Category: Assessment

“This Class is Easy” Some Minor Thoughts on Rigor in the Gradeless Classroom

I hate grading things. I have a lot of students and it takes too long and it doesn’t increase anyone’s ability to read, write, speak, or think critically. So I don’t do it. I haven’t done it in five years. Since my district requires a letter at the end of every quarter, students assign themselves a grade as part of their quarterly portfolios.

Most kids give themselves B’s. No one wants a C because that makes honor roll impossible. Families often hitch rewards and punishments to report cards. Other students are nervous about giving themselves an A because they think I’ll challenge it. Rarely do I give out anything lower than a C. First, it feels icky to go nine weeks without mentioning grades and then suddenly become tyrannical about them. Kids would feel sucker punched.

Second, low grades also don’t increase student learning. Kids who aren’t turning in assignments or engaging with the content aren’t doing so because I haven’t dangled enough carrots from the stick. Everyone wants to do well and find success. Students struggling with this need things like strategies, compassion, consistency, and support. Not grade shaming.

Don’t misunderstand me. High expectations can and should exist without grades. I’ve found that maintaining the expectation of excellence is harder to do in the gradeless classroom. This comes from students telling me that my class is easy. They say the lack of grades lowers their anxiety. They don’t have to cram for unit tests or drill Kahoots to memorize terms.

That makes sense. We tend to equate intellectual rigor as something that can only happen if a student is stressed out and anxious. Something is only hard if it threatens our grades. This is a totally rational response to a system that prizes extrinsic rewards above anything else.

My ability to engage students without relying on grade-related threats will probably always be a struggle. It’s a Sisyphean goal. Yes, I work to cultivate meaningful relationships and build a classroom environment that fosters intellectual risk taking. I try to locate authentic audiences for student work and articulate clear purposes for every assignment. But at the end of the day, not everything can be fun and work stinks.

Grades aren’t going anywhere. They’re too baked into the system. There’s no way to move massive numbers of students up and down grades and in and out of different schools without some sort of standardized reporting. The inertia behind standard grade reporting feels insurmountable. Besides, there are more pressing issues to focus on such as educational inequity and structural racism. While grades can be understood as a manifestation of oppressive assessment systems, a focus on removing grades can easily miss the forest for the trees.

I don’t plan on returning to grades. It’s on me to engage students through my curriculum and instruction while leveraging as little extrinsic motivation as possible. If students are only working for the grade, then I haven’t done my job. That’s my favorite part about going gradeless. It forces me to fight for my subject matter and my discipline. I get to spend every day making the case for why this stuff matters.

Conferring with Writers

Whenever I plan for writing conferences, my mind conjures up images of a Nancy Atwellian wonderland. Students laugh as we share humorous anecdotes about writing and life. Kids lounge on lush carpeting, lost in the pleasure of working on their pieces as they patiently wait their turn. Every student is smiling and every pencil is writing.

In reality, conferring with students about their writing is one of the most challenging things I do as an educator. My overstuffed classroom is filled with kids who scrape out two sentences a week jostling elbows with future Jason Reynoldses and J.K. Rowlingses. Also, the recursive nature of writing is at odds with the linear logic of most unit planning, so managing conference time within an at least semi-coherent sequence of planning, drafting, and revising. And any time I feel like I’m getting into the flow of it, a picture day/assembly/drill/band concert barges in.

On top of this, most kids come to the classroom convinced that writing is boring. That it’s a useless regurgitation of opinions and stories long calcified in their brains. Where’s the rubric? How many pages do I have to write? How can I get an A? I don’t fault them for this. It’s a logical response and it’s how you play the game of school.

When I do manage to make writing conferences work, it’s glorious. My approach to writing conferences aims for a middle ground blending a contemporary skills based approach with classic expressivism.

Peter Elbow’s 1973 classic Writing Without Teachers argues that when it comes to responding to student writing, traditional teachers are the worst. Elbow says that students need feedback that comes from readers, not teachers. Readers approach a text for pleasure and meaning. What effect do the words have on them? What do they wish the author did more or less of? What questions does the text leave them with?

He contrasts this to the traditional teacher, someone who experiences the text through the fragmented lens of assessing discrete skills and hunting for errors. Does the story effectively use dialogue not at all, some of the time, or most of the time? Do the student’s word choices nearly meet, meet, or exceed the expectations?

I begin a conference by reading a student’s piece quietly out loud to them. I make sure to display genuine engagement with and wonder about each piece. This takes practice. It’s been essential to my pedagogical spirit to retrain myself to see student writing as something to be enjoyed versus something to be fixed. I interject anytime I see something that works. A funny piece of dialogue, and suspenseful ending, a strong vocabulary word. Anything that would be useful for the student to do more of. I look specifically for craft moves. Using figurative language, intentional organization, etc.

This is where I try to respond to the piece as a reader. I ask what’s gonna happen next. I tell them what I’m curious about as a reader. What questions I have and what the piece makes me think about and feel.

Then I leave the student with one specific thing to do. Sometimes it’s as simple as “keep writing!” Other times it’s more targeted. “It looks like you’re ready to turn those stage directions into punctuated dialogue! Why don’t you review the dialogue punctuation handout I gave you on Monday?” This is where the direct object of teaching comes in. I’m teaching the students to do something besides just increasing their composition fluency.

On the best of days I can meet with around five kids per 42 minute class. After class I write down what I saw in each kid’s draft and what I told them to do. I’ve tried various documentation methods and this is what works best for me. The process of documenting a conference as it’s happening slows me down too much and breaks up the flow.

Students tell me that conferences help them improve as writers more than anything else we do in class. I never get to meet with every student during each assignment, but I do my best. Just like teaching, conferences are a messy dialogue between teacher and student, a challenging process that requires time, engagement, and reflection. But the juice is always worth the squeeze.

The Limits of Community and the Future of Going Gradeless

This is the second in a series of posts exploring teaching and learning in the de-graded and de-tested language arts classroom. Read the first post here.

The Limits of Community and the Future of Going Gradeless

Teaching can be a lonely profession. Even though I come into contact with 120 people every day, most of the interactions are asynchronous. The relationships I have with my students are authentic, and I do my best to build reciprocity and trust, but I’m in a different place than them. -To restrict our focus to matters of measurement is to miss an opportunity not just to reimagine education, but to reimagine our place within education. o circumscribed by centuries of hierarchical teacher/student dynamics. On the other hand, my peers and I are on equal footing. But the demands of the job keep a tight leash on what we talk about and when we talk about it. When I meet with my fellow 7th grade English teachers, for instance, we’re expected to follow the district’s meeting template. And when it comes to instruction, the three of us are expected to maintain a certain level of consistency in what we teach and how we assess it. This creates a fixed community, a group of teachers bound by shared purpose, goals, and ideally beliefs.

My coteaching community hummed along until I started changing my beliefs about grades. As soon as I started questioning the role I wanted grades to play in my classroom, I began drifting away from the group. Every question I raised about the purpose of our common assignments sent me farther away from my coworkers. The disintegrating kinship I was experiencing had little to do with conflicts of personality or a lack of professionalism. A series of systems all pointing in the same direction can’t accommodate someone being at cross purposes with the flow. I wasn’t a wrench in the system, just an outcast.

Our biweekly meetings stopped being productive. The three of us came to an unspoken agreement that our time together would be spent on filling out IB unit planners for units we would never teach. The unwieldy and overly complex unit template made it easy to spend 45 minutes working on it without actually accomplishing anything. The unit planners became a way to keep up the facade of being on the same page. By the end of the year, the assistant principal was in every meeting to help make sure we were creating common assessments and focusing on similar skills. The situation wasn’t anyone in particular’s fault; none of us wanted to compromise. I was alone, a prisoner of my dogmatic beliefs.

PLNs, Social Media, and Belonging

Fortunately, the demise of my coteacher community was offset by the discovery of an online network of like-minded educators. Frustrated at having no one to talk to, I began reaching out to the academics I’d been reading: Paul Thomas, Alfie Kohn, Maja Wilson, and Lawrence Baines. I asked all of them if they had ever found themselves on the wrong side of their respective communities. Much to my surprise, each of them responded. It was like shouting into the void and receiving an invitation to a secret club filled with the coolest and smartest people ever. Kohn’s response has stuck with me. With his permission, I’ve reprinted it below.

I can certainly sympathize; taking unpopular stands has a way of making folks, well, unpopular. Naturally it helps to find a kindred spirit if there’s one in your area. Otherwise you have to decide whether to reach out to others — perhaps by sharing books, articles, and videos — in the hope of persuading some of your colleagues to question the conventional wisdom and thereby *creating* some kindred spirits to connect with.

The alternative is to push on alone and connect with colleagues around other stuff so you don’t feel completely isolated. How best to proselytize, or to sustain friendships in spite of divergent views, depends on your personality and values, their personalities and values, and various details of the situation in which you find yourself — all matters on which I can’t advise you, of course.

Taking his advice, I decided to search for kindred spirits on Twitter and Facebook. My first discovery was the Teachers Throwing Out Grades community. I was surprised to see a lot of resources about standards-based grading, proficiency scales, and single-point rubrics. All of the talk seemed to revolve around perfecting the measuring of student learning. For me, this is the least interesting part of education. My brain recoils the second I ask it to focus on learning outcomes or to disaggregate state standards. Rather than offering me a safe space to connect with others, the TTOG community kept my attention trained on the very thing I was escaping. On top of this, a few big names seemed to dominate the discussions. I couldn’t escape the feeling that the group was little more than a chance for the big name members to push their books, consulting services, and brands. I lurked for awhile, but I knew I had to keep looking.

Around this time I attended a standards-based grading seminar led by the outstanding Rick Wormeli. I was ecstatic. These could be my people! Indeed, many of Rick’s points, such as eliminating zeroes, questioning the efficacy of homework, and allowing for retakes, fit easily into the definition of teaching and learning I was developing. I knew by the end of the seminar, however, that the SBG community wasn’t for me. Standards-based grading’s emphasis on content mastery and tracking student progress of state standards was a turn-off. So was what I felt to be an obsession with self-assessment. I value self-reflection, and I spend considerable time every year working with students to build their capacity to accurately and honestly evaluate their work. But I’m not interested in linking their self-reflections to rubrics or asking them to rate themselves. To me, this is another example of the managerialism that I’m trying to avoid. There’s nothing particularly interesting or liberatory in asking students to pick apart everything they do, and the majority of self-assessment practices I read about strike me as extensions of the teacher-led grading.

Becoming Something More

I gave up actively searching for a community that would support who I was becoming as a teacher. Anything that dealt with the removal of grades seemed to focus on other stratified systems of measurement. And websites and Facebook groups devoted to pedagogy and improving instruction always discussed traditional grades. So when my colleague Arthur Chiaravalli told me he was forming a new group with Aaron Blackwelder devoted to teachers going gradeless, I was hesitant. Once the Facebook posts and blog pieces started flowing, I started disengaging. It was just too much. Don’t misunderstand me; the quality of the posts and the nature of the questions were fantastic. I just don’t want to talk about grades. That’s why I stopped using them. I’m done with them. Nor do I care about what to use in place of grades. The whole situation can lead me to endlessly compare myself to others, too, a sort of meta-commentary about grades and competition and our culture’s relentless drive to be the best.

Students should be receiving feedback from teachers and peers. It should help students see what they’ve done well (so they can keep doing it) and what they can improve. As far as I’m concerned, that’s the extent of it. Lots of feedback given by lots of people combined with lots of chances for revision. Feedback comes in many forms, and it’s important to find a method that works, but I think something valuable is lost when a community does nothing but showcase different systems of measurement.

In my own practice, removing grades has given me the opportunity to focus on the stuff that I think matters: building relationships, creating meaningful lessons, and providing a safe space for students to stretch, fail, and grow. For me, this is the work of teaching. This is what I want to talk about and puzzle through. To that end, the gradeless community can function more as a station than a destination, a launching pad for educators to come together before heading off on their own individual paths. The topic of removing grades also feeds into many of the education issues of our time: personalized learning, ESSA, equity, and policy.

I can feel my desire to align with Teachers Going Gradeless and to place the corresponding hashtags on my social media bios. But at the same time, I’m wary of becoming entrenched in any one community. This has more to do with the idiosyncrasies of my personality than it does TG2 (or any community). The relentless drive to connect my heart with my instruction is restless. Perhaps it sees within any community the threat of calcification and the gravity of consensus. I remain confident, however, that restricting our focus to matters of measurement misses an opportunity to rebuild and reimagine who we are as educators.

To Change Everything While Changing Nothing: Going Gradeless

This is the first in a series of posts exploring teaching and learning in the de-graded and de-tested language arts classroom.

The first thing I tell teachers about removing grades is that it changes everything while simultaneously changing nothing. Students still come to class, complete assignments, and receive feedback. Hyper-students, kids who have successfully mastered the convergent thinking and mimicry of traditional schooling, continue their institutionally and culturally-sanctioned quest to acquire as many points as possible. Students who struggle to play along with the game of school’s idiosyncratic and often artificial demands continue to struggle. Students might report an atmosphere of reduced classroom pressure, but for the most part everything functions as it always has.

From my perspective, the decision to remove grades, quizzes, and tests led to two major changes in how I operate as a teacher. First, I had to learn to manage student behavior without using grades as leverage. No longer could I “remind” a disengaged student that the end of the quarter was coming up and that their parents were expecting honor roll. Without that leverage, I was forced to rethink every assignment. Each lesson needed to serve a specific purpose, something larger than the acquisition or maintenance of a number. This was the second shift. I needed to be able to articulate a convincing and meaningful answer to the ubiquitous student question of “Why do I have to do this?” Authentic learning and grades aren’t mutually exclusive, but the absence of the latter heightens the teacher’s responsibility to foster the former.

The first time I told my students I would no longer be grading any of their assignments, it did not go as I had planned. In my mind, I expected to be greeted as a hero, a classroom revolutionary fighting against punitive systems of assessment. Having just read books and articles by Alfie Kohn, Mark Barnes, and Paul Thomas, I delivered a sermon to my first period class on the tyranny of numbers and letters. No longer would students need to worry about the pressures of report cards or quarterly honor roll lists. Beaming, I faced my students, eager to celebrate what was sure to be a new era of unencumbered learning and intellectual freedom.

Instead, I was greeted by blank stares and barely contained rage.

Some students stood up from their desks and berated me, their small hands balled up at their sides. Others glanced at each other and exchanged looks of “This guy can’t be serious.” Most students, however, responded with indifference. At the time, I didn’t understand. Everything I had read about de-grading the classroom stressed the importance of transparency. Of speaking with your students about what you’re doing and why you’re doing it. Yet the more I tried to explain myself, the more upset students seemed to become. Stumbling over my words, I attempted to mollify the room by explaining how everyone would be responsible for coming up with their own grade. This didn’t help. Grades rewarded good behavior, many protested, and allowing the kid who rarely turned in work to end up with the same grade as the student who dutifully completed every assignment was unfair. The picture at the top of this piece comes from one such student.

Looking back, I now realize I was experiencing what Paul Thomas described as students’ disconnect between “their behavior as students as opposed to learners” (246). By removing the dominant motivator and purpose of school without warning, many students understandably felt cheated and betrayed. I had done little to foster dialogue around issues of assessment and equity with my classes. If anything, I had gone in the opposite direction; I just wanted everyone to think exactly like I did, an irony lost on me at the time. Rather than encouraging students to discuss issues of assessment, grades, and equity, I was attempting to indoctrinate them with my own ideology. Despite the rocky start, I was able to stumble through my attempts at quarterly portfolios and individual grade conferences.

I took a similar approach with my administration. I decided to wait until I had removed every possible grade, quiz, and test from my classroom before bringing it up to my evaluator, one of the assistant principals. I was terrified. I had no clue what I was doing, and I didn’t want to derail the process before I was able to work some things out for myself. The day I introduced the first quarterly portfolio assessment to the students was also the day I revealed everything to my administration. That morning before classes had started, I shuffled into my administrator’s office. Eyes glued to the carpet, I unloaded a stream of consciousness speech about everything I had been doing. As penance, I begged him to come and observe my portfolio roll-out. He didn’t say yes, but he didn’t say no, either.

With most of my students and administrators cautiously on board, I was set. As the weeks went by, I realized what Paul Thomas meant when he wrote, “Non-traditional practices in any classroom make direct and indirect commentaries on other classrooms, the practices in those classrooms, and the teachers/professors leading those classrooms” (248). Over time, I came to feel like the entire school building was against me. Honor roll lists and admonitions to “do your best on the test!” plastered the halls. Students were routinely told that school was their job and that grades were their paycheck. Parent-teacher conferences were shackled by a language of learning that emphasized measurable progress and little else.

I became known as the easy teacher among some students and even a few colleagues. I don’t blame them. As Karen Surman Paley writes, “Any pedagogy that results in grading students, ranking them in their class, and providing the basis for records…is part of capitalist relations of power and authority” (26). Without points to fight for and assignments to dominate, it’s easy to paint my class as “soft.” I’ve come to accept that regardless of how hard I push my students to read, write, think, and speak critically, a certain segment of the school population will always think my class is easy because students don’t receive marks.

My district does, however, require me to input at least one grade for every quarter. I’ve handled this a few different ways. For instance, students and I have worked together to create criteria that they use to assess themselves during the portfolio process. Most students give themselves B’s. Anything higher risks extra teacher scrutiny, while anything lower has the possibility to cause parental strife. I’ve also tried limiting final grades to only A’s, B’s, and C’s. Most recently, I’ve experimented with giving everyone an A. The less thought I devote to parsing out who deserves what, the more time I can devote to planning meaningful lessons and providing effective feedback.

Now, the only time I discuss my grading policy with students and parents is during back to school night. I explain to families that their students won’t be taking any quizzes or tests, but that they will receive constant feedback about their performance. I hold up a couple of old student portfolios, go over feedback protocols, and try to do everything I can to convince families that their children are in good hands. The only question that continues to stump me is when parents ask how they’ll be able to stay on top of their child’s performance. I have a difficult time answering this question without launching into a diatribe about how traditional grades offer only an illusion of reporting. I want to ask families if they interrogate quiz and test grades with the same level of skepticism. But this is only because I’m self-conscious about my inability to provide a clear and direct answer to the essential and timeless question of “How will I know how my child is doing?” Since dropping grades, I’ve implemented assignments such as Family Dialogue Journals to try and keep parents informed of what’s happening in the classroom, but the situation remains far from perfect. Like everything else, this is a process, and I’m in it for the long haul.

“Have you READ their writing?” Resisting the Obsession with Mechanical Correctness

Listening to teachers complain about student writing is exhausting. They can’t write; they don’t know where to use commas; they don’t capitalize every i; their spelling is atrocious. When this sort of narrative pops up in mainstream discourse, it’s often to complain about education’s failure to prepare kids for the workforce and to provide a platform for ‘back in my day, teachers made us diagram sentences/memorize parts of speech/etc.’ bloviating.

When these sentiments appear inside a school, they take on a slightly different tenor. Behind every complaint about a kid’s writing seems to be an underlying message about the failure of that child’s previous language arts teacher(s). It’s as if the teacher is throwing their hands up and proclaiming ‘Look at the mess I inherited! What am I supposed to do? How can I teach my content when these kids don’t even understand the basics!’

There’s a lot to unpack here. First, this nagging is counterproductive and can build resentment among teachers. Schools have more than enough finger-pointing as it is; engaging in ego-driven grandstanding serves no one.

To the teachers who regularly engage in this sort of carping, please stop. If you don’t like what your students are producing, then address it in the classroom. Regardless of content or grade, helping children learn to read, write, speak, and think is everyone’s responsibility. These complaints also elevate surface features (spelling, grammar, basic syntax) above all else.

The notion that mechanical perfection is the goal of writing instruction is deleterious to good teaching. It reinforces a deficit view of student writing by focusing on what a child did wrong. It trains us to approach student writing as something to be endured, some sort of gauntlet all language arts teachers must go through. It also encourages teachers and students to see writing as a series of levels to be mastered. Writing doesn’t care about scope and sequence documents or district-wide vertical alignment. It grows in fits and starts, evolving through recursive spirals of progress and regress.

Historically, evidence shows that teachers have been complaining about student writing since the first American universities. In The Rise and Fall of English, Robert Scholes examines primary documents such as university syllabi and commencement speeches to conclude that

English teachers have not found any method to ensure that graduates of their courses would use what were considered to be correct grammar and spelling. A number of conclusions can be drawn from this situation. One is that the good old days when students wrote “correctly” never existed. A second conclusion might well be that two hundred years of failure are sufficient to demonstrate that what Bronson called beggarly matters (spelling, grammar, capitalization, punctuation) are both impossible to teach and not really necessary for success in life. (p. 6)

This isn’t all to say that mechanical correctness doesn’t matter. The above notion that grammar and spelling are not “necessary for success in life” should be followed by “for certain people.” I’m reminded of an anecdote from Christopher Emdin’s For White Folks Who Teach in the Hood. Emdin recounts a conversation with a white teacher about the role of appearance. The teacher doesn’t understand why her students of color seem so focused on fashion and style. What do these things matter? After all, she says, she comes to school every morning in casual dress. Emdin replies that the ability to be treated professionally regardless of dress is a luxury many people of color can’t necessarily afford.

So of course grammar and spelling matter. Certain errors like nonstandard verb forms and incorrect subject/verb agreement can carry serious connotations of race and class. The legacy of mechanical correctness is steeped in racism, xenophobia, and class anxiety (for more on this, check out Mechanical Correctness and Ritual in the Late Nineteenth-Century Composition Classroom by Richard Boyd and The Evolution of Nineteenth-Century Grammar Teaching by William Woods). As teachers, we have the responsibility to help students understand the intersections of power and literacy. But this doesn’t mean chastising students for every mistake they make in their writing. Nor does it mean requiring every student draft to be mechanically perfect.

My go-to authority for how to treat errors in student writing is Constance Weaver. She urges us to see errors as a necessary component of growth. The following chart, taken from her Teaching Grammar in Context, sums up what a more compassionate and purposeful approach towards errors might look like.

Along with the solid tips outlined above, remember that students should focus on superficial edits using their own writing, on a topic they care about, during the final stages of the writing process.

If nothing else, stop complaining about student writing. It’s counter-productive to our mission and makes an already exhausting job that much more draining. If you’re not enjoying yourself, neither are they.

So What Do You Do?

At a recent department meeting, the call came down for every teacher to produce spreadsheets for the data from our most recent district-mandated benchmark exam. We were to chart out student performance by standard, strand, score, and subgroup. This request is nothing new. Administrators have been asking for charts, and teachers have been making them, since at least the nineteenth-century*. Even without the marching orders, many of us would continue to make such spreadsheets. This type of data, after all, plays an important role in how we make sense of the world.

So I spent Monday’s district-mandated collaboration time working on my chart with my teammates. Jumping between my internet browser and Excel, I exported data, color-coded cells to match arbitrary cut scores, and designated which students fit into which subgroups. (When it comes to subgroups, my district uses a fairly common quartet of SWD [students with disabilities], LEP [limited English proficiency], African American, and Hispanic.) The end result looked like this:

To preserve anonymity, every number and X placement on this chart is a complete fabrication.

Crude, but functional. Data charts are seductive. By distilling complex relational forces into “stoplight data,” this scheme offers an illusion of efficiency, a color-coded roadmap that reveals little and obfuscates much.

Regardless of how much critical pedagogy I expose myself to, this sort of testing data makes my inner technocrat drool. It flattens and compresses and whispers in the language of knowable outcomes and cause/effect relationships. Charts of this type proliferate throughout every level of education. This is understandable; the intense bureaucratization of mass scale schooling requires a high level of data transferability.

The data is a few weeks old and relatively meaningless from an instructional standpoint. Even if students just completed the benchmark yesterday, the results from a quarterly exam designed by someone I don’t know covering an arbitrarily circumscribed section of the curriculum using a handful of multiple-choice questions aren’t valuable to me.

The rationale behind making the charts is similarly uninspiring. Pick and choose from the word bank of modern education reform’s empty sloganeering: To maintain high standards for all and ensure that every child receives the support they need. To maximize teacher effectiveness and tailor instruction to suit a child’s needs. To close the achievement gap and provide an empowering snapshot of every student’s ability.

The data is also already accessible via my district’s contracted benchmark provider: PowerSchool Group LLC, a subsidiary of private equity firm Vista Equity Partners. The decision to require every teacher to transfer information from a website to a spreadsheet strikes me as confusing at best and Foucauldian at worst. Understand it is not my intention to scoff at these administrative demands, only to work through the ramifications of what I’m asked to do on a daily basis.

So what do I do? If I disagree with the data chart and the assumptions behind it, how should I proceed? In “So what do I do?” Paul Thomas describes a number of ways teachers can claim their professionalism and push back. Thomas suggests that teachers identify and evaluate their obligations with care. Brainstorm with colleagues authentic versions of inauthentic mandates. Cultivate communities of empowerment that build professional knowledge and leverage individual strengths. Expand your influence and engagement beyond the walls of the classroom to include parents, fellow educators, and community members.

By keeping one foot firmly planted in lived reality, the post’s seven suggestions illustrate David and Julie Gorlewski’s idea that “Critical educators must enact dual perspectives; they are simultaneously agents of the state and agents of change.” In the past, I would have simply crossed my arms, closed my door, and refused to make the charts. With the Gorlewski’s quote in mind, though, such willful abdication seems petulant.

In the four days it took to write this post, the data chart has come and gone. Additional action items have risen up to take their place. Ours can be a profession of ceaseless demands, a hydra. In the scheme of things this data chart is a minuscule blip. But the blips add up and form the very fabric of the profession.

I struggle to find the time and the energy to engage in the aforementioned suggestions. But I write these blog posts and use social media to expand my professional network and knowledge. For now, this is enough. For now, this is what I do.

*During the Progressive Era, superintendents and top-level administrators cast themselves as data-savvy technicians. By adopting the language of business and social efficiency, the new administrative progressives created an archetype of “effective school leader” that remains influential today. As a side note, this is one of the reasons I enjoy learning about education history. It helps me place administrative demands, and pretty much everything else, in a useful context.

Grades, Modernity, and the New Administrative Progressives

Jørn Utzon, factory proposal, CC license

Grades, Modernity, and the New Administrative Progressives

The 2016 NCTE conference was amazing. Even though I was able to attend sessions on a variety of topics, I spent the majority of my time discussing grades. I took part in a round-table discussion focused on removing grades from secondary English classrooms. Most of our talk centered around what to do after getting rid of grades, quizzes, and tests. What do you put in their place? How do you make sure kids stay motivated? What kind of feedback do you offer? These valuable questions have been taken up by minds far sharper than mine, and I advise you to check out any of the blogs, books, and professional resources devoted to such topics. That’s not what this post is going to be about.

Instead I’m going to write about the gut-level unease that trailed me for the duration of my time in Atlanta, Georgia. The feeling began to gnaw at me during the round-table when I didn’t know how to field questions about removing grades at the high school level. As the teachers around me were right to point out, it’s much easier to throw out the grade book in middle school (where I teach) than high school. For most middle school students, topics like financial aid, graduation requirements, and college admissions don’t have teeth.

As for me, the single letter my district requires me to enter into the gradebook at the end of each quarter has little bearing on the educational trajectory of my students. I have structured my class so as to spend the absolute bare minimum amount of time thinking about student grades and points and rubrics. This is a privilege afforded to me by a trusting administration and a welcoming school climate.

So I sat at the round-table feeling foolish. Unlike the other round-table participants I did not come prepared to discuss feedback mechanisms and mastery learning. Nor did I have advice on setting up a gradebook or handling the paper load. I chose to spend the weeks leading up to NCTE feverishly typing up pages of notes on the history of grades. I’m not particularly interested in talking about why grades don’t work. Don’t get me wrong, I love to sit around and bloviating about the negatives of grades. I just don’t think it’s necessarily the most important part of the larger conversation about grades and measurement.

We know that grades don’t work. External rewards undercut intrinsic motivation and create situations where students/humans will do the least amount of work possible for the maximum result. Grades aren’t particularly effective proxies for learning, either. They’re crude symbolic abstractions of a complex and non-linear process. There’s nothing new to this assertion; educators have been speaking out against grades since at least the Common School era during the mid nineteenth century.

What struck me most during the anti-grading conversations I participated in at the conference was the ever present allure of efficiency. Behind the discussions about proficiency scales and standards-based alternatives to traditional grades lurked the human (and, in our case, distinctly American) desire to quantify and fix and stratify. In my mind, the Rob Marzanos and John Franklin Bobbits of education have begun to blur.

In his influential book The One Best System: A History of American Urban Education, David Tyack details a new class of 20th century school reformers, a group he famously called the “administrative progressives.” Administrative progressives sought to centralize public education under a unified banner of social efficiency, scientific management, and mental measurement. The progressive designation had nothing to do with John Dewey. Instead, this new group of reformers saw themselves as mavericks, iconoclasts who would lead public education out of provincialism and old world traditions through modern science and technology.

While grading systems were common across schools in the early 1900s, they lacked any sort of standardization or uniformity. Some schools stuck to old-world grading methods (emphasizing individual competition, ranking, and behavior) while others favored a more modern approach (the belief that grades could provide objective data and distinguish between ‘classes of men’). Various titles, levels, and numerical systems jostled elbows, often times within the same district. As schooling became larger and more complex, schoolmen needed a universal metric of academic progress and intellect to link schools vertically and horizontally. By the 1950s the A – F system of grades the majority of us grew up with was well on its way to becoming the national standard.

Administrative progressives remain an important part of contemporary education. Top level administrators and superintendents continue to act as bureaucratic data-managers, technocrats expected to know more about managing inputs and outputs than instructing a classroom full of students. Appeals to the debunked factory model of education, a myth as potent now as it was one hundred years ago, fit right in with administrative progressivism: education is stuck and the key to progress lies in more efficient technologies of instruction.

I sometimes feel that current anti-grading rhetoric has much in common with the desires of the twentieth century administrative progressives. A cottage industry has sprouted up around alternatives to traditional grades. Much of the rhetoric behind proficiency scales and standards based grading seems to me to be taken from a Progressive Era playbook. The language of a proficiency scale provides more information than a letter or number, and standards based grading grounds a teacher’s judgments rooted in content objectives, but they still serve to reduce the complexity of learning into transferable terms. Such alternatives to traditional grading are, as a mentor of mine once commented, the best way of doing a bad thing.

So how can we get around them? What about high school where letter grades and GPAs play an essential role in admissions, graduation requirements, and financial aid? Or when students transfer between schools and counselors use report cards and test scores to make important decisions about class placement? Grades, and the national consensus of how an A differs from a B, are baked into every single layer of schooling. Parent meetings depend on grades, when basic assumptions of a child’s competency, intellect, and progress draw from letters and numbers. This isn’t anyone’s fault, and this post isn’t about pointing fingers. Because any teacher who removes grades must grapple with the institutional inertia behind traditional marks.

Mechanisms of grading, ranking, sorting, and transferring are essential to modernity. In Making the grade: a history of the A-F marking scheme, Jack Schneider and Ethan Hutt situate grading as “…a key technology of educational bureaucratization, a primary means of quantification, and the principal mechanism for sorting students.” Removing grades can disrupt and draw attention to this. In our rush to find alternatives to assigning grades, we should be wary of implementing systems with similar functions.

Some questions of education can be answered through assessment technology. Tracking student progress and content mastery, for instance, benefit from any sort of standardized scale. More important questions of education, such as the what, the why, and the how, cannot be. We shortchange education discourse when the majority of our conversations stick to the former at the expense of the latter.

Pulling an Iceberg up a Mountain: A Portfolio Analogy

On November 3, 2015 I published my first blog post about classroom portfolios. Since then I’ve published three additional posts on the subject. This post is the first in a short series exploring my most recent attempt at portfolios.

I left school feeling hollowed out. I had just spent the entire teacher work day eyeballs deep in my students’ quarter one portfolios, and I wasn’t sure how I felt about what I’d seen. Some kids took the project and ran with it, penning reflections of surprising depth and complexity. A handful of students only had a slide or two to their name. The rest of the portfolios, as can be expected, landed somewhere between the two.

In theory, portfolios sound easy. Students select their best work and then write about it. By the time the end of the quarter rolls around, students have already done most of the heavy lifting. They’re not writing new pieces; all that’s left is to reflect. Yet portfolios are hands down the most stressful assignment I give. The final two weeks of every quarter, the time I typically reserve for students to gather and reflect upon their work, never fail to leave me gasping for air, covered in checklists and sifting through sticky notes.

This is because I find everything about the portfolio process to be incredibly complex and demanding. No matter how methodically I plan, every class is off script by the end of the second day.

All children, like adults, work at various speeds. Depending on factors like mood, diet, the day’s events, amount of sleep, interest level, home life, etc., a seventh grader can take anywhere from fifteen seconds to four minutes to follow through on a relatively straight forward instruction such as “Please take out your iPads, open up Google Classroom, and click on link at the top of the page titled Q1 Portfolio.” Knowing this, I start out small. Students insert pictures of already completed memoirs and title a few slides. But after a few days the requirements of the portfolio bloom, requiring students to make decisions about content, revise their work, evaluate their progress and, ultimately, argue for a grade. A matryoshka assessment.

No matter how many different ways I try to scaffold the process and dole it out in manageable chunks, some students become overwhelmed. As a result, the final days of portfolio creation are hectic. I’ll set the kids to a task, and then spend the duration of the class caroming from one child to the next, making snap decisions about how each student can finish the cumulative assignment under deadline while still trying to make it useful for them.

I have yet to think of an adequate analogy for the portfolio process. During this last round I felt like I was pushing an iceberg up a steep incline on a hot day. In this analogy my goal is to get as much water up the hill and across the finish line (the last day of the quarter) as possible. Before I start the climb I have everything under control. The iceberg is in one piece and the crisp air at the bottom of the hill keeps it from melting. Plans are made and positions are ready.

And then I begin to pull.

The sun comes out and the iceberg starts to melt. Chunks of frozen liquid begin to break off. Because I don’t want to lose any of the water to evaporation, I stop climbing and collect the fragments of ice into plastic zip-lock baggies that I tie around my belt. I have to do this quickly, because time is running and the iceberg is melting.

This pattern continues for the duration of the portfolio process. Knowing when to stop pushing the dwindling chunk in order to collect the pieces that have fallen off becomes agonizingly difficult. By the end of the ordeal I’m scrambling up and down the path, picking up hunks of ice hurling them in the general direction of the finish line.

The analogy isn’t air-tight, but you get the idea.

Portfolios can also lay bare the realities of teaching and learning. For instance this quarter I spent hours working with children individually and in small groups on memoirs. We took them apart, identified the genre’s components, and figured out how the pieces fit together. I employed a diverse array of instructional techniques and modalities in an attempt to help students understand themselves, their pasts, and their identities through language. To do all of this and then have a student write “I didn’t learn anything. I wrote a memoir in fifth grade” can be a humbling experience. I’m not disparaging my students or my own pedagogy, just trying to make sense of teaching, learning, and assessment.

Because reading portfolios is the equivalent of a masterclass in what it means to be a student in your class forty-five minutes a day, five days a week, nine weeks a quarter. It is an invaluable picture of what goes on inside your room. Don’t misunderstand me; I think that student-driven portfolios are a wonderful tool for self-reflection and growth. Powerful things can happen when students have the opportunity to go take stock of what they’ve achieved over nine weeks of study. I just have a long way to go in implementing them.

The next couple posts will be devoted to ‘thin-slicing’ the major components of our Q1 portfolio process. I’m eager to try and make sense of what my students created, and hopeful that the results will help me refine what has become a central component of my class.

The Head, the Heart, and the Hands: Our New Approach to Classroom Portfolios

Background

When I started using portfolio assessments last year (instead of grades and tests) I relied on the classic four language domains: reading, writing, speaking, listening. Students would select an artifact representing their work in each category. The first semester of this year I decided to eschew categories in favor of analogies. While I (and the students) enjoyed the analogies, I felt the portfolio was missing its core (or, to use Elbowian language, a center of gravity). I wanted our Quarter 3 Portfolio to include some new categories. I decided to focus on the body, specifically the work done by the head, the heart, and the hands. This post provides an overview of our process and how it worked out. And, as with every assignment, there is real value in doing this with the students.

Categories and Artifacts

For the head, students listed words like think, analyze, problem solve, decide, and compare. They said the heart might feel joy, sorrow, exhaustion, excitement, anxiety, and hope. And lastly they explained that their hands wrote, erased, tapped on screens, colored, flipped pages, put up sticky notes, and folded.

Students then had to pick the word that best described the quarter for each part. For instance, a student who did a lot of analysis might go with ‘analyze.’ Once students had their words down, they selected an artifact (something we did in class during the quarter) that best represented that word. That student who chose ‘analyze’ might go with a Flash Fiction draft that required him to analyze the components of the genre to make sure his piece was authentic.

One Organizer to Rule Them All

First quarter I provided too little in the way of guidance. Determined not to make the same mistake second quarter I ended up going too hard in the other direction. Students told me they were overwhelmed by the organizers. For the third quarter I tried to create a simple organizer that contained almost everything a student would need. Each column had the same instructions in it, but I slightly altered the font for each artifact to try and help the eye differentiate. The directions moved left to right. So whenever a student was done with a particular box they could draw a giant X through it. This helped them understand the sequence as well as provide a visual cue for progress.

At this point students wrote in their word and artifact on the left-hand side and completed the first square for each category.

Improving Our Artifact Reflections

Without proper planning, portfolios can become nothing more than a summative task, a way for students to show off what they’ve achieved over a semester. While there’s certainly nothing wrong with this, there isn’t much in the way of ‘learning’ going on when someone is merely putting on an exhibit. I find there’s value in helping students take the time to thoroughly process each artifact they choose.

I wanted to improve the reflection process this quarter. Using Starr Sackstein’s blog about teaching reflections (and receiving valuable feedback from Jana Maiuri), I settled on a sequence of activities to help students figure out ‘what should a great reflection include?’ Asking students to play a central role in selecting criteria for an assignment is a common and effective strategy. Students completed gallery walk, taking notes on various reflections posted around the room. What made each one effective? We took our time answering guiding questions on various pieces of chart paper and voting as a team on the most valuable components of a reflection.

I took the most popular results (using my professional judgment to add or remove anything) and typed them up. Students spent a little time trying out different brainstorming strategies before inserting their artifact reflections into their Google Slides portfolio template. Here’s what students ended up using to drive the content and form of their reflections:

Grade Evaluation Essay

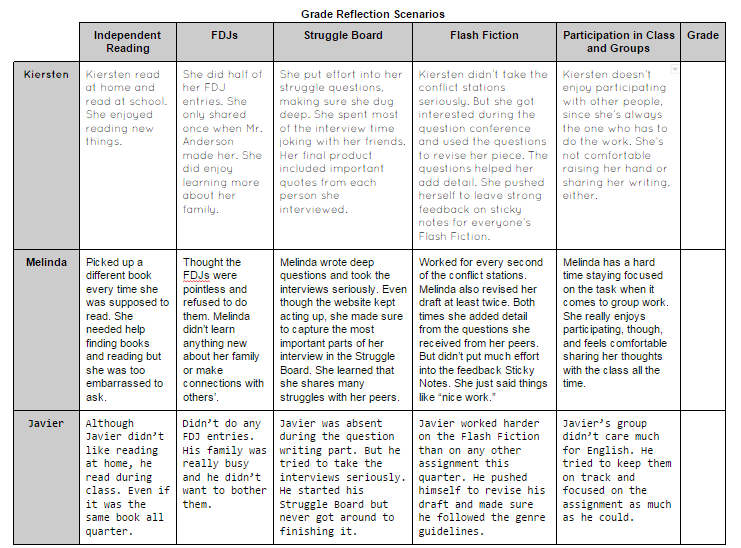

This is the final major component of the portfolio. As I’ve mentioned many times, I do not assign grades, quizzes, or tests in my classroom. My district, like most, still requires me to input a letter grade for each student at the end of the quarter. The Grade Evaluation Essay is my compromise. In order to try and help students grapple with synthesizing an entire quarter’s worth of work into one letter and one small essay, I created three scenarios. Although I haven’t used this lesson yet (that happens the next two days), I wanted to share my process. Individually and in groups students must read the following scenarios and decide A) what grade each of the fictional students ‘deserves’ and B) what factors/criteria/categories will be used to arrive at that grade.

Each student is a composite of popular behaviors and typical classroom occurrences. The items along the top are the major assignments of the quarter. My goal was to create scenarios without a clear “first, second, third” ranking. Kiersten, Melinda, and Javier all have strengths and weaknesses. By working as a group, students should be able to better leverage each other and bring multiple perspectives to bear on what is a complex task. Without cooperative learning, this task would be outside the Zone of Proximal Development for many of my students.

After trying to come to a consensus (regardless of outcome), we’ll write out each group’s grading factors. On the reverse side of the page is the same organizer sans writing. Each student will then use a few of the factors to brainstorm their own journey through each of the assignments. Finally they will turn their brainstorming into their final Grade Reflection Essay. The idea here is that the brainstorming page will move them left to right, from evidence to final statement. I haven’t written my own Grade Reflection Essay yet, but I’m excited to open myself up to students in a new way.

Preliminary Conclusion

The reflections look better than previous quarters. They’re more focused on specific learning and discovery. I’m excited to see how the Grade Reflection Essays turn out. If I stick with the corporeal theme next quarter, I’ll probably substitute ‘hands’ for ‘mouth.’ I’ll also do a better job trying in the body parts to the reflections. Ending up with a grade goes against much of what I believe in, but knowing when and where to compromise is key. I’ll look to update this post after the full results come in. Lastly, along with the two aforementioned educators, I’d like to thank Mr. Carter (my team’s excellent math teacher) for providing valuable feedback along the way.

Cook for 17 Minutes at 350 Degrees: Some Thoughts on Teaching Skills in the English Class Room

I’ve hit another snag in my development as a teacher. It’s one of those moments that seems to happen every couple months or so. I’ll be moving along in the classroom just fine until being hit in the face by an internal error, some conflict of values. It could be an assignment, a particular student, or a conversation with an admin. When you’re as mercurial and highly susceptible to mini revelations as I am (I claim that a book or person has ‘changed my life’ with startling regularity), you might think I’d get used to mentally lurching between ideological flashpoints. But I haven’t.

Each time it’s like walking into a pedagogical house of mirrors. I’m surrounded by so many different reflections of myself as an educator that I don’t know which is the ‘real’ me. It’s not that any one reflection is right; it’s that I’m trying to find the reflection that feels authentic and true in this moment. The newest version of myself that I can project into and grow into. The pattern is always the same. Some inchoate sense of unease begins tingling my nerve endings. The discomfort remains ever shifting in my periphery, lurking in the background until I’m able to finally put a name to it. This post is my attempt to name it. I’m currently residing in a liminal space regarding academic skills. I’ve known for some time that I’d have to come to a decision about the role of academic skills in my classroom.

My wife and I decided to heat up a frozen pizza for dinner last night. As my eyes scanned the colorful box for the temperature and cooking time, a thought occurred to me. This task, looking over a ‘real world’ nonfiction text (a pizza box) in order to locate a particular piece of information, is similar to what we have students do when we ask them to work on identifying and analyzing organizational patterns. For those of you unfamiliar with middle school English Language Arts standards, organizational patterns are the common ways authors organize information. Compare and contrast, cause and effect, chronological order, etc.

After finding the information I needed, I reflected back on my process. I realized that my quest for information, a real desire rooted in a biological need, did not hew to any particular strategy or pattern. I neither read nor reread. I didn’t look for signal words or analyze text features (bold letters, text boxes, images). The only heuristic I put into place was whether or not the visual information coming in took the representational form of a number or a letter. More specifically, I’m pretty sure I simply inserted a lazy gestalt filter that highlighted any appearance of a two or three-digit number (350 degrees, 17 minutes).

Organizational patterns were sitting on my brain. They were the most heavily tested skills on my student’s most recent benchmark exam (My district’s benchmark exams are created and tracked by Interactive Achievement, a Virginia company purchased last year by PowerSchool Group. PowerSchool Group, in turn, was purchased by Pearson back in 2006 only to be sold to Vista Equity Partners, a private equity firm, in 2015). I couldn’t help but wonder about the value of devoting time to teaching organizational patterns as a skill. In short, what was the point?

As an English teacher, I’ve joined colleagues in discussing the importance of students learning about main idea, the difference between summarizing and paraphrasing, and Greek and Latin roots and affixes. The reasons behind students learning these things are the usual suspects: college and career readiness, the ‘real world.’ I’m not saying these aren’t skills. I’m just not sure about their value. I’m also questioning the need to elevate these skills as the primary point of focus for my classroom.

As a student of history, I know that curriculum is a political construction rooted in particular ideologies and value systems. I also know that the economic purpose of education, a vision of schooling rooted in producing market agents equipped with the skills deemed necessary to compete in a particular workplace, now functions at a hegemonic level. Focusing on these skills and standards limits what I can do in my classroom to a narrow and superficial spectrum. Any talk of difference, of plurality, of building a collective of community-based individuals is silenced and labeled superfluous. Because those things can’t be tested, and the machinery of data requires testable skills.

But when I receive back low test scores a real sense of panic sets in. The dizzying artifice surrounding the act of testing makes it almost impossible to treat test scores as anything other than capital T Truth. Those moments of moral and ethical panic are visceral. The urge to commit myself to the language of the technocrat, of skill matrices and action plans, is staggering in its strength. To try and discuss larger, thornier questions of purpose and pedagogy is to relinquish the thoroughly modern idea that teaching means testing, standardizing, and recording.

I have to question the point of spending valuable classroom time asking children to work on these things. I rarely draw on these discrete mechanisms, and I work in education. I barely understand most of the things I do on any given day. I write and read and try to do the most amount of good for the most amount of people with the limited influence I’m gratefully allowed to wield.

I’m not sure what I’m going to do moving forward. I just know that I must press forward and reach some sort of conclusion for myself. I’m acutely aware of my pedagogical failings, and I feel genuine sorrow for the children I teach who might be academically stunted by their 7th grade English teacher’s misguided quest to align spirit with practice. Until I’m able to articulate my personal vision of the language arts classroom, I must trust myself to enact a pedagogy of kindness and respect, even if that means some time away from standards and measurable skills.