid children will get squirrely and bored and that the introverts will disappear.

We share out. Someone talks about how their own school experiences played a role in this. This gets me thinking. It’s hard for me to remember a time when I felt confident participating in a large scale conversation. This also relates to a larger feeling of alienation that I experience whenever talking about academic/intellectual things.

Stephanie tells us about the origin of her presentation. She was unsatisfied with the quality of student discourse, and she felt she was enabling it. Heads are nodding. She decided to revamp how she approached class discussion. She divided questions into three types:

She spent time with students going over questions, writing them, and categorizing questions that students brought in. This reminds me of the importance, again, of modeling and teaching the academic moves we expect children to do. Asking questions and conversing is actually a complex skill, one that requires multiple layers of cognition.

After students brought in their self-generated questions, they took turns passing them around, reading each other’s questions, and annotating. Then Steph had the students pick a few questions that weren’t theirs to answer in writing. Students then picked one of their answers to discuss with the small group. Then, after that, she opened it up to the whole class. By talking it out in small groups first, every student went into the whole-group with a variety of talking points. The power of constructivism!

Now it’s our turn. Steph passes out copies of “The School Children” by Louis Gluck. She says it offers a rich variety of analyses.

We read twice and then annotate for whatever we notice. Next we write as many questions as we can, keeping the previous levels in mind. After that we write our best two on sticky notes and put them in a pool on our group’s table. We pick two (that aren’t ours!) and then write answers to them. No one is speaking yet. After writing, then we begin sharing out our questions and answers with our group members. Holy smokes this poem is amazing!

This reminds me of a) the value of writing before discussing and b) how this sort of ‘write questions – put them in the center for everyone’ technique can be way more useful than ‘everyone look at each other and brainstorm out loud.’ This way there’s less pressure and I can come up with ideas at my own pace and even pick out from among my ideas the best ones to share out. Each group discusses. Zone of Proximal Development in full effect!

We share out. Many of us cry out to hear what the poem is “about.” Steph wisely stays mum on the subject. We often tell children “it’s not about the answer.” We must resist this temptation ourselves. Steph ends by telling us she has the kids write about and reflect on why they chose the questions they did, and etc. This approach was way more generative than her previous discussion techniques.

I cannot WAIT to do this next school year.

Harnessing the Power of Purpose and Audience: Authentic Writing in the Classroom – NVWP Summer ISI – Day 14

Welcome to the Northern Virginia Writing Project’s 2016 Invitational Summer Institute! I’ll be blogging the demonstration lessons and the various activities occurring during our four-week duration. Find out more about the NVWP and the National Writing Project.

Our final day of presentations begins with Sara Watkins talking to us about how she uses authentic writing in her high school classroom.

Quickwrite: Think about a writing assignment you’ve given that your students enjoyed. Describe the lesson: what was it? What was its purpose? Who was the audience for the students?

Towards the end of the year I ran the students through a Flash Fiction mini-unit. We read examples, took them apart to see what made them tick, and tried to figure out what the genre was all about. Students then created their own examples of Flash Fiction. I had them concentrate on conflict types, economy of language, and otherwise following the genre rules we discussed. I wanted the students to gain practice with honing in on various conflict types, working through plot elements, and figuring out how to say a lot with a few amount of words. The audience, unfortunately, was just the class. By the end of the year students knew that pretty much anything they wrote would be put up on the walls to be read and discussed with classmates.

BTW, authentic writing is pretty much any genre of writing that is “found in the real world” and written for an audience outside of the school. Authentic writing creates links to the community. Writing for an authentic audience helps children believe in the power of their own voice and their own story. Here are some examples of genres of writing used by non-teachers:

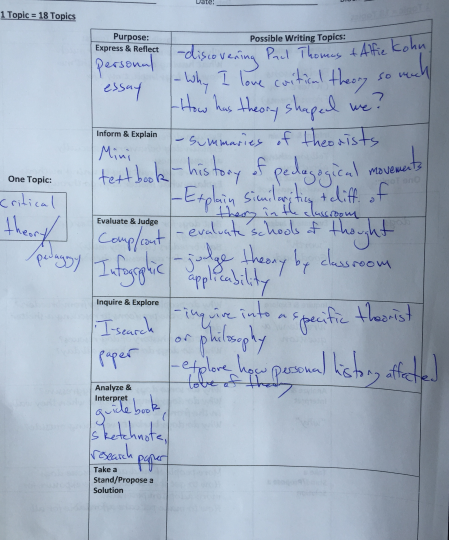

Sara passes out a Kelly Gallagher sheet on approaching one topic in 18 different ways. The left hand column represents six prominent purposes available for a topic. The right hand column offers some guidance on how to get started with each purpose.

Sara shows us a model of her own writing. She splits her favorite topic (dogs!) into the six purposes. Each purpose contains at least three topics about dogs. Yet another successful example of the basic guided release model (teacher walks the class through an already completed/in process example to show basically show students what to do. Then students are encouraged to do their own). Now it’s our turn to do the same! Here’s my example. I didn’t finish it in time. Sorry about the poor lighting.

We share out. It’s amazing what a wealth of information can come from just a single topic! Even if some of my/out ideas don’t fit squarely into each category, that doesn’t matter. What matters is generating tons of student-centered ideas from a single student-centered topic. The classroom is crackling with ideas and laughter.

I can’t wait to use this in my class this year. She ends up with a list of resources.